One Trader Calls All the Shots in the Treasury Bond Market

One Trader Calls All the Shots in the Treasury Bond Market

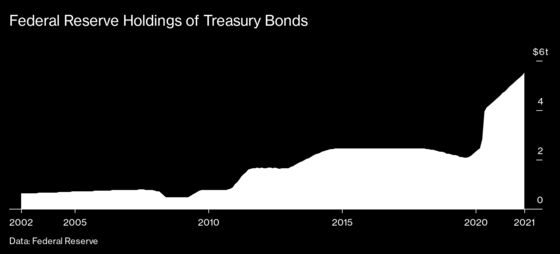

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- At 10:10 a.m. most work days on Wall Street, officials at the Federal Reserve wade into the Treasury bond market. For the next 20 minutes, they proceed to snap up bonds of all shapes and sizes. They’re impervious to price moves, and they never sell. An indiscriminate bond-buying machine, they’ve now amassed a $5.5 trillion stockpile of the debt.

This is a staggering sum, equal to more than 10 times the amount the Fed owned before the Great Recession and quadruple the amount held by any other investor. All of this buying comes in the name of injecting money into the economy and driving down interest rates to ward off collapse, first in 2009 and again after the pandemic hit. Which is a reasonable and noble endeavor—central bankers all over the world have pursued similar policies—but in the process, the Fed has come to dominate the bond market to such a degree that no other voice seems to matter nowadays.

At less than 1.6%, the yield on the 10-year Treasury bond, a key benchmark for borrowing costs across the globe, is detached from reality. The U.S. economy is growing at a clip of almost 6% this year, inflation is running above 5%, and the Biden administration posted a budget deficit of more than 13% of gross domestic product. The only bigger deficit recorded in the past seven decades was the one the Trump administration delivered last year.

The bond traders of yesteryear would never have accepted such a paltry return in this kind of environment. In the 1980s, as the U.S. was coming out of a prolonged bout of unusually high inflation, they earned the moniker “bond vigilantes” for the way they’d react to any sign of incipient inflation by selling bonds and driving up interest rates. Tom Wolfe ironically dubbed them Masters of the Universe in The Bonfire of the Vanities, while Michael Lewis turned them into cult heroes in Liar’s Poker.

The vigilantes caused a stir in Washington a few years later when they dumped bonds at such a frenetic pace—triggering a huge surge in government borrowing costs—that they bullied the Clinton administration into overhauling its budget plans. The episode so shocked the president’s political adviser, James Carville, that he famously quipped at the time that he wanted to be reincarnated as the bond market, because “you can intimidate everybody.”

That moment turned out to be the high point of the vigilantes’ power. Slowly and steadily, they’ve lost influence to the point that today they find themselves “outgunned by the bond pacifists” at the Fed, says Jared Gross, head of institutional portfolio strategy at JPMorgan Asset Management.

This creates a risk for the economy. The bond market, for all its imperfections, acted as an important check on government fiscal and monetary excesses. That power now rests almost exclusively with Fed Chair Jay Powell—the man who, along with his fellow board members, tells the Fed’s traders how many bonds to purchase each day.

So there’s a lot riding on Powell’s gamble that the surge in inflation is just a temporary, Covid-induced phenomenon that will soon fade. The danger is that if he’s wrong and inflation becomes entrenched in coming months, he’ll need to reverse policy so suddenly and aggressively that he could snuff out the economic recovery.

Vineer Bhansali, the founder of LongTail Alpha, an asset management firm in Newport Beach, Calif., says pension fund managers have started asking him for guidance on how to best protect their portfolios against interest-rate volatility. “That tells you they are getting worried,” he says. At some point, he adds, “markets are just going to break in some parts. It will be a fun time to trade.”

Now is decidedly not.

The bond market on many days is stable to the point of appearing comatose. The ICE BofA Move Index, which measures investors’ expectations for bond price swings, hit an all-time low last year; it’s picked up some since then, but the moves remain small when observed from almost any historical perspective. The old guard on trading desks chuckles at how the younger generation got riled up when yields crept up 30 basis points, or 0.3 percentage point, in recent weeks. In the 1980s and 1990s, the market moved that much in a day or two.

“It’s funny,” says John Kerschner, who began working in financial markets in 1990 and today oversees U.S. securitized products at Janus Henderson Investors. “People forget. You had rates going up and down many hundreds of basis points. The Treasury market was a different beast back then.”

Or, as Marty Mitchell, a contemporary of Kerschner’s, puts it, “the game isn’t as sexy as it used to be.” Mitchell traded bonds for decades at several different shops and then in 2014 started a popular daily strategy note, the Mitchell Market Report. He shut it down last year after the Fed started to dominate the action. “Trading opportunities have diminished quite a lot,” says Mitchell, 58. “My expertise was no longer needed.” He’s out of the bond business entirely now and spends his days working on a book about Jesus Christ.

It isn’t just the Fed—other forces are working to suck volatility out of the market and hold down yields. The rise of automated trading and passive investing, which strip much of the opportunistic buying and selling out of the marketplace, has played a big role. That benchmark rates are even lower in many other developed countries also means U.S. bonds don’t have a lot of competition. Treasuries “are the global safe-haven debt of the world. There is nowhere else to go,” says Margaret Kerins, head of fixed-income strategy at BMO Capital Markets. “So this is part of it, too.”

Still, the Fed is the dominant reason. Even the recent uptick in yields highlights this: It all began as a reaction to Powell stating publicly for the first time that he and the Fed board were getting ready to pare their bond purchases from the current pace of $80 billion a month. (The official beginning of that paring, or tapering in market parlance, could come at a policy meeting on Wednesday.) It was a clear sign that Powell wanted yields to start slowly moving higher.

The vigilantes obliged. For now at least, they do as he wishes.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.