That Time Trump Sold the Plaza Hotel at an $83 Million Loss

That Time Trump Sold the Plaza Hotel at an $83 Million Loss

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Late in the summer of 1994, Abraham Wallach, Trump’s original fixer, was determined to save his boss’s favorite property. The Plaza had declared bankruptcy, and its creditors were anxious to sell the hotel to recoup at least some of their original investment. It was a race to the finish. If Citibank and the other lenders found a buyer for the Plaza, Trump would lose the property. But if Trump could identify a buyer first, he might convince that person to let him continue managing the hotel or, perhaps, give him the go-ahead to complete his project to transform the Plaza’s top floors into penthouse apartments. Wallach was resolute that Trump would triumph.

Wallach’s most promising lead was Sun Hung Kai & Co., one of Hong Kong’s largest property investment companies. It was run by the three Kwok brothers, who were among the richest families in all of Asia. Walter Kwok, the eldest brother, was sufficiently intrigued at the prospect of purchasing the Plaza to come for a visit. With his wife, Wendy, and their children in tow, the family was put up in the lavish presidential suite. Over the course of several days, Wallach and Trump wooed the Kwoks, Wallach accompanying Wendy on shopping sprees, while Trump took Walter on golf outings.

One morning, Wallach arrived to pick up the Kwoks for a day of sightseeing. He nodded to the private security guard who had been hired by the family to stand sentry outside the suite’s entrance, and then knocked on the door. There was no answer, so the security guard also knocked. When there was still no answer, the guard called on his walkie-talkie to another guard stationed inside the rooms. He radioed back to say that the family was stuck inside—the door had jammed. Wallach and the guard tried pushing and pulling the ancient door free from its sticky hinges. It refused to budge. As panic set in, Wallach called down to hotel security. Several men arrived with hatchets, which they used to break down the jammed door, after which the traumatized family rushed out in relief.

Wallach took the shaken guests downstairs for tea. “We’re in the Palm Court, and there’s a violinist playing Viennese waltzes, and I started to talk to them, apologizing profusely,” Wallach told me. “I know what’s coming, so I’m listening to the Strauss waltzes, and I said, ‘I could start to cry right now.’ ” Wallach held back tears as he watched his dream of selling the Plaza to the Kwoks evaporate. After he left the Kwoks, Wallach dejectedly walked the few blocks to Trump Tower to relay the bad news.

“[Trump] was very calm at first. ‘A door jammed? What do you mean a door jammed?’ ” recalled Wallach. Then, “It was as if a tsunami and an earthquake had hit at the same time. There were loud shrieks from the 26th floor. ‘A door jammed? A door jammed?’ ”

Trump ran over to the Plaza, “and he started firing people: ‘You’re fired! You’re fired! You’re fired!’ He even fired people who didn’t work at the hotel, who were guests,” Wallach recounted.

As Wallach and the Plaza’s creditors competed to identify a buyer for the hotel, rumors of deals periodically surfaced. The New York Post, for instance, claimed that the wealthy Sultan of Brunei was purchasing the hotel. Trump, maintaining the appearance that he, not the creditors, was in control of the hotel, insisted the story was false and that the Plaza wasn’t for sale. Then, before Wallach could line up a new Plaza buyer, Citibank beat him to the finish line. The bank found not just one credible candidate with deep pockets, but two.

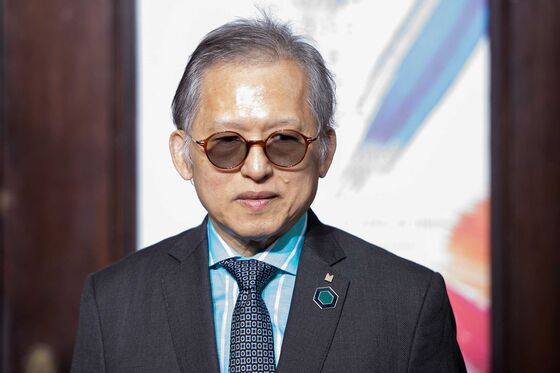

By 1994, it was two years into the Plaza’s bankruptcy and Citibank had begun discussions with Kwek Leng Beng, a billionaire property developer from Singapore. Kwek had recently bought two hotels in Manhattan, the Millennium Hotel located downtown, and the Hotel Macklowe, in Midtown. “One of my principal bankers at Citibank approached me and asked me to look at the Plaza,” Kwek told me. The hotel was well-located and historic, and “had the potential of generating large profits.”

