Taking Walgreens Private for $70 Billion Is Pricey Even for KKR

Taking Walgreens Private for $70 Billion Is Pricey Even for KKR

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Stefano Pessina, chief executive officer of Walgreens Boots Alliance Inc., has long had an affinity for private equity. In 2007 he teamed up with the buyout giant KKR & Co. to take Britain’s biggest pharmacy chain, Alliance Boots Plc, private. That move, followed by further deals to fold it into U.S.-based Walgreens, was the genesis of the multinational drugstore company as it’s known today. Now, KKR and Pessina might be teaming up again—though many doubt a deal is possible this time around.

KKR formally approached Walgreens in November about taking the company private in what could be the biggest leveraged buyout in history. Pessina, Walgreens’ largest shareholder with a 16.25% stake valued at about $9 billion, is expected to be the crucial player in any deal.

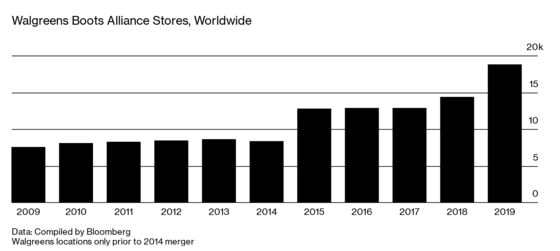

It’s not difficult to see why such a transaction might make sense for Pessina and Walgreens investors. The 118-year-old retailer is fighting to stay relevant at a time when Amazon.com Inc. and other online retailers are stealing customers for the household and beauty items in the front of its more than 9,000 U.S. stores—and pharmacy startups are coming for the prescription drug business at the back. Its plan to acquire rival Rite Aid Corp. was thwarted by regulatory concerns in 2017, and the company was forced to do a smaller store-purchase deal instead. Its shares had fallen about 30% from their 52-week high in December 2018 before Bloomberg News reported on the potential buyout on Nov. 5. “The retail pharmacy market is on the verge of an intense shakeout,” says Adam Fein, CEO of Drug Channels Institute, which researches the economics of pharmaceuticals. Over the next decade or so, the number of retail drugstore locations could decline by 10,000 or more, he says.

Depending on the price, going private could give shareholders a chance to sell at a premium. It may also give Walgreens time to make changes to adapt to the quickly shifting consumer landscape outside of the quarter-by-quarter demands of public shareholders. These changes could be painful for some. If a deal gets done, expect “significant layoffs and significant store closings” to improve the business, says John Coffee, director of the Center on Corporate Governance at Columbia Law School. In buyouts, he says, “the essential goal is to take the company into the machine shop for very substantial repairing and remodeling.” Because private equity deals are typically funded with debt taken on by the target company, a post-buyout Walgreens could still be under pressure.

For KKR the logic of a buyout is less straightforward, despite Walgreens’ decent cash flow. Start with the sheer size of the transaction, which analysts say could require at least $50 billion in debt financing and possibly more than $20 billion in equity. “It’s a huge stretch doing things over $50 billion,” said Stephen Schwarzman, head of KKR rival Blackstone Group Inc., at a Reuters event in New York. Most of the money would have to come from debt markets, where banks have struggled in recent months to find buyers for riskier buyout loans.

Most buyouts are funded with junk-grade debt. But to do a deal large enough to snag Walgreens, it’s likely some of the debt would be put together in a way that would earn it a better credit rating. “If you created an investment-grade tranche, you clearly increase the feasibility of the deal,” says Mark Vaselkiv, chief investment officer of fixed income at T. Rowe Price. “There would be a lot of demand.” A buyout investor might join with another firm or pension fund to raise equity.

Buyers could also split up U.S. and U.K. operations—the same ones put together in earlier deals—and sell the retailer’s stake in AmerisourceBergen Corp. Analysts say Walgreens’ holdings in the drug distributor could fetch more than $4.5 billion.

Still, the skeptics have been loud. “We believe the basic unattractive math of the transaction, not to mention the unattractive nature of the standalone pharmacy business, are high hurdles,” Deutsche Bank analysts wrote in a client note.

The main problem for Walgreens—the external threats facing the whole industry—isn’t something private equity can easily solve. The company is already cutting costs aggressively. So why is a deal under discussion? There’s a lot of investor cash—“dry powder” in private equity jargon—waiting to be put to work, which means even a complex transaction may be worth a look. As for Walgreens, the deal talk highlights the tough situation it’s in.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Pat Regnier at pregnier3@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.