One of Finance’s Few Black CEOs Thrives Where Big Banks Fled

Trying to Change Financial Habits in the Land of Payday Lenders

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Darrin Williams thinks it was probably a Fox News interview he did in early April that caught the eye of the White House and got him invited later that month to a videoconference with President Trump, his daughter Ivanka, and other top advisers. The pandemic was raging, and Trump had convened a lineup of financial luminaries to discuss how to save the economy. Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin took notes as Brian Moynihan, chief executive officer of Bank of America Corp., and Goldman Sachs Group Inc. CEO David Solomon opened the conversation. Then came Williams, who runs Southern Bancorp Inc. in Little Rock.

Williams is one of only a handful of Black CEOs at financial institutions with more than $1 billion in assets. At $1.6 billion, Southern Bancorp is a minnow next to the trillion-dollar-size whales that more commonly have access to Trump. But in this conversation, just four days after the federal government rolled out the Paycheck Protection Program to provide $350 billion in loans to keep small businesses alive, the little bank in Arkansas emerged as the most relevant.

Business owners at the time were complaining that many banks couldn’t even accept their loan applications, let alone write them a check. Moynihan and Solomon told Trump the best way to get money quickly to the people who needed it most was to use a network of small lenders known as community development financial institutions, or CDFIs, modeled after Southern Bancorp. Williams had worked through the previous weekend to help review loans and send out 50 checks to customers in the Mississippi Delta. “These communities are hurting,” he told Trump, urging the administration to rely more on CDFIs.

It was essentially the same thing Williams had been saying for years as larger banks abandoned places like the Delta. Growing inequality was leaving a huge chunk of the population behind, primarily those from Black and other minority communities. The pandemic finally made the scale of the crisis clear, with families lining up in cars at food banks within weeks of the first shelter-in-place orders. In the second round of PPP loans, the administration set aside $10 billion for CDFIs. “If you use channels that are themselves limited, you’re going to have limited access to people,” says Williams, whose bank ultimately issued $111 million in PPP loans to almost 1,300 customers. “That’s not knocking traditional banks—they’ve left those communities. It’s not their model.”

Largely ignored for years, Southern Bancorp and other CDFIs are experiencing something of a rebirth, attracting hundreds of millions of dollars from technology and finance companies that have been some of the country’s biggest economic winners. The funding includes both direct grants and low-interest loans that allow CDFIs to expand their own lending. Google, for instance, in March said it would provide $125 million in loans and added an additional $45 million in June. Bank of America committed $250 million in March and Goldman Sachs $750 million a month later. Hope Credit Union, based in Jackson, Miss., attracted a $10 million deposit from Netflix Inc., part of a plan the company announced in June to invest 2% of its cash holdings— up to $100 million—with banks that serve Black communities.

All of this was a result of the virus, but also of the outpouring of interest in issues of equality raised by the national protests of police killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and other Black people.

Williams appreciates the attention—but also finds it hard not to ask what took so long.

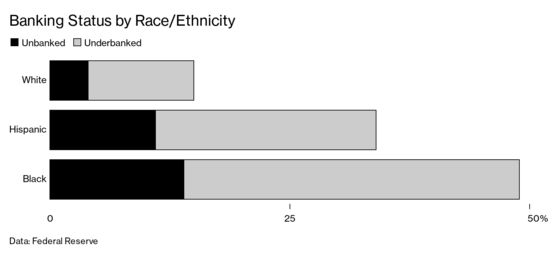

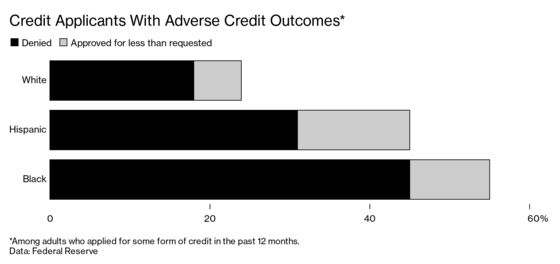

Even before the virus hit, Williams, driving on U.S. Route 278 through mile after mile of Delta cotton fields one day in late 2019, was anything but optimistic. At the time, Black unemployment had reached a record low of 5.4%. But he knew that Black adults were three times as likely as White adults not to have a bank account—the passport to buying a house, the largest source of wealth for most Americans. Some towns in the Delta operate almost entirely on cash, with few businesses accepting credit cards.