As Kwek was conducting due diligence on the Plaza, Citibank called him again. This time it was to tell him that Prince Alwaleed bin Talal of Saudi Arabia, a fellow billionaire who also happened to be the bank’s largest private shareholder, was also interested in purchasing the property. “I [got] a call to say that Prince Alwaleed would like to form a joint venture with me on the Plaza,” said Kwek. Soon, the two billionaires were partnered. The joint force of Kwek and Alwaleed was a devastating blow for Wallach. One billionaire was bad enough, but two of the world’s richest men, combining their vast resources, would have no need of Trump. Yet, rather than admit defeat, Wallach decided he still had one more move to make.

His first step was to advise Trump to ingratiate himself with Kwek. “I said to Donald, I think it would be beneficial for you to meet him and see if a deal could be crafted where you’re his partner, ” said Wallach. “You manage the hotel, and your position doesn’t really change except you got a partner, but nobody ever listens to who the partner is. All they hear is Trump.” Trump agreed, and soon Wallach and his boss were on the Concorde to London, where the Singaporean’s hotel chain was based.

“When Mr. Kwek arrived at London’s Lanesborough Hotel to meet Mr. Trump, the New Yorker finished signing an autograph for model Elle Macpherson,” the Wall Street Journal recounted, “and then promptly proposed that Mr. Kwek take him as a partner, rather than the prince.” Kwek declined the offer, possibly because Trump’s empire was in tatters and he had already bankrupted the Plaza. Trump, undeterred, then asked whether Kwek would allow him to continue managing the hotel. “Sorry, Mr. Kwek responded: That job was going to the prince’s hotel company.”

When the meeting with Kwek ended in rejection, Wallach turned to other schemes, namely making himself a nuisance. As the talks between Kwek and Alwaleed progressed, executives from both companies converged in New York to discuss the joint venture. “They all come to New York, all the higher-ups on the Saudi side and all the higher-ups on the Kwek side, and where do they decide to stay? In the Plaza hotel, which is still owned and run by Donald Trump,” Wallach told me. It made his job of getting in the way that much easier. “They’re so stupid, they’re staying in his property and they don’t have a clue.”

The executives met in the Plaza’s Vanderbilt suite, sitting in the opulent living room on ornate sofas, discussing specific terms of the proposal. But little did the men know, Wallach was there, too, eavesdropping on the interlopers and scribbling everything they said on a notepad. A longtime doorman had told Wallach that the suite had a secret room, accessed by a back stairway and hidden behind a fake wall. For 10 days, Wallach concealed himself in the cramped space and caused mischief. When, for example, the executives discussed a $100 million loan they planned to take out to buy the hotel, Wallach called the same bank and requested a second $100 million Plaza loan on behalf of Trump, confusing the bankers.

In another instance, which Wallach claims was Trump’s brainchild, the fire department was called. “You hear ‘FIRE!’ And then suddenly, all over 59th Street and Fifth Avenue, firemen come running into the building with hatchets and hoses, and everybody’s required to vacate the building because [it] is deemed structurally unstable,” Wallach told me. A few days of chaos ensued, where the hotel executives were forced to take refuge at another hotel, but eventually the men returned, determined to forge ahead.

Citibank and the other creditors apparently caught wind of the chicanery. “I drove [Citibank] nuts,” Trump later told the Journal. “I did a number on them that you wouldn’t believe.” The bank threatened to hold Trump’s other deals hostage unless Wallach halted his antics and allowed the sale to move forward. So in the end, Trump was forced to call Wallach off. “Donald shows up in my office and says, ‘Abe, we have to stop all of this, we have to stop.’ I said, ‘Why, Donald? We’re really going to be able to create a position for ourselves.’ ” It was then that Wallach became emotional, and Trump, seeing his faithful lieutenant cry, did his best to offer reassurances.

Trump had no choice but to give up the Plaza. He was in the midst of negotiating with Citibank and his other creditors to save what he could of his empire, and he couldn’t risk it all falling apart on the basis of one hotel. So in April 1995, the deal with Kwek and Alwaleed finally closed. It valued the hotel at $325 million, or $83 million less than what Trump had paid seven years earlier. The transaction was complex, with Kwek and Alwaleed agreeing to reduce the outstanding debt on the hotel to about $25 million from more than $300 million, in exchange for each receiving a stake in the hotel of just under 42 percent. Citibank was also to stay in the deal, with a 16 percent equity stake.

