The Supreme Court May Erode Decades of Wins for LGBT Worker Rights

The Supreme Court May Erode Decades of Wins for LGBT Worker Rights

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- For two decades, most of the LGBT movement’s highest-profile victories have come at the U.S. Supreme Court. In 2003 the justices issued a ruling legalizing gay sex that dissenting conservative Justice Antonin Scalia warned would set the stage for nationwide legalized gay marriage. Within 12 years, his prediction was realized. The court made marriage equality the law of the land—reflecting, and also accelerating, a sea change in straight Americans’ views and treatment of their LGBTQ family members and neighbors.

But next year the high court could deal LGBTQ people a painful blow: wiping out lower-court rulings that shield them from getting fired for who they are.

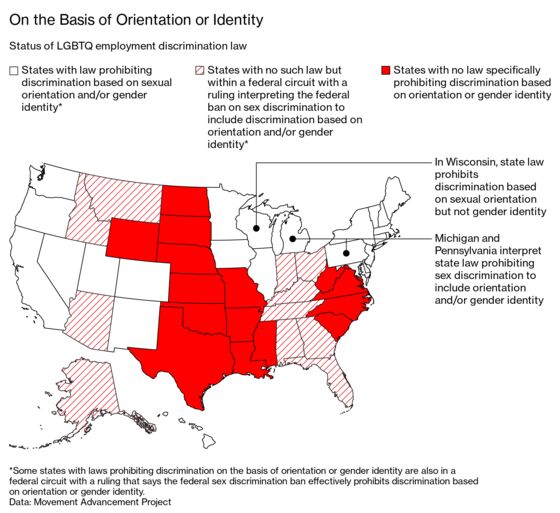

In a trio of cases this coming term—involving a child welfare worker, a skydiving instructor, and a funeral director—the Supreme Court will hear arguments on whether it’s legal for bosses to discriminate against LGBT employees. Contrary to what many Americans now assume, no federal law explicitly prohibits firing workers simply for being gay or transgender. Nor do the laws of most states—including some populous ones such as Texas and Ohio. (Only 21 states and Washington, D.C., have laws that explicitly prohibit private companies from firing workers for being gay or trans; another one restricts anti-gay firing but not anti-trans dismissals.)

Jimmie Beall learned that the hard way in 2003, when she was abruptly terminated from her position as a public school teacher in London, Ohio, a couple weeks after receiving a glowing evaluation. Beall, a lesbian who taught government to high schoolers, says she learned from local parents about rumors she was fired for being gay and was shocked to learn there was no law specifically prohibiting that. An email later surfaced from the superintendent to the school board alluding to Beall’s sexual orientation while discussing not bringing her back for another school year. “I thought, They can’t do that, because that would be illegal—there’s protection against discrimination,” says Beall. “It never occurred to me that there wasn’t.”

Despite the lack of explicit protection for LGBT workers, Beall filed a lawsuit arguing that because she was a public employee, firing her for her sexual orientation violated the Constitution. In 2006, after a new superintendent took over and a judge ruled Beall’s case could proceed, the school district agreed to settle the case and establish a nondiscrimination policy. But Beall says she assumed that before too long the state of Ohio or the federal government would prohibit anti-gay discrimination across the board. “I never imagined that, this many years later, we still would not have the same protections that everybody else already has.”

In recent years, some courts have ruled that the 1964 Civil Rights Act’s ban on sex discrimination also implicitly prohibits bias based on sexual orientation or gender identity. “When a male employee is fired because he has a husband, and he would not be fired if he were a woman who had a husband, then he was fired because of his sex,” says Jennifer Pizer, law and policy director for Lambda Legal Defense and Education Fund, a nonprofit that pursues LGBTQ civil rights cases. “When a trans woman was acceptable at work presenting as a man, but was fired when she presented her true gender, which is female, she was fired for being the wrong kind of woman.”

