The Next Big Phones Could Bring a Billion People Online

The Next Big Phones Could Bring a Billion People Online

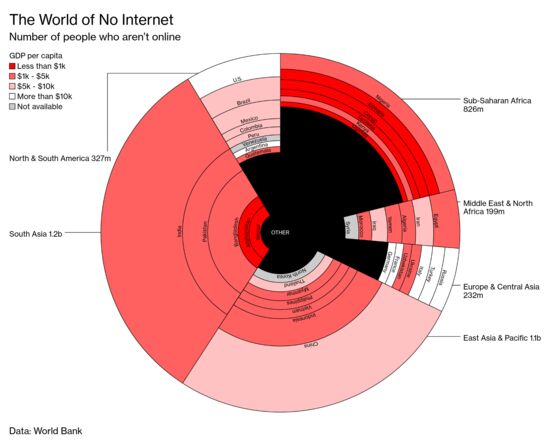

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- A few short years ago, the perennial corporate quest for the Next Billion Internet Users seemed like a strong pitch. Tech companies would put the sum of human knowledge in the pockets of the world’s poor, all while pulling in ad dollars from big multinationals that would pay to reach them. These days, though, the costs of this business model are clearer. Social media apps have been blamed for stoking a genocide in Myanmar, lynchings in India, and electoral interference around the world. They’ve also contributed to a creeping, grinding addiction to our glowing, rectangle-shaped dopamine drips. Do we really think the 50% of humanity without an internet connection would be better off with one?

Well, yeah. Greater internet access correlates directly with improved health care, education, gender equality, economic development, and lots of other goals well-financed nonprofits struggle to achieve. Boosting a poor country’s mobile internet use by 10% correlates with an average 2 percentage-point increase in gross domestic product, and electronic channels have proved capable of making governments more responsive to civic complaints, too. By contrast, women and people living in rural areas lag behind in online use, which limits their access to government services, banking, and job opportunities.

Nowhere is that clearer than in Africa, which has the world’s lowest share of people using the internet, under 25%. The cohort of 800 million offline people spread across the continent’s 54 countries is younger and growing faster than most, but incomes are lower and a larger share of residents live in rural areas that are tough to wire for internet access—or, for that matter, electricity. Now, however, a handful of phone purveyors are trying in greater earnest to nudge internet-ready upgrades into African markets, with models designed with an eye toward rural priorities (first those of rural India, where they’re already hits), rather than battered thirdhand flip phones from the heyday of the Spice Girls.

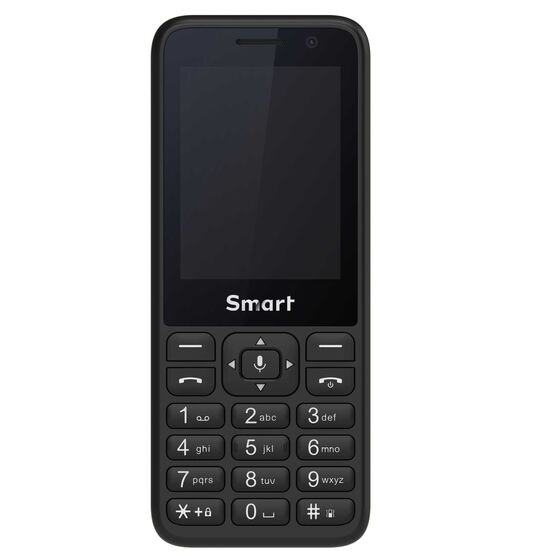

Two of the biggest mobile phone operators in Africa, MTN Group Ltd. of South Africa and France’s Orange SA, this year started selling quasi smartphones for as little as $20. Previously the floor had been around $40, well out of reach for many people. These devices, which have a smartphone brain in the body of 1990s candy bar phones, are powered by software from KaiOS Technologies Ltd., a three-year-old spinoff of a Chinese electronics giant that picked up the pieces from a failed effort to produce cheap internet devices.

