The End of the Jaffa Orange Highlights Israel Economic Shift

The End of the Jaffa Orange Highlights Israel Economic Shift

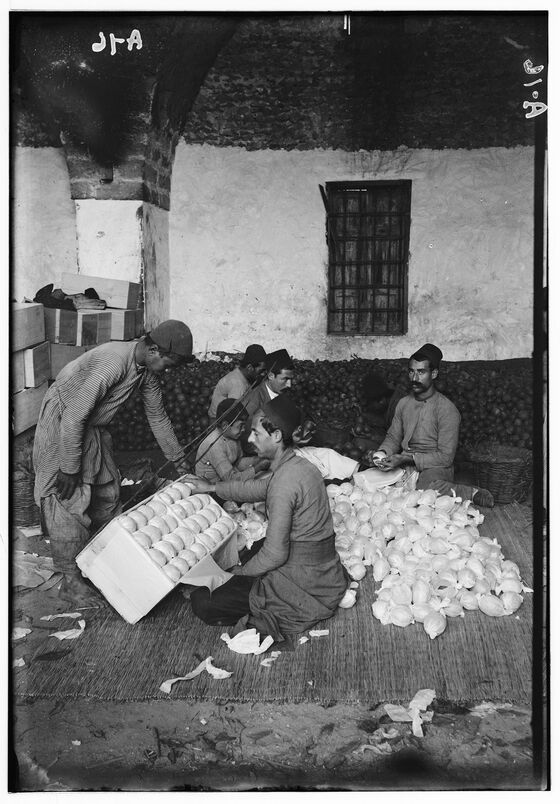

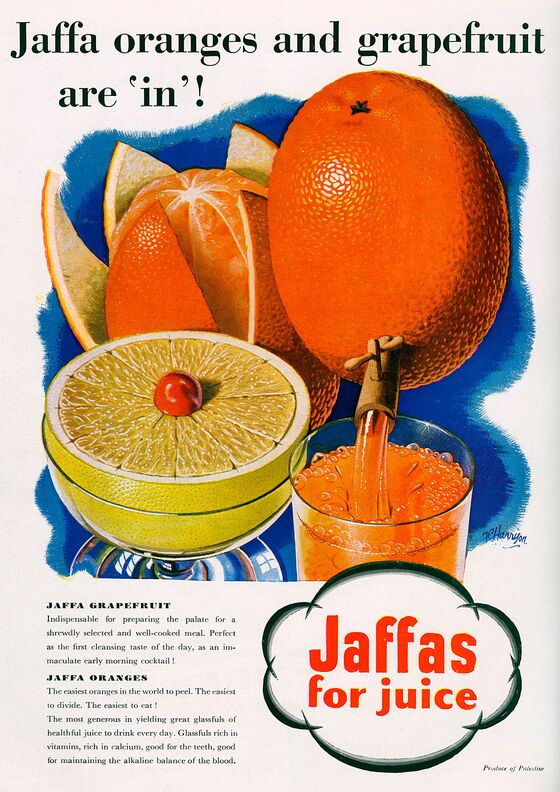

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Almost two centuries ago, Ottoman farmers in what’s now Israel began cultivating a new citrus variety, a sweet-but-tart-and-juicy delicacy called the Jaffa orange—named after the historic port city adjacent to today’s Tel Aviv. Exports surged as gourmands across the Middle East and Europe fell in love with the fruit, and the Rothschild family made citrus plantations the economic foundation of their efforts to create a home for Jews in the region. When refugees flocked to the area in the early 20th century, they quickly saw the potential of the Jaffa orange to fund the state they dreamed of building.

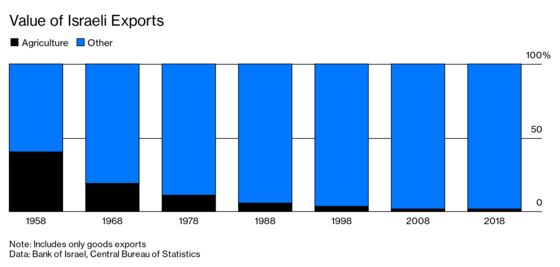

But in recent years, the fruit has fallen on hard times. Since peaking in the early 1980s at 1.8 million tons a year, Israeli citrus production has dropped almost 75%. That decline highlights Israel’s shift away from its socialist, agrarian roots and its emergence as a tech powerhouse. With a strengthening currency making exports less competitive and scarce water supplies raising the cost of cultivation, oranges—and many other crops—are no longer worth the effort. Agriculture has fallen to 2% of goods exports, from a peak above 40% in the 1950s, as the plains and gentle hills around Tel Aviv have been bulldozed to make way for malls, apartment blocks, and office parks for growing ranks of software coders and pharmaceutical researchers. “Land here in the center of Israel is so expensive, most of the orchards were cut down,” third-generation orange grower Idan Zehavi says in the grove first planted by his grandfather.

