States Are Outrunning the Feds in Responding to Coronavirus

States Are Outrunning the Feds in Responding to Coronavirus

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- On March 9, as President Donald Trump was downplaying the health risks posed by the coronavirus and comparing it to the flu in an effort to keep stocks from tumbling, Ohio Governor Mike DeWine was declaring a state of emergency—even though the state had only three confirmed cases at that point—warning Ohioans that more stringent safeguards were on the way.

The same day in California, Governor Gavin Newsom was overseeing a plan with Oakland Mayor Libby Schaaf to disembark, treat, and quarantine passengers from the virus-stricken Grand Princess cruise ship. And in Washington, the state with the highest number of Covid-19 deaths, Governor Jay Inslee was weighing mandatory limits on public gatherings, after successfully petitioning the legislature for $100 million in emergency funds.

The coronavirus pandemic has exposed a stark divide in the U.S. between the state and federal responses to the crisis, with governors stepping into a void left by the sluggish actions and mixed messaging of the federal government. It’s a division that Trump himself has deepened, say local leaders of both parties and political observers—for example, by telling governors on a teleconference that they should try to obtain ventilators and other medical equipment on their own.

“Normally, if you’re a governor, you would wait for some lead from the federal government,” says Raphael Sonenshein, a political science professor at California State University at Los Angeles. “You would expect the national government to come in with the big checkbook and the sweeping powers it possesses. When the national government doesn’t play that role, you see governors stepping into the vacuum.”

The federal government responded to the outbreak weeks later than other countries, especially in calling for social distancing and making testing available so the spread of the virus can be understood and limited, says Dr. Peter Katona, professor of medicine and public health at the University of California at Los Angeles. States and their leaders have wide latitude to take action during a public-health crisis, and in this instance, they’ve been forced to be especially aggressive, he says. “To be blunt, it’s because the White House really has not been doing things correctly,” Katona says. “The federal government has just been very, very slow in acting on this in an appropriate way.”

In early March, much of what the president said about the virus was contradicted or clarified by other administration officials, including his assertion that the number of cases nationally was declining and that “anyone who wants a test can get a test.” The president unleashed broadsides at press conferences and on Twitter, calling Inslee “a snake” while defending his administration’s response to the crisis and attacking the news media’s coverage of it. But on March 13 the White House declared a national emergency, freeing up billions of federal dollars to assist state and local governments. A few days later, Trump seemed to shift his tone on the virus, calling for people to avoid large gatherings and admitting, “This is a very bad one.”

According to polls, Americans view the outbreak and government response through a partisan lens, with most Republicans saying Trump has done a good job handling the crisis, while most Democrats say he hasn’t. Some Republican governors have been slow to respond—possibly, Katona says, because they took their cues from Trump. Oklahoma Governor Kevin Stitt, for instance, drew criticism for a March 14 selfie he tweeted and later deleted, showing himself and his children at an Oklahoma City food hall and saying, “It’s packed tonight!”

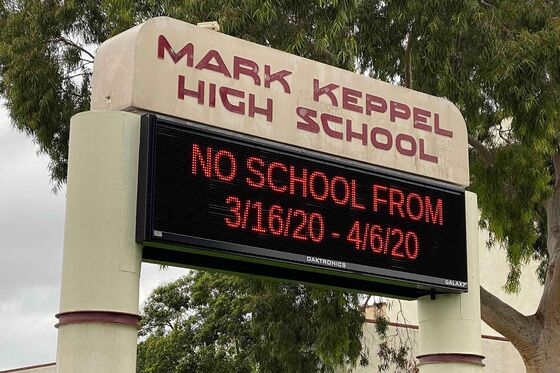

Other Republican governors, including DeWine, Charlie Baker of Massachusetts, and Gary Herbert of Utah, have been among those taking the strongest steps to counter the outbreak. DeWine has been more active and forceful than most. A day after his emergency declaration, DeWine recommended that spectators be banned from indoor sporting events—before leagues began canceling games. He set the limit of mass gatherings at 100 when others put the number higher, and he was one of the first governors to close schools, bars, and restaurants.

