The Covid-19 College Gap Year Exposes a Great Economic Divide

The Covid-19 College Gap Year Exposes a Great Economic Divide

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Sunny Hostin, a host of ABC’s The View, shared some wonderful news several weeks ago on her program: Her son got into Harvard. But Gabriel Hostin won’t be going this fall. He deferred his admission so he can avoid burnout. He’ll also sidestep the worst of the pandemic. “I see a gap year as all about self-exploration, self-enrichment, community service, and maturity, learning where you are in the world,” Gabriel says. “I’m blessed to be in the position I am in.”

Jason Li, whose parents grew up in rural China, won’t be waiting to start his college education. Li, who turned down Harvard in favor of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, is all in, even if he has to study online. “I don’t expect it will be a completely normal semester, but I’m going no matter what,” he says. “MIT has been my dream school forever. They’re giving me really good financial aid.”

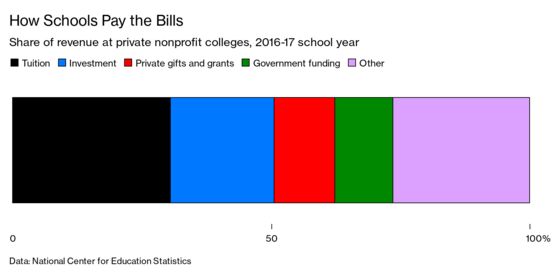

The diverging paths of the two 17-year-olds demonstrate one of the many perils facing higher education this fall: the socioeconomics of college deferrals. Students taking gap years tend to be more affluent, better able to afford a $75,000-a-year private college—and the expense of taking an extended break before enrolling. But if too many of them put off their studies, it could smash the economic model underpinning the U.S.’s $600 billion-plus higher education industry. Private colleges rely on tuition and fees for 30% of their revenue.

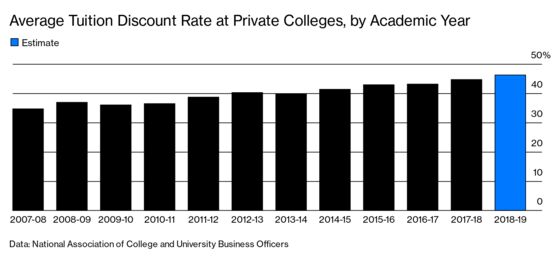

For decades, schools have billed higher prices to affluent families while charging less, or nothing at all, to high-achieving students of modest means. On average, for every $1 that a private college charges, almost 50¢ goes for financial aid, according to the National Association of College and University Business Officers.

“It’s kind of a run on the bank if a significant enough share of the students who can pay decide they’re not going to go,” says Matt Maguire, a vice president with Maguire Associates, which has consulted with schools such as Harvard, Amherst, and Rice. “Then the bottom falls out, and how are they going to deal with that?”

In a recent survey of 6,700 parents and students, most of them high school seniors, Maguire found that 12% are considering deferring enrollment this fall, many times the typical proportion. Even worse, 30% of international students, who generally pay a college’s full cost, are considering a postponement. If many kids on scholarship take their place, colleges could find themselves in a deep hole.

A surge in gap years could start a “chain reaction” that may leave institutions unable to make their budgets, according to Craig Goebel, a principal of Baltimore-based education consultant Art & Science Group, whose own survey also found a jump in students expecting to ask to defer for a year.

It’s no secret why many want to wait. This fall is expected to look very different from years past. While colleges don’t know today what will happen once classes resume, they’re discussing options such as a staggered return, a combination of online and in-person classes, social distancing, and the cancellation of activities including sports and theater.

Christine Pluta, a private college counselor at Edvice Princeton, says many full-paying students are asking about putting off their studies. They want to wait for the “normal college experience,” says Pluta, a former admissions officer at the University of Pennsylvania and Barnard College.

Not so at programs that help high-achieving, lower-income students get into selective colleges. Consider Prep for Prep, a 40-year-old nonprofit that recruits and helps prepare New York City children of color to go to private schools and then to top colleges. Only 1 of 132 high school graduates in its program this year asked for a gap year, according to Shari Fallis, director of college guidance.

Similarly, at College Match, a nonprofit that works with 30 Los Angeles schools, only 1 of about 200 is even considering asking for a deferral. The majority are like Li, the high schooler headed to MIT, who worked with the program. Josue Estin, the 18-year-old son of a housekeeper and a plumber, is going to Amherst College on a full scholarship. “Part of it comes down to, I persevered so much,” he says.

Counselors are encouraging College Match students to go ahead and enroll this fall because they shouldn’t risk forfeiting a life-changing opportunity. Lower-income students often benefit from the high graduation rates, small classes, and vast resources of selective schools. Still, the organizations worry about the prospect of starting out online, where less affluent students tend to struggle. Some may have trouble finding internet connections and quiet places to study. “We foresee that being a huge challenge for our students,” says Erica Rosales, College Match’s executive director.

Until this year, schools had often encouraged gap years—with some giving aid so low-income students participate—because many studies have shown deferrals can give burned-out students a chance to recharge and even improve future academic performance. Gap years can range from a break to work in a coffee shop to a formal experiential or educational program whose costs can rival a college’s tuition.

Hostin, the View host, says her son had been considering taking a year off before college last fall, and some friends were skeptical about the wisdom of the break. Now they’re thinking about following suit. “They don’t want to pay for an online experience at the cost of an Ivy League tuition,” she says.

Such thinking has left some institutions concerned about having enough students to fill up their classes and make their budgets. Schools including Brown and Cornell say they won’t automatically grant deferrals. Colleges usually ask for a good reason and a plan; concern about a diminished experience during the pandemic isn’t enough. Amherst says it may limit gap years because it doesn’t want to fill up so many future spaces that a year from now there won’t be enough room to accommodate current high school juniors. At Princeton, accepted students who ask to defer may have to wait more than a year before they can begin because of enrollment and housing constraints. And at some other schools, admitted freshmen will either have to attend or forfeit their acceptance and gamble on reapplying after the crisis.

“I don’t blame students and parents for feeling concerned about what the experience will be like to be doing online classes in the fall and not having all the other elements,” says Holly Bull, president of the Center for Interim Programs, which counsels families researching gap years. “If my daughter was a senior this year, I would have serious concerns about her stepping into that—and paying the tuition.”

Even those who can wait a year face challenges. Amid the pandemic, they won’t be able to sling a backpack over their shoulders and head to Europe. And that internship at the community theater or nonprofit? They’re heading into a job market that looks like the Great Depression.

In Newton, Mass., the Goodmans had encouraged their high school senior, Sophie, to take a gap year before starting Harvard. The school has greenlighted the plan. Well before the pandemic hit, she’d wanted a break from academics. Her parents, both Harvard alums, had taken time off themselves.

Part of their daughter’s pre-virus gap year plan: teaching circus arts in Costa Rica. “That is clearly not going to happen,” says her father, Mark, who runs a boutique fitness company. So Sophie is looking at alternatives such as working on an organic farm or a political campaign. If those ideas don’t pan out, then what? A gap year in her parents’ house? “That,” her father says, “is the challenge she faces.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.