How a Beloved Vegetarian Restaurant Is Doing Better Than Ever, Despite Everything

How a Beloved Vegetarian Restaurant Is Doing Better Than Ever, Despite Everything

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- The outdoor dining shed in front of Dirt Candy, one of New York City’s best vegetarian restaurants, has been mostly empty since November. After relying on the structure to get through the pandemic to that point, Amanda Cohen, the restaurant’s chef and owner, decided to stop serving food outside. She briefly entertained the idea of continuing to use the shed to serve drinks. Then the weather got cold, and nobody seemed interested in shivering over a $17 mezcal with cucumber. “Outside bar is not a thing,” she texted me a week into the experiment. She noted that a passerby carrying his own beer had sat and made himself at home. Here, at least, was a satisfied guest—even if he wasn’t, in the formal sense, a customer.

Even so, Cohen couldn’t bring herself to tear the shed down. “What if we get a fourth, fifth wave? I’ve lost count,” she said. In December, as if on cue, omicron appeared, and a few people started taking those drinks outside after all.

Alfresco dining had never been in Cohen’s long-term plan. “This is not as nice as our dining room, and I can never make it as nice,” she’d told me in early June, as we sat at an outdoor table during a lunch rush. I’d just completed my vaccination regimen and was planning a summer-long restaurant binge. I also wanted to understand what recovery in the restaurant industry might look like, especially for someone such as Cohen, a chef with an extensive history of making unique food and speaking her mind on business matters.

It was a beautiful day on the Lower East Side, sunny but cool, and the city still seemed to be floating on the feeling that we might really be nearing the pandemic’s end. The day prior, New York’s then-governor, Andrew Cuomo, had lifted most Covid-19 restrictions. “Delta” at the time still primarily meant the airline, and people were having entire conversations without mentioning the supply chain. Cohen told me she expected to remove the shed by September, a time far enough in the future, it seemed to us, that Covid would likely have run its course.

The outdoor space had its charms, despite Cohen’s misgivings. The three-sided enclosure made of wooden slats was lined with plants and flowers, illuminated by white pendant lights in the evenings. But it was loud. Cohen’s voice disappeared for a few sentences when a bulldozer crawled by, then again when a truck stopped to unload supplies. The shed had already been clipped twice by city buses, though neither accident had caused much damage.

There were other drawbacks, namely the challenge of transporting plates of carrot gnocchi, which Cohen prepares floating in pesto sauce, past the joggers, stroller pilots, and joint smokers sharing the sidewalk with Dirt Candy’s servers. “It’s a long way to carry something that has a broth that’s maybe sloshy,” she said. “Our food’s pretty finicky.”

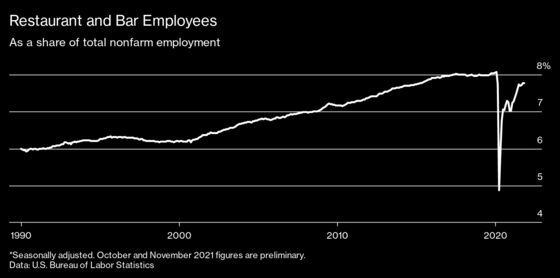

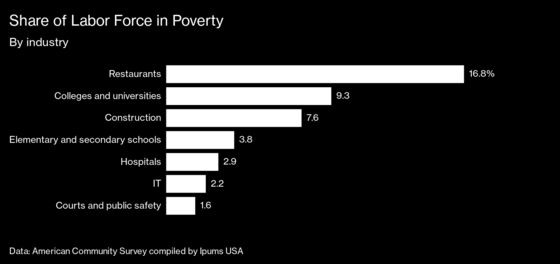

Cohen understood these were good problems to have; Dirt Candy had been lucky to survive at all. Some 90,000 food and drinking establishments in the U.S. closed during the first 13 months of the pandemic, according to the National Restaurant Association. This was a crushing blow to a major economic sector that has yet to fully recover. Dine-in visits to restaurants in the 12 months ended in September were down 48% from the same period ended in September 2019, according to research from NPD Group Inc. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics counted 11.6 million jobs in the industry in November, 756,600 fewer than before Covid.