DeWine also supported the state health director ordering the polls closed in the March 17 primary as a health emergency. The governor said all along he based his decisions on science and guidance from a team of health experts, erring on the side of being too aggressive in the name of saving lives. If they have made mistakes, it will be because they “were too cautious,” DeWine told reporters on March 11. “But I don’t think these are mistakes. We’re doing what we have to do.”

DeWine’s actions have drawn praise from Democrats, including former Ohio Governor Ted Strickland, who says he disagrees with DeWine on some social issues but thinks he’s handling the crisis well. “He’s providing the kind of leadership that probably we needed at the federal level,” Strickland says.

In California, as Newsom declared a state of emergency, moved to limit public gatherings, and tried to obtain more tests to screen for the virus, he worked with Oakland’s Schaaf, a fellow Democrat, to find a place to dock the Grand Princess after other mayors expressed concern that the ship’s passengers might spread the virus to their cities. “We have to not let our fears impede our humanity,” Schaaf said.

The plan provided for the ship to dock at an empty industrial berth and most of its California passengers to be quarantined for 14 days at military bases. Others with the disease were treated at local hospitals, and passengers from outside the U.S. took chartered flights back to their home countries.

Trump’s criticism of Inslee came after a tweet from the Democratic governor in February in which Inslee said he’d spoken with Vice President Mike Pence—who’s heading the White House coronavirus response—and asked that the administration stick to facts when discussing the crisis. Inslee brushed off Trump’s “snake” insult in an appearance on CBS, praising the help he said Pence and the federal government had given him in battling the contagion. “We are very pleased with the federal government helping us right now,” Inslee said. “I don’t care what Donald Trump thinks of me, and I just kind of ignore it.”

The U.S. federalist system of government, intended to allow the national and state governments to share power, is often a source of tension as leaders assert the primacy of federal over state authority on particular issues, or vice versa. The system appears to rule out the sort of unilateral actions taken in response to the coronavirus by countries such as China—which isolated an entire province to fight the outbreak—and France, which imposed a near-total nationwide lockdown. Experts say the limits of U.S. federal power in taking extraordinary steps to deal with a public-health crisis haven’t been thoroughly tested.

Other countries’ experience in fighting the outbreak shows that speed matters, with cases of Covid-19 expected to double every several days if there’s no intervention. So states should be taking aggressive actions, says Rajeev Venkayya, who was responsible for the development and implementation of the National Strategy for Pandemic Influenza under President George W. Bush. When it comes to measures like staying home and closing schools, “we have to do them early and in a coordinated fashion for them to [be] maximally effective, which makes leadership from government critically important,” Venkayya says. Governors acting on their own create a patchwork of safeguards across the U.S. “You’d like to see every state taking some form of action because this is a global problem, and not a problem in one state or one city or one county,” says Katona.

New York’s Andrew Cuomo declared a state of emergency on March 7, and three days later deployed National Guard troops to assist with more than 100 confirmed cases at the time. On March 12, he banned gatherings of more than 500 people. That meant closing down Broadway shows—a $1.8 billion annual industry—as well as museums and other cultural sites. On March 16, Cuomo joined New Jersey Governor Phil Murphy and Connecticut Governor Ned Lamont, both fellow Democrats, to announce a ban on crowds of more than 50 and ordered closure of bars, movie theaters, restaurants, and gyms. The decision to act jointly came “amid a lack of federal direction,” according to a statement from the governors.

Trump fired back at Cuomo after the day’s teleconference, tweeting: “Just had a very good tele-conference with Nations’s Governors. Went very well. Cuomo of New York has to ‘do more.’”

Cuomo responded on Twitter: “Happy to do your job, too. Just give me control of the Army Corps of Engineers and I’ll take it from there.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.