Trump Took Credit for Stock Market Records. Does He Deserve Blame for the Plunge?

The decline over the past few months, particularly since the start of December, is the Trump Slump.

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Green means up and red means down in the stock market. Lately there have been many red days. But the true color of today’s market is golden orange—the hue of the pompadour atop the head of President Donald Trump. Because for better and for worse, this has become Trump’s stock market. Until October, the extended bull market was reasonably called the Trump Bump. The decline over the past few months, particularly since the start of December, is the Trump Slump.

Few would dispute that Trump is a volatile personality who’s having a volatile presidency. He’s shaken the establishment to its roots. Yet for most of his time in office, volatility in the stock market was below its long-term average, with the exception of a spell in February and March. Investors’ calm always seemed a bit out of step with reality. But fluctuations do tend to increase when prices are trending down, and that’s exactly what happened in 2018’s fourth quarter. The Chicago Board Options Exchange Volatility Index hit 36 the day before Christmas, up from below 15 in the summer and early fall.

America finally has a stock market to match the man in the Oval Office.

One question to ask at this point in the turmoil is how much Trump has affected the stock market—for better during the bump and for worse during the slump. The opposite question is how much the worst year for stocks since 2008 has affected Trump. Will the market rout chasten him, cause him to retreat from some of the policies and language that have sent markets into a tizzy? Or will it drive him to attack the status quo even more ferociously to prove himself right and recapture some of that bull-market magic?

The conventional wisdom among economists is that presidents get too much credit and blame for the ups and downs of stock indexes. They are, it is said, like a mahout astride an elephant that goes wherever it wants to. This makes some sense. The fact that stocks have done better on average under Democratic presidents than Republican ones (back to Herbert Hoover) isn’t proof Democrats have a special touch for equities.

But there are times when presidents do matter, a lot, and this is one of them. The Trump tax cuts passed one year ago are an example. They directly benefited the stock market by boosting companies’ after-tax profits, which of course underpin stock valuations. Trump’s deregulation agenda also boosted stock prices. The federal government published fewer than 20 “economically significant” regulations in 2017, down from close to 100 in 2016 and the least since the beginning of the Reagan administration, according to George Washington University’s Regulatory Studies Center.

Some might argue that it was a mistake to cut corporate taxes at a time of soaring deficits, or to ax regulations intended to protect the public’s health and safety. But the changes clearly did help the stockholder class by lifting share prices. They also helped smaller companies that aren’t publicly traded. “The president has been more aggressive than any previous president we can remember in creating a good environment for people who run their own businesses,” says Jack Mozloom, senior vice president for public affairs at the Job Creators Network, a Dallas-based small-business advocacy group.

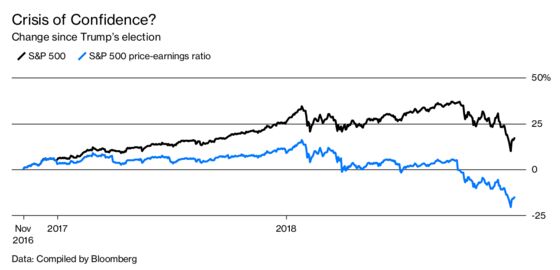

Those Democrats who hate to credit Trump for anything positive are loath to admit that the stock market’s upward march had anything to do with him, preferring to attribute the rise to his predecessor or the Federal Reserve or just plain luck. But it’s hard to ignore that stocks jumped in the days after his surprise election and continued to gain ground for almost two years. That’s the Trump Bump.

There’s even a theory as to why volatility remained low despite the Trump chaos: It’s that investors couldn’t read the confusing signals from Washington, so they ignored them. “One day NATO is obsolete, another day it is not. One day China is a currency manipulator, another day it is not,” financial economists Lubos Pastor and Pietro Veronesi of the University of Chicago Booth School of Business wrote in May 2017 for VoxEU.org, a website of the Centre for Economic Policy Research. “Markets continue listening to politicians, but they pay less attention than they used to.”

Sometime around the start of October, though, something soured for stocks. The question is what—and who’s to blame. After the failed Bay of Pigs invasion, a rueful President John F. Kennedy said, “Victory has a thousand fathers; defeat is an orphan.” Trump has turned JFK’s expression on its head. In a string of exultant tweets he took credit for the bull market; now that stocks are falling, he’s tried to pin the decline’s parentage on others, including Democrats (for pushing the Russia investigation) and Jerome Powell, his choice to chair the Federal Reserve.

There’s something to be said for Trump’s defense. It’s true that the Powell Fed isn’t doing stocks any favors. Investors really don’t like rising interest rates. The Meltdown Before Christmas came on the heels of a Dec. 19 statement from the Federal Open Market Committee that skated past the market’s weakness, cited “strong” economic growth, and said “some further gradual increases” in rates would likely be necessary.