For Cohen and restaurateurs like her, surviving the pandemic meant making once-unimaginable compromises. She was forced to lay off almost all of her staff. She offered delivery (then gave up on it), built the shed (then pretty much gave up on that, too), navigated massive new government aid programs, and raised prices and wages. In the process, she reexamined almost every part of her operation.

The experience was brutal, a case study in entrepreneurial adaptation during a crisis. It was also a revelation. There have been points during the pandemic when Cohen considered closing altogether, but eventually, slowly, the business started working. The late-2021 version of Dirt Candy is more profitable than it’s been at any point in its 13-year history, she says, suggesting that the future for restaurants—at least some restaurants—might not be as grim as conventional wisdom would suggest. “I know numbers aren’t magic, right?” Cohen says. “But this feels a little magical.”

Vegetarians can object to the reputation all we want, but the general view of meatless cuisine is that it’s joyless and generally attracts only those willing to tolerate a steady diet of lentils because we care about the feelings of pigs, because it’s cheaper, or because we simply like to lord it over people. Cohen, who isn’t a strict vegetarian herself, had something else in mind when she started Dirt Candy: a restaurant based on the idea that the cuisine’s limitations offered opportunities for humor and even swagger. Dirt Candy has served “hot dogs” made of smoked broccoli, cauliflower florets that look like chicken wings, and other whimsical dishes. “Anyone can cook meat,” Cohen boasts on the restaurant’s website. “Leave the vegetables to the professionals.”

In another unique twist on plant-based fare, Cohen decided she could charge real money for it. Dirt Candy’s current tasting menu, consisting of five small courses—the most substantial of which would be unlikely to register as a main at many restaurants—costs $85 per person, including a service fee in lieu of tip, but not drinks or tax. This made the timing of her restaurant’s start less than ideal. Dirt Candy opened in October 2008, a month after the stock market crash that helped kick off the Great Recession, and there were nights when Cohen served fewer than a dozen people.

But her cooking slowly gained a following. Within a few years she’d been featured on Iron Chef America, the Food Network competition show; had written a well-regarded cookbook; and was earning praise from critics. In a 2012 review titled “Like a Kid in a Vegetable Store,” Pete Wells of the New York Times marveled at how Cohen had invited people to “see vegetables as an indulgence, a pleasure that is not quite guilty but not entirely innocent, either.”

The fame wasn’t immediately followed by fortune. Like many restaurants, Dirt Candy saw its profits hover around nonexistent, and Cohen regularly paid the bills by taking consulting and other side gigs. Part of the problem, despite her protestations that vegetarian food doesn’t have to taste like health food, was that the restaurant attracted a crowd less likely to indulge in the kind of drinking that helps pad the margins. “Some nights it’s a sea of waters,” she admits. “It sort of breaks your heart.” Diners also expected to pay less for vegetables than they’d pay for meat, even though many of Cohen’s costs—rent, wages, sales tax—were comparable.

She made it even harder on herself by becoming one of the first prominent restaurateurs to eliminate tipping. When Dirt Candy moved to a larger, fancier location in 2015, she raised menu prices to include a 20% “administrative fee,” hiked hourly wages to at least $18 an hour, and stopped accepting tips. Later the same year, Danny Meyer, Tom Colicchio, and other high-profile restaurateurs also began experimenting with replacing gratuities with set service fees.

The innovation won Cohen and her peers praise from industry critics who’d long argued that tips compounded racial disparities and led to sexual harassment of servers, but there were drawbacks. Not only did the policy make Dirt Candy seem more expensive, but it also increased its revenue and payroll. This meant higher bills for sales tax and insurance for workers’ compensation and unemployment. Cohen and the other restaurant owners had hoped to inspire a broader movement, changing diner expectations and spurring regulatory changes that would motivate the industry to compensate workers fully. The idea didn’t catch on, though, and some of its famous pioneers, including Meyer and Colicchio, backtracked.

