What Chipmakers Tell Us About the Great Global Unwinding

What Chipmakers Tell Us About the Great Global Unwinding

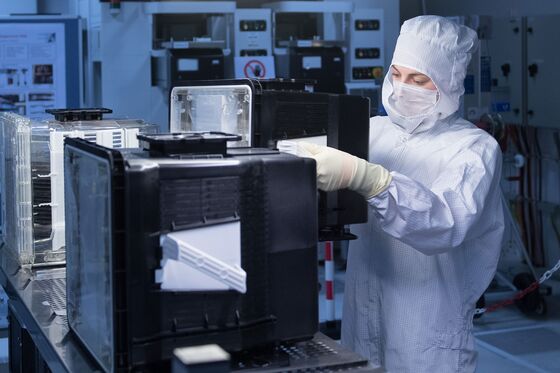

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- When Globalfoundries Inc., the California chipmaker, filed patent lawsuits against rival Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. this August, it was tapping into growing fears that the war for the future of silicon will be fought along stark geopolitical lines. The concern is that TSMC’s dominance has placed control of critical components for the world’s electronics in the hands of one company, in one region, outside the U.S. TSMC has 74% of the market for making chips designed by other companies, according to Bloomberg Intelligence data; Globalfoundries has said TSMC’s share of the most advanced products is more like 90%.

“There’s a lot of concern for chip production being so concentrated, and it’s only becoming more important for everything from aerospace and defense to smartphones and the internet of things,” says Sam Azar, senior vice president for corporate development and legal affairs at Globalfoundries, which has called for the U.S. to ban a range of TSMC imports. “A lot of that production comes from one area in Greater China. A lightbulb should go off saying, ‘Wow, that may not be good for the world.’ ” A spokeswoman for TSMC, which has countersued, says that Globalfoundries’ complaints are “baseless and have no merits” and that it’s fallen behind because of “poor execution” and “its inability to serve its customers with the right technology.”

Globalfoundries’ battle with TSMC, while mostly an intellectual-property dispute, is also symbolic of what industry analysts have described as the potential unwinding of the world’s supply chain. As fallout from the U.S.-China trade war continues, the upheaval is especially pronounced in the chips business. Tariffs and corporate blacklists are remapping the industry, with everyone from Apple Inc. to Huawei Technologies Co. racing to rethink which suppliers—and countries—they rely on for their components. At this point, whether the trade war advances or halts, “global electronics technology is going to bifurcate,” says Gus Richard, a semiconductor analyst at research firm Northland Capital Markets.

Before the arrival of the Trump administration, the supply chain industry had been growing steadily more interconnected. While Apple has long stamped on the back of its products that they’re designed in California and assembled in China, the reality is far more complicated. Their innards are stuffed with teeny circuits that manage things such as memory and processing speeds, energy efficiency, and networking, sourced from myriad global partners to maximize economies of scale. The majority of Apple’s suppliers are based in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and mainland China. But recent fears of 10% to 25% import taxes may upend this ecosystem. Just days before Globalfoundries filed its lawsuit, President Trump tweeted, “American companies are hereby ordered to immediately start looking for an alternative to China” for production.

About a third of China’s electronics manufacturing capacity will move out of the country to Vietnam, India, and elsewhere in Asia, estimates Anand Srinivasan, an analyst at Bloomberg Intelligence. It could take years to re-create the semiconductor industry’s existing operations in these new homes, and component costs will probably go up. To limit the damage, some tech giants have considered taking on certain areas of production themselves, but “you can’t build everything in-house,” Srinivasan says. “The entire silicon supply is built on ‘co-opetition,’ and no one vendor can do it all.”

A more severe outcome could be a so-called silicon curtain of country-by-country restrictions, which could split up chip suppliers between Eastern and Western companies. This could cut off the transfer of technologies, slow the pace of global innovation, and further raise costs for end users. Apple is aggressively seeking tariff waivers on a slew of parts sourced from China. Without them, Wedbush Securities has estimated, Apple could see U.S. iPhone sales slashed by as many as 8 million units in 2020 (out of a projected 77 million domestic units) as a result of consumer price hikes.

The longer-term consequences are already playing out in the development of fifth-generation wireless networks. With Beijing and Washington looking to cut their reliance on each other for new 5G gear, the Trump administration’s Huawei ban is forcing many companies to sever ties without a clear sense of how to fill the resulting supply gaps. Broadcom, Xilinx, and Micron Technology have suffered the most earnings pain from the Huawei supply cutoff. (They all deliver critical parts for Huawei’s phone networking gear.) In the meantime, Chinese companies are working more assiduously to replace their American partners. The most notable success so far is HiSilicon, a Huawei chipmaking subsidiary that’s provided an alternative to Qualcomm Inc.’s chips for high-end smartphones. “The longer the trade war goes on, the more likely that harsh divide will grow,” says Jim McGregor, a semiconductor analyst at Tirias Research. “I can’t think of a single entity it helps. It hurts everybody.”

Globalfoundries’ Azar says he isn’t sure when the dust will settle on the trade war or his company’s suits against TSMC. Whatever happens, he says, tech companies and chipmakers need to return to supply chains that aren’t just clustered on one continent. “Having a manufacturing base in America, in Europe—that’s a competitive advantage for us,” he says. “Be ready.” —With Ian King

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jeff Muskus at jmuskus@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.