Wall Street Loves China More Than Ever

Wall Street Loves China More Than Ever

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- As tensions were rising between the U.S. and China last summer, the chief executive officer of JPMorgan Chase & Co. was letting it be known that he wanted to get to Hong Kong as soon as he could. Jamie Dimon did just that in November, becoming the first major U.S. bank executive to visit Greater China since the pandemic began. His 32-hour trip to the Asian financial hub was billed as a chance to thank thousands of employees there. But it was also a reminder of the company’s commitment to the territory, as well as to mainland China, where JPMorgan has exposure of about $20 billion, mainly from lending, deposits, trading, and investments.

Some U.S. politicians have been calling for companies to back away from China, over concerns about national security and human rights. But Wall Street banks are instead deepening their ties. JPMorgan in August took full control of a securities joint venture with a Chinese company, and now wants to do the same with an asset management business it partly owns. Morgan Stanley is seeking five new banking licenses in mainland China in 2022, while Goldman Sachs Group Inc. has been doubling its workforce. Citigroup Inc. applied in December for a securities trading and investment banking permit and plans to seek a futures license in 2022, adding 100 employees in the country in all.

Both the U.S. and Chinese governments have cracked down on Chinese companies listing their shares in New York, hurting a lucrative business that was driven from Hong Kong. But U.S. banks that want a piece of the world’s second-largest economy—and second-biggest issuer of equities—are shifting gears to take on China’s top lenders on their own turf. “I don’t think we have a choice,” says Gokul Laroia, CEO of Morgan Stanley’s Asia-Pacific operations, describing the bank’s decision to think of China as one big opportunity and to compete for business on the mainland as well as offshore. Even though global banks haven’t made much money in China yet, the potential upside is massive, he says: “If you keep saying I am not going to invest in the domestic platforms because they are not as profitable, I think you’re missing a trick.”

Wall Street has long eyed China as the last great moneymaking frontier, and 2021 was supposed to be the year companies’ vast investments would start to bear fruit. Foreign banks had just been given the right to take full control of their joint ventures and set up their own asset management businesses. But before the year even began, Beijing scrapped Ant Group Co.’s $35 billion initial public offering at the last minute, depriving firms including JPMorgan and Citigroup of almost $400 million in fees. Then a regulatory squeeze on sectors from technology to education and property curbed demand for IPOs.

In addition, the U.S. is strengthening financial disclosure rules for Chinese companies listing shares on American exchanges. China’s policymakers are forcing ride-hailing company DiDi Global Inc. to delist in the U.S., citing concerns about control over company data, and are tightening a loophole that’s facilitated dozens of U.S. IPOs. The result: a 52% drop in listings by value of Chinese companies in 2021, cutting fees for banks such as Goldman that took DiDi and other companies public in New York. That business had been so strong that banks tallied more than $1 billion in IPO fees in 2020 from Chinese companies listing in the U.S., before slumping 42% last year to $625 million.

While the New York freeze may be temporary, it’s becoming clear that Chinese companies have less need to raise money abroad when they can easily list in Hong Kong or via the growing exchanges in Shanghai or Shenzhen. Peter Alexander, who’s been advising global asset managers in China for almost two decades, says a senior China official recently made that point to him: “He said, ‘Peter, tell your clients we will more than welcome their capital, but we no longer need their capital markets.’”

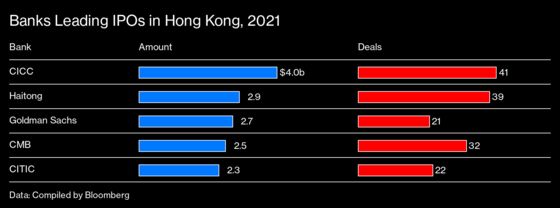

Moving further into China’s domestic market is fraught with risk. State-owned brokerages have extensive teams on the ground doing deals with established Chinese companies and startups. Global financial firms posted a combined loss in the mainland of $48 million in 2020, compared with $24.4 billion in profits at China’s investment banks, according to filings.

A look at dealmaking rankings shows foreign banks haven’t made significant inroads in China after years of trying. Goldman ranked 15th in domestic Chinese equity-raising last year, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. Foreign banks have never cracked the local bond market, though they do better for China mergers and acquisitions, with five in the top 10 for 2021. “None of these companies really have anything to offer China” in the local market, says Dick Bove, an analyst at Odeon Capital Group who’s been covering Wall Street for decades and cites the league tables as evidence. “They learned everything the American banks had to teach about how to run an investment banking operation, and now they don’t need them.”

