Roku Built the Dominant Streaming Box. Now It’s Under Siege

Roku Built the Dominant Streaming Box. Now It’s Under Siege

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- More than 30 million people use a Roku device to navigate the constellation of streaming TV services. The company’s portfolio includes the “stick” ($49.99), which resembles a USB drive; the “puck” ($79.99), a black square with smooth edges and minimal detailing; and a $400 smart TV with Roku Inc.’s operating system. The more expensive options offer better image quality and such features as extra digital storage space.

As the era of cable and satellite TV dims, Chief Executive Officer Anthony Wood says Roku is poised to keep capitalizing on the boom in streaming video. It’s an independent player that can work well with all the entrants, he says, including new services from Disney and Apple and forthcoming ones from AT&T and Comcast. “It’s satisfying to see the world be all in on streaming,” says Wood. “That’s nothing but excellent for Roku.” Many investors on Wall Street agree: The company’s stock is up more than 300% this year, and Roku is valued at over $17 billion.

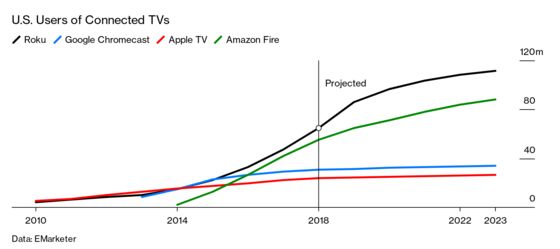

Having built the dominant box, Roku is under siege from companies that recognize the value of its business model. Google sells a competing smart TV operating system. Samsung sells more than a dozen smart TVs that don’t use Roku’s operating system. Comcast Corp. is giving its internet subscribers a free streaming box. AT&T Inc. is offering a box for its customers. Apple Inc. is investing billions in streaming shows designed in part to strengthen the appeal of its hardware. But Roku’s biggest challenger is Amazon.com Inc., which is vying for tie-in deals for its Fire TV with smart TV manufacturers and battling for supremacy in international markets. In September it announced a major expansion in Europe, where Roku is less dominant.

Escalating competition, along with uncertain future growth, has raised investor concern. In early December, Roku shares fell as much as 17% after a Morgan Stanley analyst suggested the stock was overpriced because of “exuberance over all things streaming” and warned that its revenue and profit growth may “slow meaningfully” in 2020. Other analysts challenged that assessment.

For now, Roku enjoys a sizable lead in the U.S., at least in part because it had a head start. Wood founded Roku in 2002; several years later he joined Netflix Inc. to help build its first piece of streaming hardware. In 2007 the product was ready. But at the last minute, Netflix CEO Reed Hastings decided that for his streaming service to succeed, it needed to be on every device, not just Netflix’s. That winter, Hastings spun off the streaming technology to Roku and invested $8 million in Wood’s company.

Over the next decade, Roku forged partnerships with nascent streaming services and cemented its position atop the emerging landscape of home entertainment. Last year the company generated $742.5 million in revenue, up from $513 million in 2017. In the latest quarter, Roku devices accounted for 44% of all connected-TV viewing hours, while Amazon’s Fire TV was second with 20%, according to industry analytics firm Conviva Inc.

Even so, Roku still loses money. The company makes almost no profit from selling devices. It keeps prices low to attract users, whose viewing habits it sells to advertisers. That’s where the real growth potential is: According toEMarketer Inc., ad spending on connected TVs—in-stream ads or ads on menus—will grow to almost $7 billion by the end of 2019, up about 38% over the past year, and is expected to top $10 billion by 2021.

Nearly every inch of real estate on Roku is for rent. For $1 million, a streaming service can take over the home screen to advertise a show. When Hulu got the rights to stream Seinfeld, it paid Roku to transform a portion of the screen into an image of Jerry’s apartment instead of the default purple backdrop. Hulu, Netflix, Showtime, and YouTube have paid Roku to build brand-specific buttons on its remote controls; these lead users straight to those services. At $1 per customer for each button, the cost can quickly add up to millions of dollars in monthly fees.

Roku’s large base of cord cutters gives it leverage over any media company that wants to woo subscribers. Historically, cable- and satellite-TV distributors have paid media companies to carry their networks and received, in return, a slice of their advertising inventory. Roku doesn’t pay anything to the channels it distributes, yet it still takes a share of their ad revenue.

Roku also signs short-term deals with streaming networks, enabling it to renegotiate (read: ask for more money) quickly. Just months after signing a new contract, Roku executives will threaten to cancel a channel if its owner doesn’t give Roku a larger cut of ad sales, say several people familiar with negotiations who asked to remain anonymous to avoid upsetting their relationships with the company. In 2016, Roku told executives at Vevo LLC that if it didn’t share its ad revenue, it couldn’t be on Roku, according to Variety. Eventually, Roku relented; most services don’t have Vevo’s scale. “Distribution agreements expire, and if one isn’t in place then a channel could come out of the Channel Store,” the company said in a statement. “As our scale grows, so does our ability to help channels reach an audience and monetize, so of course we want to be properly compensated.”

Wood says there’s enough advertising dollars shifting from TV to online video for everyone to share in the riches. Roku now has a slice of the ad inventory of the vast majority of streaming services and commands some of the highest rates in the media industry, bringing in about $30 per 1,000 viewers. The company can justify higher rates in part because its software is embedded in one-third of all smart TVs sold in the U.S. When a smart TV runs on its software, Roku is the first thing a consumer sees when she turns on the TV.

Two years ago, Roku introduced its own network, the Roku Channel, which offers old movies and TV reruns. It’s free and supported by commercials, giving Roku even more ad inventory. The company also operates a digital store that lets customers sign up for ad-free services such as Netflix; each time Roku facilitates a sale, it takes a cut.

To lure Roku’s customers, its rivals will continue to test out a variety of tactics, including lower prices (Google), aggressive retail promotion (Amazon), and a less cluttered user experience (Apple). For its part, Roku will keep building on its advantage with TV manufacturers and positioning itself as the easiest brand to use.

Meanwhile, Roku’s ad revenue is expected to top $600 million this year and could reach $1.5 billion by 2022, says RBC Capital Markets analyst Mark Mahaney. Sam Bloom, the head of advertising firm Camelot, whose clients include Nordstrom Inc. and Whole Foods Market Inc., says: “When we went out to Roku, my eyes were opened. I was shocked by how large the footprint is there.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Bret Begun at bbegun@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.