The End of the Cult of Ghosn

The End of the Cult of Ghosn

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Carlos Ghosn has long been a larger-than-life figure in the auto industry, a globe-trotting force who developed and defended the Renault-Nissan alliance in the face of squabbling shareholders and competing government interests. On Nov. 19 the myth of Ghosn unraveled. He was arrested in Tokyo on allegations of hiding the true amount of his pay from securities regulators in what Nissan Motor Co., where he was chief executive officer from 2001 to 2017 and later chairman, called years of serious misconduct. The news threatened an abrupt end to one of the auto world’s most illustrious careers and throws the future of the Franco-Japanese auto alliance into doubt.

At a late-night press conference after the charges were revealed, Nissan CEO Hiroto Saikawa—a former Ghosn confidant—painted a dark picture of an executive with too much power and too little oversight, which he said spurred the alleged misconduct. “It was regrettable, but I more strongly felt indignation and personal despair,” Saikawa said, sitting alone behind a desk at Nissan’s Yokohama headquarters. The CEO also took a swipe at the Renault-Nissan partnership, saying the Japanese market had been undervalued and some product decisions biased.

In France, where the state owns 15 percent of Renault SA, officials were quick to demand continuity in a pact that gives more power to the French side. President Emmanuel Macron said he’d remain “extremely vigilant” regarding the stability of the alliance. On Nov. 20, Renault named Thierry Bolloré deputy CEO and put him in charge of the company temporarily, but didn’t dismiss Ghosn. Bolloré, whom Ghosn had appointed as chief operating officer in February, had already been effectively anointed as the next CEO.

Ghosn hasn’t been seen since his Gulfstream corporate jet (registered as N155AN) touched down at Tokyo’s Haneda Airport on the evening of Nov. 19. Asahi News broadcast footage of men in suits boarding the plane and lowering the blinds, but Ghosn wasn’t visible. He didn’t answer emails, phone calls, or text messages, and several close associates say they’ve had no contact with him. Prosecutors say Ghosn failed to declare some 5 billion yen ($45 million) in income on Nissan’s official securities reports from 2011 to 2016. They haven’t revealed any other details, and there’s no clear timeline for the case, but a suspect in Japan can be held for 23 days without charges.

Local press reports say Ghosn’s financial filings didn’t fully reflect what the company paid for residences in Amsterdam, Beirut, Paris, and Rio de Janeiro that had no legitimate business purpose. Other reports followed up on misdeeds Saikawa hinted at during his news conference, saying Ghosn may have charged vacation expenses to the company, pocketed compensation approved by shareholders but intended for other executives, and used funds earmarked for investment to buy real estate for himself via overseas units. “To not have understood that he could be caught exhibits a belief that he’s invincible,” says industry analyst Maryann Keller. “He was a superhero. His status gave him the power to really control Nissan.”

The turmoil resulting from Ghosn’s downfall speaks to his outsize role in holding together a house he almost single-handedly built. The Renault-Nissan alliance was a chimera: a creation of often-uncomfortable cross-shareholdings between France and Japan melded by an indispensable leader—Ghosn. As CEO of Renault and chairman of Nissan and its new partner, Mitsubishi Motors Corp., the 64-year-old was the common denominator and driving force of the partnership, first formed in 1999, when Nissan was near collapse. More than once since then, Ghosn stepped in to appease bickering shareholders, and his departure leaves no obvious person to fill that role. “This alliance is quite heavily bound up in the personality that is Ghosn,” says Demian Flowers, an analyst at Commerzbank AG in London. The prospect of greater integration or a merger “just took a big step back.”

For now, at least, many investors seem to agree. Questions about life without Ghosn weighed on shares of Renault, which ended down 8.4 percent on the day of his arrest, hitting their lowest level since January 2015. In Japan, Nissan’s stock slid more than 5 percent on Nov. 20. “It is hard not to conclude that there may be a gulf opening up between Renault and Nissan,” says Max Warburton, an analyst with Sanford C. Bernstein & Co.

At his press conference, Saikawa sought to quell any speculation of an outright rupture among the businesses, saying Ghosn’s departure wouldn’t affect the tieup, which he called bigger than just one person. Kenneth Courtis, chairman of private equity group Starfort Investment Holdings LLC and a former vice chairman of Goldman Sachs Asia, says that given the huge investments the industry faces in the transition to electric cars and autonomous driving, “it’s probably suicidal to break up the alliance.”

Ghosn built his reputation as a turnaround specialist by bringing Nissan back from the brink—the stuff of legend in Japan, where Nissan’s deep slide in the 1990s had been something of a national tragedy. Its revival made Ghosn a hero there, with a manga, or comic series, detailing his exploits as a corporate genius. When the alliance fell into crisis after France boosted the state’s stake temporarily to win a shareholder vote in 2015, Ghosn defused the situation by playing the role of chief automotive diplomat.

