Target-Date Funds Held a Nasty Surprise for Retirees

Target-Date Funds Held a Nasty Surprise for Retirees

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- As the bull market soared, investors in America’s 401(k) retirement plans increasingly entrusted their savings to a one-stop kind of investment. All they had to do was pick a fund that corresponded with their retirement date. Presto, they had an age-appropriate mix of stocks and bonds.

These so-called target-date funds hold $1.4 trillion, equal to a quarter of the money in 401(k)s. The offerings generally place 20-year-olds mostly in stocks and then glide gradually into bonds as clients near their departure from the workforce. In theory, that strategy should protect older investors from the worst of bear markets—like the one sparked by the coronavirus pandemic.

But those who’ve just reached retirement may be in for a nasty surprise. These supposedly sensible target-date funds can be quite aggressive. Under a time-honored rule of thumb—albeit one many think is out of date—the percentage you hold in bonds should equal your age. By that approach, a 65-year-old would have only 35% in stocks.

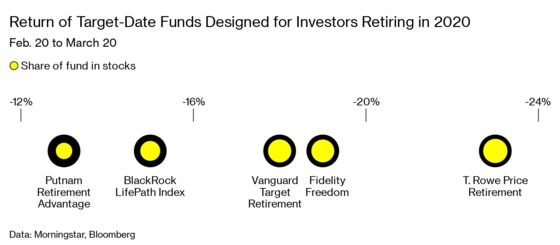

The three biggest providers of target-date funds bet way more on the market. For investors retiring this year, Vanguard Group and Fidelity Investments put roughly half in stocks; T. Rowe Price’s main target-date fund for that age is 55% equities. Some other fund companies had lower exposure. For many people, their retirement plan’s choice of target-date fund will determine how much risk they’re taking.

Being aggressive during the coronavirus-related market plunge smarted. From Feb. 20 to March 20, Vanguard, Fidelity, and T. Rowe Price, which together manage 69% of all target-date assets, had among the steepest losses for portfolios geared toward 65-year-olds, according to fund tracker Morningstar Inc. An investor in T. Rowe Price’s Retirement 2020 Fund lost 23%; the other firms’ customers weren’t far behind.

“People have been exposed to far more risk than they realize,” says Zvi Bodie, a Boston University professor emeritus who consults for Dimensional Fund Advisors, which offers target-date funds. “If you are retiring now, you are screwed.” James Veneruso of investment consultant Callan LLC says fund companies increased stock exposure in target-date funds during the bull market, in part because higher returns attracted more business. He predicts “the same hand-wringing and gnashing of teeth” that followed the last financial crisis over such allocations.

Fidelity, Vanguard, and T. Rowe Price representatives say their asset allocation reflects a prudent balance of protecting nest eggs while providing for needed growth over what could be decades of retirement. The companies consider these funds long-term investments, and, in general, more aggressive funds have posted higher returns over the decade. For example, the T. Rowe Price Retirement 2020 Fund’s ten-year return of 6.5% beat 95% of similar funds, according to Morningstar. Vanguard beat 91%, and Fidelity’s Freedom fund, 51%. “People are living longer than a generation ago and are more reliant on savings in 401(k) plans and what they get from Social Security,” says Joe Martel, a T. Rowe Price target-date portfolio specialist. Stocks have also rallied in recent days, paring back those steep losses.

Still, other investment firms are more cautious. The reason: While markets tend to recover, timing matters. Those who enter a bear market early in retirement may end up selling off their investments when they’re beaten down to meet income needs. Putnam Investments, for example, has less than a third of its Putnam Retirement Advantage 2020 fund in equities. As a result, the fund fell less than 13% from Feb. 20 to March 20. “When you lock in losses early in retirement, that gets magnified all of the way through,” says Brett Goldstein, a portfolio manager for the Putnam Retirement Advantage Funds. Similarly conservative funds from John Hancock Investment Management and BlackRock Inc. held up well, too.

Target-date funds, born in the 1990s, took off after 2006, when Congress passed a law encouraging employers to sign up workers automatically in 401(k)s. It also let companies pick a default option, and target-date funds were among the few allowed. Two years later, in the financial crisis, the funds geared toward older investors suffered big hits because of their heavy stock holdings, sparking congressional hearings. As the market recovered, they’ve became more popular than ever.

Target-date funds were designed to prevent classic investment mistakes, such as piling into funds with the strongest recent performance or being too conservative when young and too aggressive in retirement. A new kind of advisory service, relying on automated recommendations, uses a similar approach. Like target-date funds, so-called robo-advisers such as Betterment LLC rely on research that recommends investors shift from stocks to bonds over time, while retaining a healthy chunk of stocks at retirement.

Some financial scholars have found shortcomings in the assumptions behind target-date funds, particularly in the way they can be one-size-fits-all. In their view, investors need to consider individual circumstances such as the stability of their career and their health and wealth. “If you are a retiree in a 2020 target-date fund, and you and your spouse have a guaranteed pension, then maybe there is nothing wrong with having 50% or 60% in stocks,” says Moshe Milevsky, a professor of finance at York University in Toronto. “If you are retiring and all you have is a 401(k), then you shouldn’t have a lot of equity.” For investors concerned about running out of money, Milevsky likes immediate annuities, insurance products that provide a guaranteed lifetime income. (Milevsky has written nonacademic research paid for by financial firms, including insurers.)

Target-date funds aren’t the most aggressive retirement products. Billionaire money manager Ken Fisher has long said many retirees should put as much as 100% of their money in stocks. Otherwise, they risk running out of money over a decades-long retirement.

After the 2008 financial crisis, Fisher Investments faced at least a dozen legal claims from retirees with aggressive portfolios. In some cases, the firm successfully argued that clients would have been fine if they’d held on through the downturn. Spokesman John Dillard says the company’s Global Total Return strategy fell as much as 32% during the recent crisis but is now down 16% this year, through April 6, which is a smaller loss than its benchmark. “Clients of all types who have been with us are nicely ahead over the last few years or longer in an absolute and relative sense,” he says.

Last month, Fisher sent a letter to clients: “The best thing to do in moments of extreme panic is sit tight.” Raymond Runquist, a client who’s 76, is doing that for now. The retired Dallas engineer is nearly all in stocks and avoids checking how much he’s lost. “I’m going to stay the course,” he says. “I have lived through other ups and downs.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.