The Pandemic Is a Bonanza for Malaysia’s Medical Glove Industry

The Pandemic Is a Bonanza for Malaysia’s Medical Glove Industry

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Well before the new coronavirus came to global attention at the end of January, Lim Wee Chai had a feeling his company was headed for a good year. Since he founded Top Glove Corp. Bhd., the world’s largest maker of medical gloves, in 1991, there’s been one constant: Pandemics are good for business. “SARS, H1N1, bird flu, swine flu—there was a big surge in orders and demand,” Lim says. So as reports of a mysterious virus began to emerge from China, “we prepared ourselves for a big thing.”

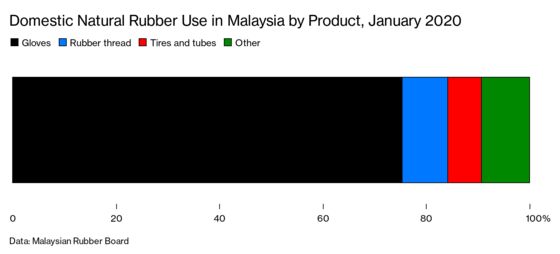

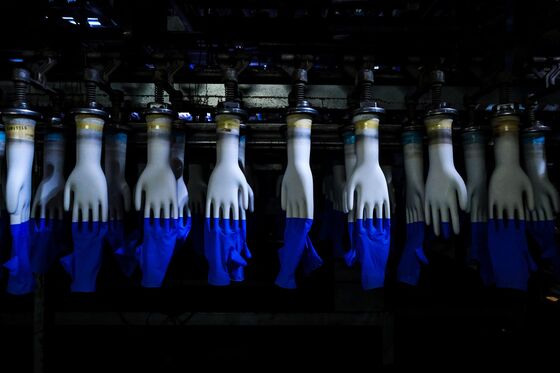

The same is true of Lim’s local rivals. Malaysia is the world’s largest source of medical gloves, with a market share of about 65%. Dozens of companies, most clustered in industrial cities near Kuala Lumpur, turn out over 200 billion “units”—single gloves—every year, destined for doctor’s offices and hospitals all over the world. The sector has grown steadily since the 1980s, in tandem with more stringent hygiene standards in the developed world and improving medical services in China, India, and other emerging economies.

What’s happening now, though, could make the previous expansion look modest. In 2019, Malaysia exported about 182 billion glove pieces, accounting for $4.31 billion in revenue; this year, according to the Malaysian Rubber Glove Manufacturers Association, the figure could go as high as 240 billion pieces. Expectations of a bonanza have made glove companies one of the few bright spots in the country’s economy, with investors driving up Top Glove’s shares almost 45% since the start of 2020. “I can guarantee you that every glove manufacturer in Malaysia today will expand,” says Denis Low, the association’s president.

Malaysia’s glove dominance can be traced to the 1980s, a period that some manufacturers refer to as the “big bang.” The trigger was the AIDS epidemic, which created a surge in demand for gloves for doctors, nurses, and other health-care workers and even for police in the U.S. and Europe. Western manufacturers couldn’t keep up, and Malaysian entrepreneurs, who benefited from lower labor costs, stepped in to fill the void. Although AIDS turned out to be less transmissible than initially feared, glove demand has largely held up, with Malaysia providing a rising proportion of the supply.

British colonists introduced rubber trees to what’s now Malaysia in the 1870s, and the plants—originally from Brazil—thrived in the country’s hot, humid climate, quickly becoming a major export industry. Rubber doesn’t command the same economic significance today, but Malaysia’s plantations still give glove manufacturers easy access to a crucial raw material: the drained sap better known as latex. Although so-called natural rubber gloves today make up less than half the market, in part because of concerns about allergic reactions, Malaysia’s large oil industry provides local glove manufacturers ample supplies of the petrochemicals needed to make synthetic ones.

The rise of Malaysian glove making hasn’t been without controversy. In 2018 The Guardian accused Top Glove and WRP Asia Pacific Sdn. Bhd., another large manufacturer, of mistreating migrant laborers by forcing them to work excessive hours, withholding pay, and confiscating passports. Britain’s National Health Service began an investigation of glove suppliers there, while the U.S. Department of Homeland Security blocked the importation of gloves made by WRP. Both companies have denied wrongdoing, and the U.S. lifted its ban on WRP in late March because “the company is no longer producing the rubber gloves under forced labor conditions,” U.S. Customs and Border Protection said in a statement.

The resulting scrutiny improved conditions somewhat for workers, who hail largely from Nepal and Bangladesh, “but there are still massive issues,” says Andy Hall, a British activist who’s studied the industry since 2014. And the urgent need for gloves generated by the coronavirus pandemic, he warns, could tempt governments to look the other way in response to abuses now and in the future. “We need to ramp up production, but the workers also need to be protected,” not least from the risk of contracting the virus themselves, Hall says. “It’s not either-or.”

Local glove companies are in an all-out race to crank out more product, even as most of Malaysia’s economy remains frozen. With more than 5,300 officially confirmed cases, the country has one of Southeast Asia’s more severe outbreaks, and a national lockdown began on March 18. During the first 12 days of those measures, glove factories were able to operate with only 50% of their workers. The industry has since received an exemption, although many suppliers and logistics partners remain at half strength.

At Top Glove, the crisis is necessitating other compromises. With international travel largely halted, it can’t hire new workers overseas and is trying to find local recruits to fill the gap as it boosts production. The company is using almost all its manufacturing capacity, and the lead time required to fill an order has climbed from 30 days to as long as 150.

The destinations of those orders reflect the progress of the pandemic—and where it may be flaring up next. Not surprisingly, the first spike in demand at Top Glove this year came from China, followed by South Korea, Hong Kong, and Singapore. Italy, Spain, and other European countries soon picked up, along with the U.S. And now? “Brazil,” Lim says. “The orders are coming up very strongly.”

Read more: Inside a Factory Racing to Supply America With Virus Test Swabs

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.