The Kremlin Dismisses Climate Change as the World Heats Up

The Kremlin Dismisses Climate Change as the World Heats Up

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- When coordinated climate demonstrations swept the globe on Sept. 20, 300,000 people rallied at City Hall in New York, 270,000 gathered outside Berlin’s Reichstag, and 90,000 thronged downtown Sydney. In Moscow, a few dozen students assembled with cardboard placards around a statue of Pushkin a mile from Red Square. While the movement got blanket coverage in many countries, in Russia it went largely unnoticed in the press and on social media. “People here don’t understand the gravity of the situation,” says Arshak Makichyan, a 25-year-old violinist who helped organize the protest in Moscow.

Public apathy about climate change mirrors indifference in the Kremlin, where the interests of the energy sector are paramount—the oil and gas industries employ more than a half-million people, and almost 50% of government revenue comes from taxes on carbon fuels. Rather than embrace cleaner energy, Russia is introducing bigger tax breaks for oil exploration and boosting coal production. For President Vladimir Putin, the best low-carbon alternative is nuclear power—provided by Russia’s state-controlled Rosatom Corp.—a technology he pitched at an October meeting with African leaders in the Black Sea resort of Sochi.

The slow pace of Russia’s shift away from carbon is increasingly risky as the European Union, the biggest buyer of the country’s oil and gas, prepares a plan to reduce net emissions to zero by 2050. A key proposal is a carbon tax on energy imports into the EU, which the Center for Environmental Investments, a Russian research house, says could cut Russia’s energy exports by a third in the coming decade.

With prices for renewable energy in some places below those for power from burning carbon, some forecasters predict oil demand will start falling within five years, about a decade earlier than Russia planned for. That could render obsolete a dozen multibillion-dollar oil and gas projects in Siberia and the Arctic. “Russia risks being caught out by the speed of change,” says Kingsmill Bond, a strategist at Carbon Tracker, a London researcher that estimates major energy companies must reduce production by a third by 2040 to keep global warming below 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit), a goal of the Paris Agreement on limiting greenhouse gas emissions. “They’re anticipating that everything is going to be fine for the foreseeable future.”

Russian scientists say parts of the country’s Arctic are heating up faster than anywhere else in the world, and vast swaths of Siberia were ravaged by flooding and forest fires this summer. But while Putin in September finally decided to ratify the Paris Agreement after years of foot-dragging, he says he doesn’t believe global warming is caused by human activity, and Russia isn’t making any proposals to cut its carbon output. On Nov. 13 in Brazil, Putin conceded that Russia must do more to promote renewables, but at a conference in Moscow a week later he said a wholesale shift to wind and solar power risked “humanity once again ending up in caves” and that countries embracing zero carbon policies to combat climate change are “pursuing their own agenda.” That message, amplified by Kremlin-controlled media, has shaped citizens’ attitudes. Russia’s Public Opinion Foundation says almost 40% of Russians believe nothing can be done to prevent climate change, and 10% don’t think global warming is happening at all.

The oil industry and government officials dismiss warnings about the risks Russia faces as an attack on big business. In November the Economy Ministry nixed a proposal by Anatoly Chubais, the architect of Russia’s privatizations in the 1990s and a backer of renewable energy projects, to tax corporate carbon emissions. Instead, Russian officials have suggested the country needs to produce as much oil as it can while demand holds up. “We may think that we have outsmarted everyone and can easily get away with avoiding this tax right now, but five to 10 years down the line we will discover that we’ve shut down our own exports,” Chubais told state-run news agency RIA Novosti in June. “That’s a very painful situation.”

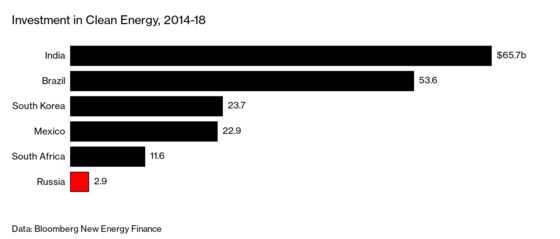

Russia isn’t alone in banking on a slow transition to clean energy. The U.S. president and most big oil companies are doing the same. The risk for Russia is that it’s planning for a gradual transition without hedging its bet. Greener sources, not including Soviet-era hydropower dams, account for less than 1% of Russia’s total energy output, and state oil company Rosneft offers no concrete plans on renewables in its 2022 outlook. The latest national energy strategy acknowledges a need to expand renewables, but the government continues to offer lavish subsidies to oil companies and scant support to green power providers. That, says Niclas Frederic Poitiers, a research fellow at Bruegel, a Brussels think tank, leaves Russia at risk if other industrialized countries—particularly those that buy the bulk of its oil—seek to reduce their dependence on carbon fuels. “Russia has to start thinking about that now,” he says, “while they still have revenues from the natural resource sector.”

Read more: Here’s How Climate Change Is Viewed Around the World

To contact the editor responsible for this story: David Rocks at drocks1@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.