South Africa Struggles to Contain Coronavirus While the Economy Crumbles

South Africa Struggles to Contain Coronavirus While the Economy Crumbles

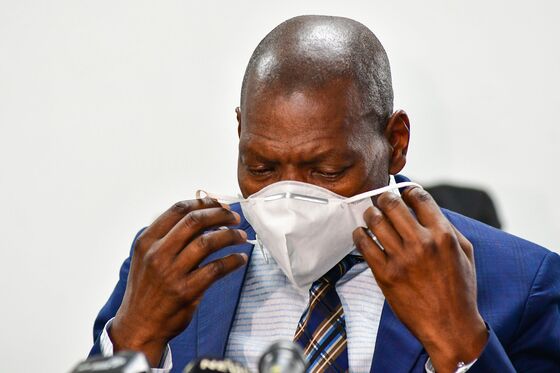

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- While such African countries as Tanzania and Burundi chose to simply ignore the dangers of Covid-19, or lagged on testing and contact tracing—like Nigeria—South Africa did everything by the book. In March, shortly after the first coronavirus case in the country was detected, it shut its borders, instituted one of Africa’s strictest lockdowns, including bans on tobacco and alcohol sales, and rolled out a program to test millions of citizens. President Cyril Ramaphosa won plaudits for mobilizing popular support to help the country weather the disease. His health minister, medical doctor Zweli Mkhize, crisscrossed the nation to carry the president’s message.

Five months later, the country has the world’s fifth-biggest outbreak, with nearly 600,000 confirmed cases. The reason: South Africa’s Covid-19 crisis collided with its ailing economy and dysfunctional politics. The country didn’t have the financial resources to extend many elements of its lockdown any longer than the initial five weeks, as the number of unemployed and hungry surged. By May, it still had fewer than 4,000 cases and only 75 deaths, but the economy had already made a turn for the worse, and the government was forced to allow people to go back to work.

The reopening of the economy was accompanied by a dramatic spike in cases, from 4,000 to 600,000. Still, there is some comfort in that South Africa’s health response has been reasonably effective. With just under 12,000 confirmed Covid-19 deaths, the surge in infections has remained substantially below earlier, pessimistic scenarios that forecast as many as 1.2 million infections and 50,000 deaths this year. In comparison, Brazil has had 3.3 million cases and 108,000 deaths so far.

The country’s multiple crises, however, have exacerbated each other. “We entered the lockdown in a country that was facing a recession and in a country with a fragile health system. On both counts, we were particularly vulnerable,” says Glenda Gray, chief executive officer of the South African Medical Research Council, a body established by the government more than 40 years ago that boasts many award-winning scientists. “It’s a fight between lives and livelihoods. You are never going to find a middle path.”

On the medical front, South Africa must deal with Covid-19, even as the country has the world’s biggest number of people infected with HIV and one of the world’s largest number of tuberculosis sufferers. “South Africa had this very hard lockdown early on, which I think that we all agree flattened the curve and did give us breathing space to get initiatives going, like ventilator projects, beds, etc.,” says Helen Rees, executive director of the Wits Reproductive Health and HIV Institute at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg. “Have we done the right things? I think history will show that yes, we have done the right things in some areas, and we’ve done them well. The health services, although some provinces haven’t been as good as others, have not been overwhelmed.”

The economic response, however, has been less positive. The finance ministry forecasts that the economy will contract 7.2% this year, the most in almost nine decades. The national debt-to-gross domestic product ratio may breach 140% within the decade without urgent action, and as many as 7 million jobs may be lost. The picture is stark and the stakes are high. “We are going into a T-junction,” says Cas Coovadia, chief executive officer of Business Unity South Africa, the country’s biggest business organization. “If we take the wrong turn, we are going into a failed state, if you take the right turn, you are going into a long, hard road to recovery—and it will be hard.”

During the nine-year reign of former President Jacob Zuma, state business became dogged by corruption, and many of the most qualified government employees left its service. That’s put the country in a poor position to implement the programs and reforms needed to bounce back from the impact of the pandemic.

A 40 billion rand ($2.3 billion) program to distribute money to laid-off workers was painfully slow to get up and running as the government’s Unemployment Insurance Fund didn’t have the ability to make the payments efficiently. The 200 billion rand debt-relief program agreed upon with the nation’s banks has been only partially distributed, and a government pledge to cut spending by 230 billion rand over the next two years is under threat from a lawsuit by labor unions that object to the freezing of civil servant wages.