Most companies are trying to make internet-connected devices ever more powerful and capable, but KaiOS went the other way. It rethought everything to keep the essential capabilities of smartphones but strip out costs and preserve battery life for people who likely have spotty access to electricity. MTN said in a statement that its KaiOS phones are designed to pull down barriers to the internet’s benefits. Bertrand Gouze, a vice president for Orange’s operation in Africa and the Middle East, says the KaiOS devices offer an alternative to the more expensive phones that remain “out of reach to many Africans and contribute to the digital divide.”

The body of a KaiOS phone is as basic as it gets. There’s no touchscreen, which tends to be the priciest smartphone component and a battery hog. The models that Orange sells—named Sanza, after a handheld musical instrument typically found in central and eastern Africa—have a screen that’s less than half the size of the latest iPhone’s and controlled with an old-school keypad. The keys are made from the least expensive plastic possible. In Nigeria, Rwanda, and other countries where MTN has just started selling KaiOS phones, they’re designed for 3G networks, because 4G coverage doesn’t reach two-thirds of MTN’s 230 million regional customers.

To save money, KaiOS also shrank the memory to about one-quarter or less that of the cheapest Android smartphone. That means the phones can handle only one task at a time—no hopping back and forth from your group text to look up stuff on the web. For some KaiOS models, Qualcomm Inc. refashioned an old version of its processor, the phone’s brain, at an estimated cost of about $3, compared with the roughly $50 version found in top-end smartphones. In total, KaiOS-powered phones are made from about $15 worth of parts, estimates Wayne Lam, an analyst with researcher IHS Markit Ltd. Materials for the next-cheapest comparable phones cost at least twice as much, and Apple Inc.’s top-of-the-line iPhone has $390 worth of stuff.

That doesn’t mean these scaled-down phones aren’t capable. All the cut corners result in a device that uses so little power, Orange says, it can last as long as five days on a single charge. The lack of a touchscreen also makes voice commands more valuable, so there’s a giant button in the middle of the phone that activates a version of Google Assistant adapted for local markets. Google invested $22 million in KaiOS last year and contributed to a fresh $50 million funding round announced on May 22.

In ways both high-tech and low-tech, internet providers are putting in the effort to make getting online feasible in conditions that tend to beat up on silicon. Nairobi’s BRCK Inc. builds computers with cheap off-the-shelf parts to beam out connectivity from solar-powered rural cell towers and to serve as Wi-Fi hotspots on informal commuter buses called matatus. To make sure the machines can survive both hot expanses and the possibility of being hosed down by matatu drivers, BRCK houses the computers in aluminum cases that can guard against the elements.

One problem the carriers haven’t solved is the high price of mobile data. Every gigabyte costs the average African a relatively massive slice of monthly income—about 9%, compared with less than 0.5% in the U.S., according to the Alliance for Affordable Internet, a coalition of companies, governments, and advocacy groups. Facebook Inc. has developed special software for mobile carriers that it’s giving away in a bid to lower costs to consume its content.

Market-research company Strategy Analytics Inc. expects sales of phones powered by KaiOS to jump 50% this year, to 105 million devices, making it the fastest-growing major phone OS in the world. Most of that growth will likely come from India, where the billionaire head of conglomerate Reliance Industries Ltd. spent tens of billions of dollars to build a nationwide mobile internet network from scratch and extensively subsidize the phones.

Like India and the rest of the world, Africa can’t afford to ignore the poisonous downsides of the internet, notably its capacity for spreading hate speech and misinformation. Yet like energy and transportation, internet access has become an essential component of infrastructure, economic development, and social empowerment, so much so that authoritarian governments in parts of the continent have tried to block access to it entirely. The growing sweep of KaiOS offers a reminder that the most important innovations aren’t always the driverless cars, the pilotless planes, or the sailorless boats. Sometimes they’re a $20 phone.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Max Chafkin at mchafkin@bloomberg.net, Jeff Muskus

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.