Universal Health Care, the South African Way

Universal Health Care, the South African Way

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Ballooning costs that no one seems able to control. A two-tiered system where the wealthy get more attention than they need while the poor don’t get enough. Skyrocketing insurance premiums and malpractice claims. And now a plan to redeploy the resources of the country’s top earners to make health care affordable for the many.

This is South Africa, where the inequities have for years been an exaggerated version of those in the U.S. The African National Congress party, which has led the country for more than 25 years and holds 58% of seats in Parliament, has committed to enacting universal health insurance, outlining the framework in a draft law published in August. Significant questions remain, including which drugs and services will be covered and how the whole thing will be financed. But with the country’s biggest labor group behind it, the bill’s fate is clear: South Africa will soon join the majority of the developed world in providing some form of nationalized health care.

The grand experiment is a more mature version of the health-care debate in the U.S., where candidates for the Democratic presidential nomination are putting their competing visions for what government-sponsored care should look like before voters. Senators Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts and Bernie Sanders of Vermont propose a universal version of the existing Medicare program that would be phased in over several years and replace private insurance. Others, including former Vice President Joe Biden and centrist Pete Buttigieg, advocate a hybrid model that would expand the existing public programs but preserve a private option.

For any of these proposals to become law, there would have to be a dramatic shift to the left, says Bob Blendon, a Harvard health-policy polling researcher. Even when Democrats controlled the House, Senate, and presidency, as they did when the Affordable Care Act was signed into law in 2010, they couldn’t get enough support for a public option. “There would have to be a sea change,” he says.

Politicians and policy experts in South Africa have wrangled for years over what to do about the country’s fractured, two-tiered system. Now, however, “we’re approaching an affordability crisis,” says Andrew Gray, a pharmacy researcher at the University of KwaZulu-Natal who backs the universal health-care proposal, known as the National Health Insurance (NHI) initiative. Not only is the public system starved of funding, private premiums are also precipitously high.

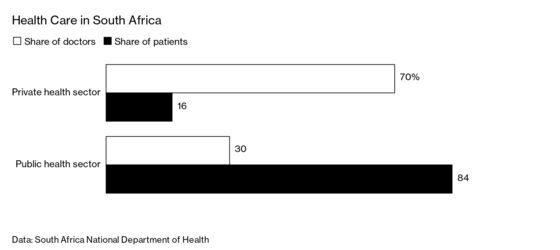

Of the nation’s 60 million people, about 16% have private insurance, many of them white and comparatively wealthy. They’re served by 70% of the nation’s doctors and consume almost half the spending on medical care, according to the health department. That leaves the remaining 84% of the population to crowd into government hospitals and clinics beset by underfunding, broken equipment, and personnel shortages. The most recent government-mandated inspection report showed that just 5 of 696 public hospitals and clinics met at least 80% of the national standards for such measures as drug availability and infection control.

South Africa started talking about nationalizing care after World War II, when the U.K. established its vaunted National Health Service. The leaders of the Commonwealth nation, however, moved in the opposite direction, applying their apartheid regime to health-care facilities as well.

Since the ANC gained power in 1994, the care gap has become increasingly obvious. Years ago, many doctors held jobs in the private and public sectors, evening out resources somewhat, says Solomon Benatar, a health-policy researcher at the University of Cape Town; now that’s less common.

Doctors in South Africa’s private system operate under a fee-for-service model and have wide discretion in how they treat patients, which encourages interventions. For example, three-quarters of pregnant women covered by Discovery Health Inc., the nation’s biggest private insurer, undergo cesarean deliveries, far exceeding the World Health Organization’s recommended rate of 10% to 15%. Only about one-quarter of women in public hospitals get the surgery. Costs in the private system are also driven up by drugs that in some cases cost 7,000% more than they do for public payers.

Experts say savings from wasteful care can be redeployed to widen coverage. If the number of people using the ICU were cut in half and half the savings were used to improve quality in general wards, that would still leave $180 million in annual savings that could be used to bring down the cost of care, says Sharon Fonn, a researcher who helped conduct the Health Market Inquiry, a study of South Africa’s private health sector. Most hospitals dispute the allegation that they overuse their ICUs.

The NHI would take funds going to private insurers and pool them with those in the cash-starved public sector. Based on the draft plan, costs are estimated to top out at about $30 billion annually. While private hospitals will continue to operate, their funding will come from public sources. Private insurers will still subsidize some services, but the majority of coverage will come from the new public system.

ANC lawmakers will have to sell the change to doctors and nurses, particularly those in the private system who may have to live with smaller paychecks. Some private insurers and administrators are worried that when the NHI rolls out in 2026, the role of companies may be reduced to providing coverage for treatment not offered by the state. South Africa’s main opposition party also has said it’s concerned that funds given to the new system will be vulnerable to corruption.

For now, none of those factors appear to be holding back the legislation. Nationalized health care “is going to happen,” says Ronnie van der Merwe, chief executive officer of Mediclinic International, a South African for-profit hospital chain. Some doctors have threatened to leave the system, says Gray of the University of KwaZulu-Natal, but “where are they going to go? Most developed countries already have the same system—except the U.S.”

Backers are battling widely held misconceptions about the plan, including the notion that all private health insurance will be phased out. There will still be a role for private insurers to provide complementary services, and South Africa’s biggest one supports the NHI. It’s a far cry from the U.S., where health-care reform has frequently run aground on industry opposition. “If you told me that 15 years from now a bunch of your customers feel they don’t need private insurance because the public health system is superb,” says Discovery CEO Jonathan Broomberg, “I’d say that’s great.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Rick Schine at eschine@bloomberg.net, Jillian Goodman

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.