For the first time in its history, South Africa has taken out a loan from the International Monetary Fund. This has raised furious political opposition that has cited the painful experiences of indebted African nations in the 1980s and 1990s. Meanwhile, an alcohol ban that was imposed, then lifted, and then reimposed—as well as frequent changes to school reopening dates—has irked a weary populace. “Whilst the imposed lockdown has had a devastating effect on the economy and livelihoods, the benefit to the public health care is not as clear, given the exponential rise in positive cases, hospital admissions, and mortality numbers in this period,’’ the South African Chamber of Commerce and Industry said last week.

While the country has administered more than 3 million tests, dwarfing the attempts to track Covid-19 made by other African nations, significant delays in getting results have reduced their usefulness. Government permission for the holding of funerals and church services and clearance for minibus taxis (a ubiquitous form of public transport) to operate at full capacity were seen as political decisions.

A Covid-19 scandal also has tarnished the government’s reputation: A slew of people connected to the ruling African National Congress, including Ramaphosa’s spokeswoman and the sons of the party’s secretary-general, have been tied to tenders to supply the state with personal protective equipment, often at inflated prices. “Corruption has reared its head in the procurement of PPE,” says Martin Kingston, vice president of BUSA. “It’s most unfortunate that its happening at the expense of people’s lives.” The spokeswoman—whose husband bid for the tender—said it was an “error in judgment” and has taken a leave of absence from her job. The party secretary hasn’t commented on the allegations, which involve his sons, but the ANC has said business done by relatives of its officials procuring PPE for the government will be probed by its integrity commission.

Ramaphosa, Finance Minister Tito Mboweni, and even the country’s labor unions—often the most implacable foes of change to the status quo—have called for urgent reforms to protect and create jobs and boost growth. In June, the president launched a plan to attract as much as 2.3 trillion rand in private investment in infrastructure over the next decade. Government recovery plan documents are laced with references to the sale of green infrastructure bonds, inclusive growth, and eliminating the bureaucratic logjams that have been holding back the economy.

Business and labor leaders are skeptical that much action will be taken. The lack of skills in many government departments and rampant corruption and infighting within the ANC over the country’s economic direction make implementing the plans a tall order. “My confidence in the government implementing this is very low,” says Busi Mavuso, CEO of Business Leadership South Africa, which represents some of South Africa’s biggest companies. “We understand that we don’t have a capable state. We have a government that is in disarray, that is at war with itself, that is self-mutilating.”

A plan by Business For South Africa, an alliance of the nation’s biggest business organizations that includes BUSA and BLSA, to boost South Africa’s gross domestic product to $550 billion by 2030, from $330 billion now, and to reduce unemployment to 15% has been largely ignored by government.

Meanwhile, planned investments are being canceled, threatening to worsen the economic downturn. Anheuser-Busch InBev and Heineken are among alcoholic beverage producers and glass-makers that have put at least 12.8 billion rand of investment on hold as a result of the alcohol-sale ban. Paper-maker Sappi and real estate company Growthpoint have also put back billions of rand worth of investment, according to Johannesburg’s Business Day newspaper. Many smaller businesses, such as restaurants and gyms, have had to close permanently.

“The economic response has been haphazard, late, and poorly thought-out,” says Peter Attard Montalto, head of capital markets research at Intellidex. “At the heart of it, government never approached the question of what the balance between lives and livelihoods should be, nor the negative consequences of the lockdown or the efficacy of the measures.”

For the most part, there’s recognition that it has been a difficult balance between saving lives and protecting an already weak economy. Even in the health-care system, the diversion of resources from HIV and TB programs to tackle the coronavirus outbreak, and the reluctance of people to visit health facilities for fear of contracting the disease, have led to “collateral” deaths. Some Covid-19-related deaths may not have been recorded. By July 29, South Africa had had more 33,000 excess deaths from natural causes, triple the number attributed to the coronavirus, according to the medical research council.

“Some things are going to be questioned in the future, but the fact is that we have managed to get a lot of initiatives going; we haven’t had overwhelmed health services; we have managed to try and regulate things like personal protective equipment,” says Rees of the Wits institute. “It’s not been perfect. Have there been things that have been wrong? Yes: corruption, people making money off the back of a pandemic. For the rest, history is going to look at all of our responses and we’re going to say, what do we learn from that?”

As even countries who have dramatically reduced infections have discovered, the virus will not rest. “We may have got past the peak of infections, but we’re still going to see a number of deaths over the next few weeks,” says Richard Lessells, an infectious disease specialist at the Kwazulu-Natal Research Innovation and Sequencing Platform, a Durban-based research institute known as Krisp. “It certainly looks like there are fewer hospital admissions and fewer positive tests. That’s definitely encouraging but, like we’ve seen around the world, that still needs to be treated with a lot of caution—because this is not the end, by any means.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.