Citing past precedent that discrimination for not conforming to sex stereotypes is a form of illegal sex discrimination, several federal circuit courts have embraced such arguments, creating a patchwork of protections covering their jurisdictions. Next year the justices could either extend those protections nationwide or wipe them out. So in states that haven’t passed laws prohibiting anti-LGBT bias but have been covered by federal appeals court precedents restricting it—including Florida, Georgia, and Indiana—a Supreme Court ruling could give companies that don’t want LGBT people in the workplace a green light to fire them. “There won’t be a question mark anymore,” says Beall. “And because of that, I could see a whole lot more people discriminating.”

President Trump’s appointment of Justices Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh, which made the Supreme Court more conservative than it’s been in a generation, could turn the tide. “My instincts suggest that this is an uphill battle,” says Anthony Michael Kreis, a visiting professor at Chicago-Kent College of Law who’s helped draft pro-LGBT legislation. The prospect of a loss at the Supreme Court raises the stakes for action in Congress, where Democratic allies have tried unsuccessfully for decades to pass a law that would explicitly ban anti-LGBT bias. “I don’t have a lot of confidence that the court will protect LGBTQ Americans from discrimination,” says Rhode Island Democratic Representative David Cicilline.

On May 17 the House finally passed the Equality Act, a sweeping bill Cicilline sponsored that would beef up the Civil Rights Act by prohibiting sexual orientation and gender identity bias in employment, as well as in education, credit, federal programs, housing, jury service, and public accommodations such as hotels and restaurants—even if the Supreme Court rules that the original law didn’t do any of those things. The bill’s supporters include more than 200 large employers such as Amazon.com, Apple, Coca-Cola, and Marriott. Facebook Inc. Chief Operating Officer Sheryl Sandberg said in an online post that the legislation “is true to what we’ve always valued at Facebook for our employees and the people who use our products around the world. No one should face discrimination because of who they are—and we hope Congress passes this legislation.”

After proposing narrower bills and fighting among themselves on questions such as whether to pursue the rights of gay employees separately from those of trans workers, liberal lawmakers and activists unified in 2015 behind the more-ambitious Equality Act, which they say better highlights and addresses the full spectrum of discrimination LGBT people still face. In a survey this year by the Public Religion Research Institute, 69% of Americans—including majorities in all 50 states—expressed support for legislation protecting LGBT people in hiring, public accommodations, and housing.

But in Congress, like the Supreme Court, the fate of anti-discrimination protections now rests with conservatives. Republicans command a 53-47 majority in the Senate, and even if Democrats were to take back that chamber and the presidency, advancing the Equality Act would require either abolishing the Senate’s 60-vote filibuster rule or mustering enough GOP support to reach the 60 votes. The same day the Democratic-controlled House passed the Equality Act, Mike Lee, a Republican senator from Utah and a Judiciary Committee member, called it “counterproductive” legislation at a time when “Americans are becoming more tolerant every day” anyway. “It unnecessarily pits communities against each other and divides our nation when patience and understanding are so sorely needed,” he tweeted.

Conservative groups including the Heritage Foundation, the nonprofit that Trump said helped develop his roster of potential Supreme Court picks, are hoping LGBT activists get rebuffed by both the judiciary and the legislature. For the justices to rule that the Civil Rights Act already covers sexual orientation and gender identity “would be usurping the power of Congress,” says Emilie Kao, who directs Heritage’s Richard and Helen DeVos Center for Religion & Civil Society. If Congress did pass the Equality Act, she says, it could infringe on management prerogatives such as the ability to dictate what’s worn by an employee, including those who have “a belief that they are of the opposite sex.”

Oregon Democrat Jeff Merkley, who sponsored the Equality Act in the Senate and is working to secure GOP support, says he hopes the Supreme Court’s coming LGBT cases will help draw national attention to the bill: “The issue of having full opportunity in our society, of having full freedom, shouldn’t depend on the whims of a conservative court.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Ellis at jellis27@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.