How One Crash 10 Years Ago Helped Keep 90 Million Flights Safe

How One Crash 10 Years Ago Helped Keep 90 Million Flights Safe

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Investigators never figured out precisely why the pilot abruptly sent the Colgan Air turboprop into a fatal dive 10 years ago as it neared Buffalo, N.Y.

But they did learn enough from the Feb. 12, 2009, crash, which killed 50 people, to make it one of the most important milestones in the history of aviation safety, leading to changes in everything from pilot training to managing fatigue.

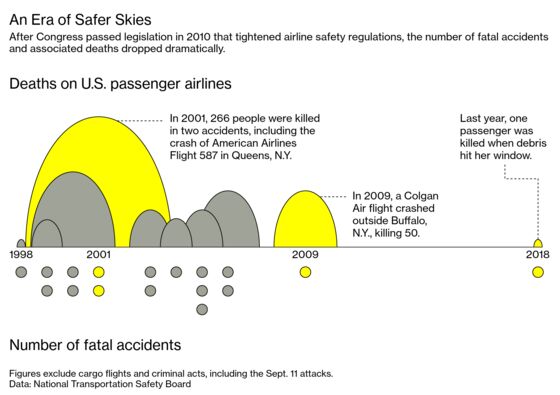

The reforms have contributed to an unprecedented decade of safety: There hasn’t been another accident with multiple fatalities on a U.S. passenger carrier anywhere since the Colgan disaster. In fact—outside of crashes of foreign carriers or cargo planes—there has been only one passenger death.

“Colgan Air was truly a watershed event,” said Robert Sumwalt, the chairman of the National Transportation Safety Board who served as a board member when the accident occurred. “The safety record bears out the impact that this crash, that this tragedy, had in ultimately improving safety.”

Coaxed and prodded by an unusually well-organized group of family members representing the victims, Congress passed a law in 2010 enshrining several of the safety board’s recommendations from the accident into law.

The action broke a decades-old logjam that had stalled new regulations on pilot fatigue as airlines and unions sparred over proposed rules. Under orders from Congress, the government completely revamped how airlines schedule pilots. It also helped prompt dramatic improvements in how pilots are trained to handle flights that go out of control, which is by far the biggest killer in commercial aviation.

Other actions increased the use of flight data to probe for hidden risks, improved vetting of pilots before they were hired, and required major airlines to disclose to passengers when they were flying on a separate regional carrier.

Continental Connection Flight 3407 from Newark, N.J., to Buffalo—a turboprop operated by the now-defunct regional carrier Colgan Air—had taken off late. As it approached its destination shortly after 10 p.m., other pilots were reporting icing conditions as light snow fell.

About six miles from the airport, the plane shot up, quickly lost speed as it climbed, and then plummeted into a neighborhood in Clarence Center. All 49 people aboard and a man on the ground died as fire engulfed a house.

At first, attention focused on the potential that ice had disrupted lift on the wings. But flight data soon revealed the real reason for the abrupt maneuvers: Captain Marvin Renslow, reacting to a cockpit warning, had commanded it, according to NTSB records.

The warning occurred because the plane had slowed to below the recommended speed, but it was not yet in danger. Instead of adding power or lowering the nose—techniques every pilot learns from the time they begin flight training to handle such a situation—Renslow did the inexplicable, violently yanking the nose skyward, according to the NTSB.

Investigators spent months without success trying to figure out why he had reacted that way. But they did find clues about the accident and aviation safety in general.

Both Renslow and co-pilot Rebecca Shaw hadn’t slept much the night before. Renslow had apparently slept in the airline’s crew room in Newark, but was up at least part of the night. He had logged in to an airline computer system at 3:10 a.m. Shaw had taken red-eye flights from the West Coast the night before and was recorded in the cockpit saying she didn’t feel well as they prepared to depart.

Renslow’s flying skills also came into question. Records revealed that he had repeated difficulty passing the flight tests pilots undergo as they qualify for new planes or periodically demonstrate proficiency. In all, he had outright failures on six occasions, an unusually high number, according to the NTSB.