Global bankers say they’re just getting started with new licenses to expand on their own after decades with local partners, and that gaining just a fraction of the $45 trillion market would lead to windfalls. They also say that with more money flowing into China, trading and asset management will be huge growth areas. Foreign purchases of Chinese stocks on the mainland accounted for 15% of the total flows in the third quarter, up from just 3% in 2013, according to Morgan Stanley. Global banks and money managers could eventually take 10% of the mutual fund market in China over five years, says Jasper Yip at Oliver Wyman in Hong Kong.

Despite all this potential, U.S. financial companies are taking heat over China at home. Utah Senator Mitt Romney has called hedge fund billionaire Ray Dalio’s investments in China “a sad moral lapse,” while Florida Senator Rick Scott accused bankers of placing profits above human rights. “This modern gold rush into China by the big Wall Street banks in hopes of fat profits raises numerous concerns,” says Mark Williams, a professor at Boston University and former Federal Reserve bank examiner. “Growing U.S. tensions with China has increased political risk and the likelihood of trade sanctions and abrupt policy changes that could halt planned expansion.”

Wall Street remains undaunted, and Dimon’s not the only CEO who’s been eager to get on a plane: David Solomon of Goldman Sachs has been saying he’ll go to the country as soon as it’s allowed, according to people familiar with the matter. “Given the important position that China plays economically in the world, you can’t be Goldman Sachs without participating in that,” Solomon said at the Bloomberg New Economy Forum in Singapore last November. He said there’s been no direct pressure on the bank to alter course in China, though that could change. “But we think about this with a 10-, 20-, 30-year perspective, not with the next couple of years.’’ Solomon was among almost 30 business leaders who participated in a one-hour video call on Dec. 15 with Premier Li Keqiang to discuss a range of topics including China's reopening plans, according to one person with knowledge of the meeting.

Recent Goldman Sachs deals in China include its participation in the $4 billion Shanghai IPO of BeiGene Ltd., a biotech company—its first co-invested deal on China's technology stock board. And after a 17-year wait, the bank now owns its securities business in China. That gives it free rein to pursue a growth strategy that includes doubling its workforce to 600 and ramping up in asset management, which President John Waldron has called the “biggest opportunity” in China.

Global asset managers are joining the push into China’s 24.4 trillion-yuan ($3.8 trillion) mutual fund market. BlackRock Inc. raised $1 billion in September for its first China fund, while Paris-based Amundi SA aims to double assets under management in the Greater China area—including Hong Kong and Taiwan—to $250 billion by 2025. Beijing’s push to steer individuals away from property investment will give an additional boost to these funds, says Xiaofeng Zhong, the company’s chairman for the region. Still, not all big money managers are enthusiastic about their chances: Vanguard Group Inc. scrapped its plans to apply for a fund license last year. “China has become an extremely difficult business opportunity to navigate,” says Alexander, the consultant to fund companies, who is managing director at Z-Ben Advisors Ltd. in Shanghai.

Morgan Stanley had been more cautious in the mainland market than some rivals, but it boosted stakes in its joint-venture securities business to almost 100% in 2021, and Laroia says it plans to apply for futures, derivatives, brokerage, research, and market-making licenses in 2022. Among other things, Morgan Stanley intends to provide foreign exchange and interest rate hedging services, along with market-making for international and domestic institutional clients in stocks and bonds.

JPMorgan, meanwhile, became the first foreign bank to take full control of its securities unit in China last year as part of its broader push into the country. “If we have the licenses and we control them, then the business will come,” says Filippo Gori, the bank’s CEO for Asia-Pacific. “You need all the cylinders to fire to make it work. It’s not a single-business strategy.”

The bank has been charging ahead ever since Dimon—who joked in November that his bank will outlast the Chinese Communist Party, before walking back his remarks—gathered executives in Hong Kong in 2016. He told them he envisioned an office in China that matched the bank’s tower in New York, according to people familiar with the matter. That hasn’t happened yet. But after the bank won approval to buy its securities partner, Dimon said, “China represents one of the largest opportunities in the world for many of our clients and for JPMorgan.” —With Dingmin Zhang and Sridhar Natarajan

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.