Cohen stuck with it, a decision that came with one unexpected upside: By paying high wages, Dirt Candy set its employees up to get larger unemployment checks if they lost their jobs. That’s what happened in March 2020 to almost all of them.

Dirt Candy served its final pre-pandemic meal on Saturday, March 14, 2020. Before it was set to reopen the following week, the state imposed a sweeping lockdown. Cohen and her managers told everyone they’d be shutting down for at least two weeks and most of the staff would be furloughed. She had a cushion of about $90,000 in the bank, but even with drastically reduced labor costs, many of the restaurant’s expenses didn’t go away. “We didn’t turn off the walk-in,” she says, meaning the giant refrigerator. “I still had to pay my landlord. I didn’t pay him the full rent, but I still paid a lot. I still had to pay sales tax for March.”

Cohen kept the managers on staff, along with a dishwasher she paid to come and clean once a week. In July she partially reopened with a skeleton crew of six, down from 35. By that time, she says, Dirt Candy had only $20,000 in operating capital left. But she’d also secured the first of two federal Paycheck Protection Program loans; combined, they totaled $636,000. (The debt is likely to be fully forgiven.) She expected to lose money most days, but the government aid would allow her to run at a loss, and she figured it was worth it to remind people the restaurant existed and to give herself and what was left of her staff something to do every day. The workers she’d let go had to get by on unemployment, along with a promise of a job offer if and when things returned to normal.

This version of Dirt Candy was significantly different from its former incarnation. Cohen designed a to-go menu featuring more portable foods, such as mustard-fried tofu buns and spinach croque-monsieur. She set up a few picnic tables with umbrellas outside. The transformation wasn’t particularly successful. “We’re not a neighborhood restaurant, so people wouldn’t think of just stopping in for a quick meal or a sandwich,” she says. “It takes a really long time to change people’s impressions of you.” The first day the new Dirt Candy was open, sales totaled $200.

Some restaurants found success replacing parts of their traditional operations with takeout, meal kits, or online cooking classes. Dirt Candy wasn’t among them. As Cohen told the foodie website Eater, the $14 vegetarian croque-monsieur resulted in a 90¢ profit—but only if a diner took the sandwich on a plate and ate it outside. If the meal was ordered to go, the added cost of a compostable container meant she lost 80¢. (She couldn’t bring herself to use cheaper ones.) The numbers were even worse for delivery: Cohen lost as much as $3 for every sandwich delivered through DoorDash and Grubhub because of fees.

Dirt Candy’s business did start to recover, but new costs also started piling up. Once the weather cooled down, Cohen hired a local handyman to build the shed, a feature that had fast become necessary for any sit-down restaurant in New York. She hung lanterns and acquired a handful of space heaters. The shed needed electricity, which meant hiring a team of electricians, who spent four days running wires from the basement. After they flipped the switch, her power bill tripled. It peaked at about $6,000 a month that winter, even though the heaters were mostly warming up empty tables.

By May 2021, Cohen was ready to reopen her indoor dining room and resume some semblance of normal service. But she warned customers that the new Dirt Candy would be different. The restaurant had previously offered multiple tasting menus; now there was a single five-course option that cost 55% more than it did before. The pandemic had also opened Cohen’s eyes to how vulnerable her workers had become. So she began offering a minimum of $25 an hour, an increase of almost 40%, along with the option to buy into a company health insurance plan after three months—an unheard-of benefit in the industry. Even though this was a rare deal by restaurant standards, Dirt Candy didn’t have much luck luring back its former employees. Most people working in restaurants don’t plan to do so forever, and the pandemic meant staff would be exposed to a dangerous illness. Dirt Candy made the offer to everyone who’d been furloughed. Only two returned.

In late July, about six weeks after eating with Cohen in the shed, I returned to spend a day in Dirt Candy’s kitchen. Cohen sat at the counter, typing up a university dining hall menu as part of a consulting gig. I tagged along behind various kitchen staff, most of whom wore matching pink bandannas. Only one worker wasn’t yet vaccinated, according to Cohen, and almost no one wore masks, though the following week she decided to make everyone put them on.