The depth of mistrust in the financial system came as a shock to Williams when he joined the bank in 2013, after first resisting the job offer. He was finishing up a term in the Arkansas House of Representatives and had a comfortable job as a partner at a Little Rock law firm, Carney Williams Bates Pulliam & Bowman. He told his wife it felt like a dead end to go into community banking when brick-and-mortar branches seemed to be on their way to obsolescence. She reminded him, “ ‘Darrin, years ago you told me if you could do what you wanted to do, you would help people—this sounds like God just gave you the offer,’ ” as he recalls it.

Southern Bancorp traces its history to an experiment in Arkansas. In 1986, Bill Clinton, then the state’s governor, put together $10 million in local investments to form a development bank targeting rural, impoverished, and minority communities. Hillary Clinton, then a Little Rock lawyer, and Rob Walton, eldest son of Walmart Inc. founder Sam Walton, were on the first board. As president, Bill Clinton used Southern as one of his models for a 1994 law that extended federal support to community lenders. The law created a CDFI Fund to provide equity investments, capital grants, loans, and technical assistance. There are now about 1,100 CDFIs across the U.S., with more than $200 billion in assets; they also have access to bond guarantees and administrative support from the Treasury.

Systemic racism in banking has deep roots going back to the Freedman’s Savings & Trust Co., a private corporation established by Congress in 1865, as the Civil War was ending, to accept deposits from freed slaves and Black soldiers. The bank grew to 37 branches in 17 states before self-dealing and reckless investments by its White trustees caused its collapse in 1874, says Tim Todd, an historian for the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City and author of Let Us Put Our Money Together: The Founding of America’s First Black Banks. Some 61,000 people lost $3 million, equivalent to more than $65 million today. “That was the least of the loss—all the faith in saving went too, and much of the faith in men,” W.E.B. Du Bois later wrote. More recent experience has echoed that betrayal, from redlining and other discriminatory lending practices to predatory subprime mortgages that contributed to the 2008 financial crisis.

When it comes to financial services, people in the Delta often rely on high-interest payday lenders. They’re ubiquitous here—by Williams’s count, Mississippi has more of them than it does Burger King, McDonald’s, and Starbucks outlets combined. There are almost 20 payday lenders within a few miles of Southern’s branch in Clarksdale, Miss. Their appeal is obvious, even if the financial benefit is one-sided. When people walk into a payday lender, employees welcome them warmly. They recall customers’ birthdays and the names of family members.

By contrast, the national banks discourage poorer—and less profitable—clients through minimum-balance requirements and fees. And in many small towns around the Delta, good luck even finding a big traditional lender. From 2012 to 2017, low-income rural communities lost 14% of their bank branches, according to a Federal Reserve study. The number of banks defined as “minority deposit institutions”—either owned by people of color or serving those communities with a board also largely composed of people of color—fell from 215 before the 2008 financial crisis to 149 in 2018. Just 23 of those were Black-owned or served Black communities.

Southern Bancorp takes on payday lenders with what’s known as a credit-building loan, at an annual interest rate of 9%, vs. rates as high as 400% at payday lenders. Half of the money advanced in a credit-building loan is given to the borrower to pay bills, and the rest is kept at the bank as a certificate of deposit. Once the loan is paid off, the certificate becomes a savings buffer. One such loan in 2015 helped a high school teacher in Cleveland, Miss., Jennifer Williams (no relation to Darrin), pay off nine payday loans in three different cities. It was costing her almost $800 a month just to keep current, without doing anything to cut the principal. The payday lenders still call just to check in, especially around the holidays, and they’ve been calling more regularly during the pandemic. “I politely decline them,” she says.

Before the coronavirus, the bank’s primary tool for attracting and educating potential customers was what it called financial boot camps, usually held in churches and community centers. That was the strategy in tiny Sidon, Miss., where Southern Bancorp was the only bank for miles around. But the company closed its lobbies to walk-in customers in mid-March and had to call off the boot camps because of social distancing rules. It employs credit counselors to work with borrowers, and recently they’ve begun experimenting with Zoom calls. But it’s hard to get people’s attention when they’re trying so hard just to survive, especially since the extra $600-a-week federal unemployment benefit ran out at the end of July. “People are saying, ‘I’m not worried about next year. I’m worried about right now,’ ” says Charlestein Harris, one of the counselors.