Just 1% of Israelis now work in agriculture, down from 18% in 1958, while the tech sector has shot up from virtually zero to 10% of jobs today, many developing software used outside the country. That’s helped double exports of services since 2008, to more than $50 billion last year—with services in 2020 poised to surpass goods exports for the first time. The shift “from basic agriculture like Jaffa oranges to top-of-the-line tech” makes economic sense, says Karnit Flug, former governor of the country’s central bank, now a vice president at the Israel Democracy Institute research center. “Israel doesn’t have any comparative advantage in agriculture. Water is not abundant here. Land is not abundant here.”

The changing fortunes of farmers were a potent political issue in the election campaign that ended on March 2, Israel’s third in the past 11 months. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu—who won a plurality in voting—promised stronger support for agriculture to lower food prices. “You’re real patriots,” Netanyahu told farmers in December. “You protect the land, and we will protect you.” His primary rival, Benny Gantz, who grew up in a farming community, pledged to allow entry to more foreigners to work the fields to double farm exports within five years. Farmers “guard the borders, open territories, and offer food security,” Gantz wrote on Facebook.

One sector that’s prospering even as farming suffers sits at the intersection of tech and agriculture. The country has more than 200 startups in that field, with venture capitalists more than doubling annual investment over the past five years, to $100 million-plus in 2019, according to Start-Up Nation Central, a business advocacy group. Netafim, a pioneer in drip irrigation started in 1965, has added sensors and software that allow farmers to precisely control the water their crops get. Taranis, founded in 2015, provides high-resolution aerial imagery to help growers decide precisely where they need to apply more water, pesticides, or herbicides. And Vertical Field, founded in 2006, is expanding to the U.S. with its technology for growing plants on walls, allowing for more efficient use of space—and water. “We’re using every drop,” says Chief Executive Officer Guy Elitzur.

Orange farmer Zehavi says he spends about 2,000 shekels ($580) a month on water for his 600 trees in the summer months—whereas rivals across the border in Egypt pay nothing for water. While Israeli farms are among the world’s most efficient in irrigation, the cost of water, combined with rising salaries and the shekel’s 21% appreciation against the dollar this century, has priced the country out of many export markets. Agriculture workers in Israel earn about $2,200 per month, 10 times what similar jobs in neighboring countries pay. In regional rivals such as Egypt, Turkey, and Morocco, “labor is very cheap, and water is very cheap, and the currency is better for exporters,” says Nitzan Rottman, who oversees work on citrus at Israel’s Ministry of Agriculture. “We can’t compete with them.”

Some farmers are shifting from crops such as oranges—water-intensive even with the best irrigation systems—to less-thirsty alternatives such as grapes, olives, and Argania spinosa, the nut tree that produces argan oil for shampoos and skin creams. And climate change, which has made rainfall more volatile and increased fears of a prolonged drought, has accelerated that shift, says Elaine Solowey, who teaches sustainable agriculture at the Arava Institute, a research center in Israel’s bone-dry Negev Desert. “We don’t want to be caught in a trap as far as water goes,” she says. “We’re hoping to start diversifying and have other orchards ready relatively quickly.”

With suburban development encroaching on his five acres of Jaffa orange trees, Zehavi came up with a different solution: a pick-your-own operation. When he pilots his tractor along the road linking the two sections of his orchard about a half-hour south of Tel Aviv by car, he says, “People look at you like, Where the hell did you come from?” But those suburbanites, nostalgic for a slice of the Israel of their grandparents, flock to his grove on weekends to pick bushels of oranges for 7 shekels a kilo. “I want children to see where oranges come from,” he says. “And it’s not just from the supermarket.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: David Rocks at drocks1@bloomberg.net

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.