My chaperone was Matt Miller, the daytime sous chef. Miller, a skinny, bearded guy—who, for reasons he explained but I didn’t fully grasp, has a tattoo of the Penguin Books logo on his forearm—was one of the few people who stayed on through the pandemic; his wife, Dirt Candy’s former pastry chef, runs the kitchen at Lekka Burger, a vegan burger joint Cohen started in 2019. A major part of Miller’s daily routine this summer was salt-roasting beets, a process that involves covering deep pans of the root vegetables completely in salt and cooking them for two hours. The salt forms a hard casing around the beets, which Miller then had to crack open, covering him in grit. “It’s not my most favorite thing to do,” he conceded. “I’m always feeling like I came back from the beach.”

By contrast, multiple members of the daytime staff told me they looked forward to removing the skins from hundreds of cherry tomatoes, a necessary step in making tomato leather tarts. Miller described the process as meditative. He showed me how to do it, and sure enough it took only a few tomatoes for me to work myself into a pleasant trancelike state.

This is more or less how prep shifts worked before the pandemic, but because Cohen was offering a single menu, she could predict almost with certainty the quantity of each ingredient she’d need. She could cut down on food waste and significantly reduce costs even as the per-unit price of many ingredients increased with inflation. The streamlined menu was also one of the reasons she could serve the same number of meals she did in 2019 with a staff that’s about 70% the size it was in the beforetimes—particularly important given the increased wages and benefits she was now offering.

Although Dirt Candy seemed to be headed in the right direction, the transition was still proving tricky. Cohen and her servers said it could be grueling to deal with customers who’d been housebound for so long they’d forgotten how to interact with people or with those who’d grown terrified of the unseen dangers that might be lurking on even the cleanest-looking forks.

Dirt Candy thrived through much of the summer, despite the arrival of the delta variant. Then in late August five staff members, all of them vaccinated, tested positive. Some temporarily lost their sense of taste and smell. Cohen had to shut down the restaurant for four days across a weekend, which meant she didn’t turn a profit that month. It also reinforced the feeling that Cohen’s springtime hope of being done with Covid wouldn’t be realized.

Instead, she was learning to exist within the pandemic. Friday, Dec. 3, was the single best night in Dirt Candy’s history. Not only did the tables fill up—new variant be damned—but Cohen said far more people than usual were splurging for wine pairings. “People are coming out,” she says. “And they want to spend money.”

My wife and I went to Dirt Candy for dinner one weeknight this fall. When Cohen came over to our table to drop off the cucumber caviar, she admitted she was dreading the prospect of another Covid winter. “If I have to put heaters back in that thing,” she said, indicating the dining shed, “I’m going to cry.”

Still, she was feeling optimistic. Her customers had come through the pandemic with money to spend and lots of nights out to catch up on. While Dirt Candy is largely a date restaurant, more people had been booking tables in groups of four or six, and Cohen was running through more than her usual supply of birthday candles. “We’re doing Friday night numbers every day of the week,” she said. Offering compensation that’s far more generous than market rates had also allowed Dirt Candy to mostly avoid the crippling labor shortages that other restaurants were experiencing.

Eating in a restaurant has changed, no doubt. There’s something distinctly unromantic about making a reservation online, then being forced to acknowledge a disclaimer stating you’ll need proof of vaccination and your dining experience must be limited to 90 minutes, then receiving a text message asking for an address to comply with contact-tracing requirements. Walking into a restaurant with a mask on isn’t the best way to start a date.

And yet, there are parts of the experience that just snap back into place. The dining room was mostly empty when my wife and I sat down. After Cohen came by with the first course, a food runner brought over the tomato leather tarts, skins expertly removed, and then the beet steaks. Everything was delicious, and it got noisier as the courses continued to come out one by one and people filtered in—couples on dates; a mom who’d come with a daughter about to go to college. At the end of our allotted hour and a half, our plates were cleared, and as we stood up, I looked around. Every table was full.

Read next: How Food Samaritans Help Supermarkets Reduce Waste

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.