Kwek told the Journal that he wanted Citibank to remain an equity partner in the deal to ensure that Trump wouldn’t cause him any further trouble. Trump had a so-called right of first refusal, which allowed him to match any offer for the Plaza—an improbable scenario considering the state of his finances. While Trump was unlikely to execute that right, Citibank, as Trump’s lead lender, had leverage over him. Keeping Citibank involved provided additional insurance that Trump wouldn’t try to interrupt the sale. Several years later, Kwek and Alwaleed would purchase the remainder of the equity from Citibank to become 50-50 owners.

Kwek and Alwaleed also agreed to throw Trump a few scraps: If, under their ownership, the top floors of the Plaza were ever converted into penthouses, Trump would get a cut of the profits. He would also see a small fee if the hotel was sold within seven years. “I was a good listener when negotiating with Trump,” Kwek told me. “He wanted to continue managing the hotel and be part of the venture. We eventually narrowed down his role.”

Trump’s penthouses wouldn’t be built during Kwek and Alwaleed’s tenure as Plaza owners, and the hotel didn’t sell within the allotted time frame, so Trump never saw any profit from the deal. Despite coming out a loser, Trump insisted that he was a part of the new ownership. “We’ll be running the hotel. This is a joint venture. As a joint venture, everybody has input,” Trump told the New York Times. “There will be four partners in the deal,” insisted Wallach, naming Kwek, Alwaleed, Citibank, and “Mr. Trump.”

With Kwek and Alwaleed at the helm, the hotel was under foreign ownership for the first time. “The complexity of the sale announced yesterday, and the international scope of the transaction,” the Times wrote in 1995, “illustrated how the arenas of real estate and finance have grown beyond national boundaries, and how the business world has shrunk, in ways even the most visionary people could have hardly imagined when the Plaza opened in 1907.” Of course, the Plaza had long welcomed foreign guests and was a favorite of visiting dignitaries. But the acquisition of the hotel by the Singaporean billionaire and the Saudi prince indicated an increasing globalization of the real estate market. It was a trend that would only accelerate in future years across Manhattan and at the Plaza itself.

A few years after Kwek and Alwaleed bought the hotel, they sold it to an Israeli condominium developer who carved much of the building into apartments. He then sold the remaining boutique hotel to an Indian tycoon. Last year, the hotel changed hands once more when the government of Qatar bought it.

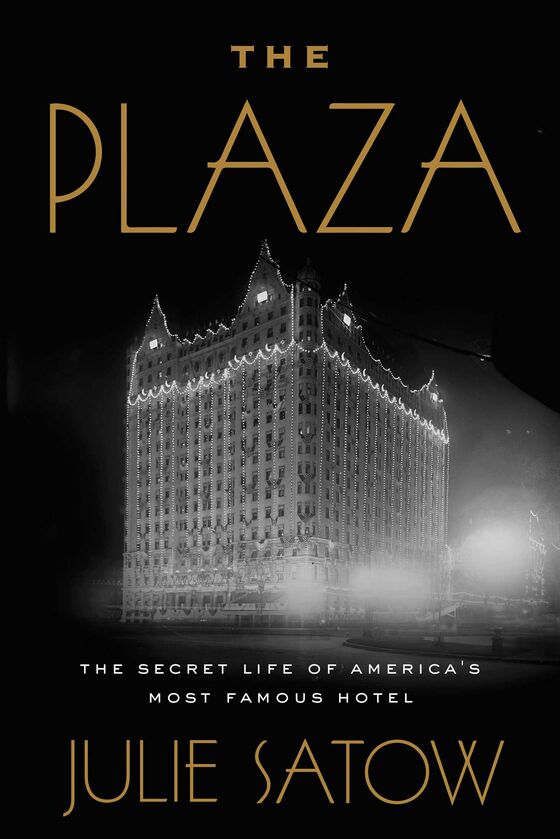

Adapted from The Plaza: The Secret Life of America’s Most Famous Hotel by Julie Satow, to be published on June 4 by Twelve, an imprint of Hachette Book Group. Copyright 2019 by Julie Satow

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Bret Begun at bbegun@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.