Sunday Strategist: This $200,000 Grill Is a Masterpiece of Arbitrage

Sunday Strategist: This $200,000 Grill Is a Masterpiece of Arbitrage

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- In this week’s magazine, you’ll find a deep dive on Grillworks, a company that makes the uber expensive open-fire grills that are running white-hot in the restaurant industry.

It’s a family empire, the success of which is all the more improbable because the Grillworks clan—the Eisendraths—are short on both business chops and entrepreneurial drive. Charles, the patriarch and Grillworks founder, was a foreign correspondent for Time magazine. Ben, his son and current Grillworks chief, studied environmental science in his former life and built digital products for AOL.

Perhaps unwittingly, the Eisendraths executed a masterstroke of arbitrage twice over. First, the elder Eisendrath spotted the idea when based in Buenos Aires, where most households cobble together a fire-burning mechanism known as a parrilla. He figured something like this would go over pretty well in the States. (Granted, this is the basis of virtually all international expansion, but what’s interesting is that it was an arbitrage of culture, not finance, and it's happening more these days, trade wars be damned.)

Americans, for example, have developed a taste for Korean cosmetics, with its strange ingredients, like snail slime and bee venom. Meanwhile, Netflix has figured out that those same consumers have an appetite for dramas and murder mysteries set and produced in foreign markets, Japan’s Atelier, Dark in Germany and Israel’s Fauda, to name a few.

Grillworks worked some magic on the supply side as well. While teaching at the University of Michigan, the elder Eisendrath found some uncommonly skilled and relatively underemployed metalworkers, primarily castoffs and retirees from Detroit’s auto industry. When the younger Eisendrath brought the company back to life a decade later, he moved production back to Michigan, near a little town about four hours north of Detroit where a couple dozen people were refurbishing classic cars. The arrangement is fairly inconvenient, but the quality and price are hard to beat. And the economics still aren’t great on shipping an 8,000-pound machine from Asia.

This kind of labor arbitrage, of course, is why Boeing builds airplane fuselages in Charleston, S.C. and Mercedes bolts its sedans together in Alabama. It’s standard blocking and tackling for a massive, incumbent global business. However, the Grillworks story shows that a geographically flexible approach to human capital can make the difference in whether a young company or product line gets off the ground in the first place.

American Giant, for example, found factories-worth of high-skilled, underworked apparel wizards in the Carolinas, the hollowed out heart of America’s once-mighty textile industry. The arrangement made the math work on its seminal shirts and has since allowed the company to start making jeans and a bunch of other products they may not have otherwise considered.

“We can't make a flannel shirt in America?” founder Bayard Winthrop told The New York Times recently. “I’m not going to accept that answer.”

As for Grillworks, its food forges are catching fire abroad. Eisendrath’s next challenge: selling them in Argentina.

Businessweek and Beyond

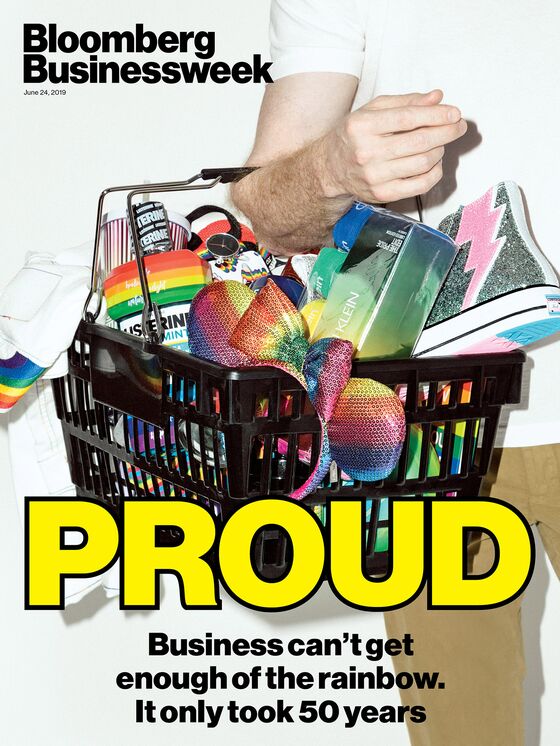

- Come out come out wherever you are

- From algorithms to lab animals, a new Silicon Valley pivot

- When your CEO is on Everest, does risk still equal reward?

- “There are banks that are screwed and there are banks that don’t know they’re screwed.”

- Trademarks are tough ... even for Adidas

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Silvia Killingsworth at skillingswo2@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.