Around the Delta, the $1,200 stimulus checks ($2,400 for families, plus $500 for each child 16 or younger) from the federal government helped people stay afloat early in the lockdown. It took weeks longer for those without bank accounts to get their checks via the mail. The stimulus was also a boon for payday lenders, check cashers, and others who reaped fees to cash them—usually 3% to 5%, but in some cases as high as 10%. From mid-April to mid‑May, Southern waived fees to customers and noncustomers alike for cashing 4,620 stimulus checks with a total value of more than $7.5 million. Williams says he wishes the stimulus legislation had barred tacking on fees. “Those are things that should have been thought of on the front end,” he says. “It just shows you how often the communities we serve are forgotten.”

The coronavirus is a crisis within a crisis in the Delta. In death and infection rates, the region stands out in the brightest hues on a virus-tracking map of the U.S. from Johns Hopkins University. The Delta is also ranked near the bottom for its expected ability to recover financially and socially after the virus recedes, according to the COVID-19 Community Vulnerability Index from the Surgo Foundation, a nonprofit in Washington. The index looks at preexisting poverty, household income, health, density, and transportation capabilities. A score of 10 is the worst. Many of the counties around Southern Bancorp’s primary areas in Arkansas and Mississippi are 9s and 10s. The bank uses the scores to help guide its lending and makes a point of approaching those in the hardest-hit areas, Williams says.

One loan went to A Healthy You Medical Clinic in Clarksdale, a down-at-the-heels town of 15,000 best known for revitalization efforts centered on a blues club owned by actor Morgan Freeman. Gregory Hoskins, the retired police chief in Clarksdale, opened the clinic in 2017 with his wife, Lula, a licensed nurse practitioner. He runs an auto detailing shop from the same building. As fears of the virus grew in March, patients stopped coming to the clinic. Hoskins called Southern and got a PPP loan to keep wages flowing to the three employees. The loan came through just as he, his wife, and their daughter, who’s the office manager, had their own bout with the virus, forcing them to temporarily shut the clinic; all have recovered. “Had it not been for the PPP, man, I honestly think all the money we had invested in this business—it would have been a problem,” Hoskins says.

Williams has had a bully pulpit since his star turn with Trump and the bank chiefs, and he’s trying to make the most of it. He has a spot on the administration’s Great American Economic Revival Industry Groups task force on banking. It’s met only once since that first videoconference, but the role also gave him a connection to Tim Pataki, director of the White House’s Office of Public Liaison. He’s sent Pataki and members of Congress his policy recommendations, grouped into “now” (this year), “soon” (an additional 6 to 12 months after that), and “long-term.”

Among his ideas for now: Give $5 billion in unused funds from the Paycheck Protection Program to the CDFI Fund. After that, he says, the government should create a federal backstop for bad debt to protect banks if the fragile recovery sputters. And over the long term, the federal government should create a small-dollar loan program to help banks like Southern Bancorp underwrite emergency loans—something that could put the payday lenders and their triple-digit interest rates out of business.

Williams, a Democrat, is careful to avoid being overtly political. “I really appreciate you including the voice of small America,” he said in the call with Trump in April, among several times he profusely thanked the president—whose administration before the pandemic proposed slashing CDFI funding. By Williams’s reckoning, community lenders languished as much under Barack Obama as under Trump: Annual appropriations to the CDFI Fund were $221 million during Obama’s second term in fiscal 2013 and $250 million in fiscal 2019. Williams says he’s hopeful that the attention will mean more federal help no matter who wins the November election.

Still, when it comes to what’s wrong with the communities his bank serves and why, he isn’t mincing any words. Williams wrote a dozen drafts of an internal statement for employees addressing the death of George Floyd. He wanted the statement to be powerful but not shrill. It said the “systemic racism” long suffered by Black families at the hands of police is the “root cause” of disparities in other facets of life, from education to health care to banking. Floyd’s death, in other words, shouldn’t implicate only the police.

“The same disregard for someone that would allow you to put your knee on their neck for 8 minutes and 46 seconds is the same disregard you have for them every day—and whether they have access to services, whether they have access to lenders so they can build a business or they can buy homes where they can grow their family mobility,” Williams says. “The frustration you are seeing is all part and parcel of the same thing.”

Read next: Killer Mike Wants to Save America’s Disappearing Black Banks

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.