Still, he never managed to fully bridge the cultural differences. Even the probe into his alleged misconduct reveals the fault lines: It was sparked by a whistleblower investigation at Nissan that Renault didn’t hear about until late in the process. “The Japanese do not want the greedy plutocracy, the greedy CEO culture,” says Jesper Koll, CEO of asset manager WisdomTree Japan. The Ghosn case “sends a strong signal that yes, you are a leader of a public company, but no, you cannot enrich yourself and just become this superstar.”

For the Japanese, the lopsided power structure is particularly grating because of Nissan’s success: The company now sells more cars than Renault, and its market value is almost double that of its French partner, but Nissan has little say in the alliance. Renault owns 43 percent of Nissan, giving it a strong voice in strategic decisions there. The Japanese company’s 15 percent stake in Renault, by contrast, doesn’t carry any voting rights. Saikawa has been unenthusiastic about the relationship. Following a Bloomberg News report that Renault and Nissan were in talks to merge under a single stock, he told the Nikkei news service in April that he saw “no merit” in combining the companies. He said such a move would have side effects, though he later stressed the importance of the alliance.

The discord may have gone deeper, however. The Financial Times reported on Nov. 20 that Ghosn had been planning a full merger of Renault and Nissan before his arrest, citing unidentified people familiar with the matter. Nissan’s board was opposed to such a deal and looking for ways to block it, according to the newspaper.

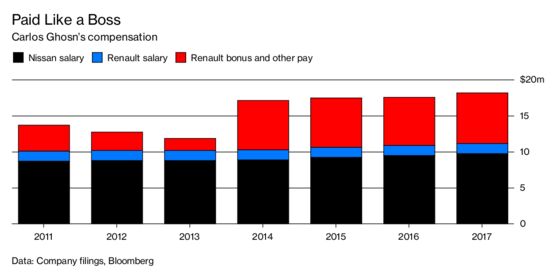

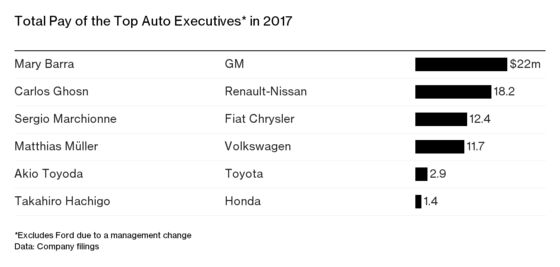

Nissan said it had been investigating Ghosn and Nissan Director Greg Kelly—who was also taken into custody—for several months, and the board was set to meet on Nov. 22 to decide on removing them. Both men reported pay to securities regulators in Tokyo that was less than the actual amount, Nissan said. Ghosn’s compensation in the most recent fiscal year was $6.5 million at Nissan, $8.5 million at Renault, and $2 million at Mitsubishi. Japanese media also reported that prosecutors had agreed to a plea deal with an unidentified person at Nissan.

A Brazilian-born French national who received his early education in Lebanon, Ghosn spent 18 years at tiremaker Michelin, rising up the ranks to run its North American division. From there he moved to Renault, where he was executive vice president from 1996 to 1999. He was then assigned to turn around Nissan, where he reduced the company’s purchasing costs, shut factories, eliminated 21,000 jobs, and reinvested the savings in 22 new car and truck models in three years. As the alliance grew—Renault-Nissan-Mitsubishi today rivals Toyota Motor Corp. or Volkswagen AG in size—so did Ghosn’s reputation. He was a regular on panels at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, and other international conferences, discussing the future of transportation and industries facing disruption.

The upheaval comes at a pivotal time for the industry, which is preparing for the shift to self-driving electric cars and facing upstarts such as Uber Technologies Inc. and Alphabet Inc.’s Waymo. Ghosn was among the first traditional auto bosses to embrace electric vehicles, spearheading the rollout of the Nissan Leaf in 2010, when battery-powered cars were still an oddity. He’s predicted small companies will have a hard time keeping up, making scale vital for survival. Salvation for the car industry requires more than just building automobiles, Ghosn insists. “You’re going to see clusters of carmakers, of tech companies, software companies, align in order to bring this offer to the market,” he said in an October interview with Bloomberg TV.

While Ghosn moved to pass the baton—appointing Saikawa to run Nissan in 2017 and flagging Bolloré as a “good candidate” to lead the French carmaker—the alliance has a limited management structure. “Ghosn always put himself in the position of appearing indispensable,” says Jean-Louis Sempe, an analyst at Invest Securities SA. His departure would “bring forward the issue of the longevity and the evolution of the alliance.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Ellis at jellis27@bloomberg.net, David Rocks

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.