Family members of the victims began learning these details in May 2009 as the NTSB held a hearing on the crash. They were stunned, said Scott Maurer. His daughter Lorin, 30, was on board the flight.

“It was just an avalanche of bad news that clearly pointed out that this thing could have been prevented,” Maurer said in an interview as the group, known as Families of Continental Flight 3407, prepared for a series of memorial events being held this week in Buffalo.

There was no one thing that stood out. Instead, a litany of issues emerged, including how pilots commuted to the job, a failure to follow rules barring nonwork conversations in the cockpit, and inadequate training for emergencies, he said. Family members fanned out to the halls of Congress and federal agencies, relentlessly pushing for change.

Margaret Gilligan had just taken over the Federal Aviation Administration’s safety oversight branch a few weeks before the crash. The public’s view of aviation accidents was changing, spurring more outrage, and the Colgan crash hastened the shift, Gilligan said.

“It came at a pivotal time” in which the public became “much less accepting of risk in aviation than it had been,” she said. “It took on a very different perspective than other accidents had up until that time.”

The actions that followed on pilot rest rules are a good example, she said. Even though the NTSB ultimately decided there wasn’t enough evidence to say pilot fatigue had contributed to the accident, the investigation exposed widespread practices allowing flight crews to operate with limited sleep. Congress ordered the FAA to rewrite its regulations on pilot scheduling.

“It gave us the chance on all sides to really come together to do something we knew needed to be done,” Gilligan said.

There have been deaths since the Colgan Air crash, but there haven’t been any accidents involving multiple fatalities on a U.S. passenger carrier.

Two United Parcel Service Inc. pilots died on Aug. 14, 2013, when their plane struck a hill short of the runway in Birmingham, Ala. There was also a fatal accident in 2013 on U.S. soil involving Asiana Airlines that killed three. Asiana, as a foreign carrier, wasn’t subject to many of the post-Colgan reforms.

Other recent events haven’t injured anyone but could easily have become catastrophic. An Air Canada plane passed within feet of several planes on the ground in San Francisco on July 7, 2017, after pilots mistakenly tried to land on a taxiway instead of the runway.

By contrast, there were 474 deaths on passenger carriers in the decade prior to the Colgan crash. That doesn’t include the 265 people killed on planes in the terrorist attacks of 9/11, which are classified as criminal acts rather than accidents.

Elsewhere in the world the accident rate also has improved steadily but it still lags in nations that don’t adhere to standards as rigorous as the U.S., according to data from the Aviation Safety Network. It uses a broader definition of commercial aviation that includes charter operators and cargo carriers.

There were 556 deaths in 15 fatal accidents last year in all nations, which is well below what was typical 10 years ago, according to the group.That includes 189 people lost in the Oct. 29 crash of a Lion Air jet off the coast of Indonesia.

Sumwalt and Maurer said more needs to be done to finish the changes ordered by Congress in the wake of the Colgan disaster. The FAA still hasn’t finished a database mandated by the law that would contain records of pilot performance so airlines can easily check on job candidates, for example.

The database has been delayed by software problems, the agency said in a statement. “In the 10 years since the accident—and with the help of the Colgan families—we have made significant progress across the industry in reducing pilot fatigue, improving pilot training, and raising crew qualifications to reduce or eliminate the types of errors that caused the accident,” the agency said.

By any measure, the safety record since the crash is unprecedented. Out of more than 90 million flight departures on U.S. airlines carrying billions of passengers since then, there has been just the single death: A woman died on April 17 on a Southwest Airlines Co. flight near Philadelphia when an engine failed, sending debris into a window next to where she was sitting.

“Here we are 10 years after this crash, and thankfully there hasn’t been another crash,” Maurer said. “In some way, our family group does feel like we’ve helped make that happen. But credit has to go to everybody. Airlines have stepped up. The FAA has stepped up. All the stakeholders who participated can share in the credit.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jon Morgan at jmorgan97@bloomberg.net, Elizabeth Wasserman

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.