But that shouldn’t let Trump off the hook. While markets, like wayward elephants, do tend to have minds of their own, it’s also possible to identify specific ways in which Trump has contributed to the downturn. His prosecution of the trade war with China, in particular, has rattled investors. The 90-day truce between the two nations, agreed upon at the Group of 20 summit in Buenos Aires on Dec. 1, has done little to buoy the stock market because investors realize that hostilities could erupt again when the cease-fire ends in March. The S&P 500 price-earnings ratio has fallen 13 percent since September. Trump, in general, was the No. 1 thing keeping institutional investors awake at night in a mid-December survey by investment bank RBC Capital Markets.

The S&P 500 fell 2 percent in early trading on Jan. 3 after a weak reading on U.S. manufacturing and a cut in projected revenue by Apple Inc. Apple Chief Executive Officer Tim Cook cited weakness in China, which he said was exacerbated by trade tensions with the U.S. Apple stock closed the day at 142.19 down almost 10 percent.

Trump’s Twitter attacks on Powell could also be backfiring. Even some market analysts who think the Fed should back off from raising interest rates say that the president’s messaging could induce Powell to demonstrate his independence by forging ahead with unnecessary hikes. Or, for bond investors worried that the Fed will accede to the president, there’s an expectation of accelerating inflation. That would cause bond prices to fall—which generally causes stock prices to fall as well.

Trump’s leadership style is also wearing poorly. His strategy of keeping people guessing and off balance might work well with adversaries, but it alienates friends. “I’m not aware of another U.S. president trying to weaponize uncertainty. And for good reason: It harms American interests as well as foreign ones,” says Steven Davis, a professor at Booth who helped develop an economic policy uncertainty index. (The news-based version of the uncertainty index is just below the top 10th of its 34-year range of values.)

It’s true that the stock market isn’t the best metric for judging a president. Stocks can go up even if the president is performing badly and down even if he’s doing well. For example, just because getting tough on China is bad for some tech stocks doesn’t mean it’s the wrong thing to do. Conversely, many of the things that are most troublesome about Trump don’t show up in stock indexes—the coarsening of the public discourse, the damage to America’s global alliances. And some potentially harmful actions, such as trying to weaken rules on mercury emissions from coal plants, could boost certain stocks.

Still, there’s rough justice in calling out the president for the stock market’s decline, simply because he so often cited its rise as evidence of his success. A sample from 3:04 a.m. on Dec. 19, 2017: “DOW RISES 5000 POINTS ON THE YEAR FOR THE FIRST TIME EVER - MAKE AMERICA GREAT AGAIN!” “He definitely believes it’s a measure of how he is doing and how his policies are performing,” Corey Lewandowski, Trump’s former campaign manager, said in an interview at a Trump Hotel book party on Dec. 11.

At times, Trump seems to be using presidential announcements to goose the market. Stocks rose on Dec. 31, for example, after a weekend tweet in which he said that a phone call with Chinese President Xi Jinping on trade had gone well. But that tactic goes only so far: Investors can react badly if reality doesn’t match expectations. Even some of Trump’s biggest supporters see his boasting as an error. “If you’re going to tie yourself to the stock market, you’re going to go down when it goes down,” says Mozloom, the small-business advocate. “As a political matter, he should have anticipated this.”

What Trump does next may depend on what the stock market does next. If it recovers swiftly from what he called, on Jan. 2, a “little glitch,” this episode will be forgotten like a bad dream. But what if the market goes down further or simply bumps along at this lower level? One theory is that this would strengthen the hand of some of Trump’s more moderate advisers, who have frequently tried to steer him away from extreme actions by warning of negative market reactions. The president appears to have more respect for the judgment of the market than for the advice of academics and pundits. Then again, Street cred didn’t help Gary Cohn, Trump’s former chief economic adviser, when he tried to stop Trump from imposing high tariffs on steel and aluminum imports. The showdown over the tariffs led to his resignation in March (upon which stocks duly fell).

Now it’s Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin who’s in the hot seat. One sign that he knows he’s vulnerable is his desperate attempt to buoy stock prices by issuing a statement the Sunday before Christmas saying the nation’s six biggest banks had “ample liquidity” for lending. That’s the kind of reassurance that’s usually reserved for a crisis. Trump expressed confidence in Mnuchin after that episode, calling him talented and smart, but such reassurances have had short shelf lives.

There’s a scene in the movie Lost in America in which Albert Brooks finds his wife, played by Julie Hagerty, at a roulette wheel in Las Vegas, having gambled away the family’s nest egg, maniacally repeating, “Come on 22!” For Trump, the equivalent would be doubling down on harmful policies in the belief—or desperate hope—that eventually they will work. The further the stock market falls, the greater the temptation to do something drastic to get back in the black. In game theory, this is known as gambling for resurrection.

Trump is a long way from that scenario. After all, the market is still up since his election. But he is shedding the advisers—like Cohn, former Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, and former Defense Secretary James Mattis—who tried to keep him from indulging in his darkest impulses. Meanwhile, a partial government shutdown drags on, the Mueller probe seems to be coming to a head, and Democrats are ready to hound him as they take control of the House of Representatives.

The Trump Slump is a bigger phenomenon than just a downturn in the stock market. But every red day on Wall Street is another punch to the president’s gut. —With Joshua Green and Shawn Donnan

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Howard Chua-Eoan at hchuaeoan@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.