Social Security Could Stay Solvent Forever by Issuing Bonds

Social Security Could Stay Solvent Forever by Issuing Bonds

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- A monthly check from Social Security is the only thing keeping millions of older Americans out of poverty. Half of married senior citizens and 70% of unmarried seniors get at least half of their income from it, according to the Social Security Administration. It’s the indispensable retirement solution. But the trust fund that pays old age and survivor benefits is going to run out of money sometime in the 2030s.

Those hard facts have raised a question: Should Social Security stop depending just on payroll taxes and the trust fund to pay benefits and start supplementing those sources with general tax revenue? The debate came to a boil in August, when President Trump floated the idea of a permanent cut in payroll taxes, which would presumably necessitate a big infusion of general tax revenue to keep beneficiaries whole.

A lot of advocates for Social Security worry that tapping general revenue will make people perceive the program as welfare rather than a mutual insurance compact among workers. Democratic Representative Richard Neal of Massachusetts, chairman of the Ways and Means Committee, responded to Trump’s gambit with an Aug. 14 statement saying, “Make no mistake: This is an attempt to undermine Social Security entirely.”

On the other hand, drawing on general funds would make it easier to pay scheduled benefits to the Baby Boom generation without big hikes in payroll taxes. It could also lessen inequality, since the IRS’s tax code is more progressive—that is, with higher rates for higher incomes—than the Social Security Administration’s. “The most likely scenario” as the path of least resistance “is somehow general revenues will be tapped” to help pay benefits when the trust funds run dry roughly a dozen years from now, says John Shoven, an emeritus professor of economics at Stanford.

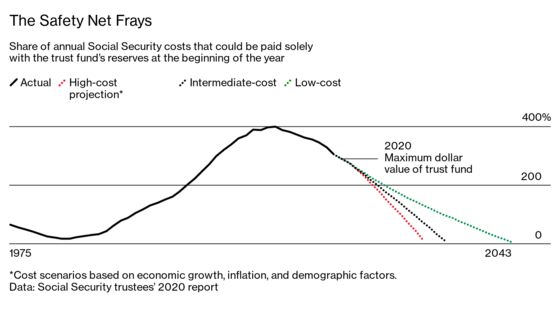

Benefits are paid out of two trust funds, a big one for old age and survivor benefits and a small one for disability insurance. Since a formula change in 1983, the funds have grown because receipts and interest have exceeded expenses. Sometime this year—it’s not clear when—their combined value is peaking at $2.9 trillion. Then it will be all downhill, because benefits have begun to exceed the combination of receipts and interest. The trustees’ report this spring predicted the main fund would run out of money in 2034 and the disability fund in 2065. The Covid-19 pandemic is likely to accelerate the depletion of the main fund by two or three years by reducing payroll tax receipts and pushing people into earlier retirement, Shoven estimates.

Exhaustion of the funds doesn’t cause benefits to go to zero, because fresh money will still arrive in the form of payroll taxes on current workers. But that will cover only 76% of old age and survivor benefits, the Social Security trustees estimated this spring.

Faced with this scenario, the usual response is to choose from an unpalatable menu for fixing Social Security’s finances, such as raising the retirement age, choosing a stingier cost-of-living adjustment, or increasing the payroll tax rate. Democratic Representative John Larson of Connecticut, chairman of the Social Security subcommittee of the House Ways and Means Committee, is sponsoring the Social Security 2100 Act, which raises benefits slightly while gradually lifting the payroll tax rate for workers and employers from 6.2% to 7.4% and subjecting wages over $400,000 a year to payroll taxation.

But none of the choices on the menu undo the core problem, which is that American society has aged. The number of beneficiaries per 100 covered workers has risen from 25 in 1965 to 29 in 2000 to 36 this year, and it’s expected to reach 45 by 2040. And wages—the source of Social Security financing—have shrunk as a share of the economy. Labor’s share of the costs of the private, nonfarm business sector fell to 62% in 2018 from 68% in 2000, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Using general revenue would allow Social Security to tap into sources of money that have grown as a share of the economy, such as business profits. Capital’s share of the costs of private, nonfarm businesses has risen to 38% from 32% over the 18 years since 2000, the BLS calculates. That trend could continue if automation wipes out more jobs while raising income from investments.

Trump’s intentions on the financing of Social Security have been unclear. On Aug. 8 he ordered Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin to defer some payroll taxes for the period from Sept. 1 through Dec. 31 as a way to combat the Covid-19 slump by leaving more money in workers’ pockets. Trump went much further in spoken remarks that day in Bedminster, N.J., while signing the directive, saying, “If I’m victorious on Nov. 3, I plan to forgive these taxes and make permanent cuts to the payroll tax.” On Aug. 12 he told reporters at the White House, “We’ll be terminating the payroll tax after I hopefully get elected.” But aides to Trump said that wasn’t actually the plan. White House Press Secretary Kayleigh McEnany said on Aug. 13 that Trump wanted nothing more than “a permanent forgiveness” of the four months’ worth of payroll taxes. “The president’s very clear on this matter,” she said.

Connecticut’s Larson says there’s an “esprit de corps” among Social Security recipients that would be strained if the system relied on general revenue. But that sense of togetherness, assuming it exists, will get more strained if the system’s finances are fixed on the backs of high earners, either by raising their taxes or cutting their benefits. (Fixing it on the backs of low earners is, for good reason, a political nonstarter.) Making Social Security more progressive by changing the tax and benefit formulas to help lower-income families is probably the right move economically, but it will inevitably make the program seem more like a means-tested transfer program. In which case, why not go ahead and truly make it a means-tested transfer program that draws on all of the nation’s financial wherewithal, not just on payroll taxes?

The justification in the 1980s for bulking up the trust fund for old age and survivors was that the huge Baby Boom generation would prefund its own retirement. It would pay into the fund while working and then draw the money down in retirement. The flaw in the logic was the false assumption that the rest of government would run a more or less balanced budget. That didn’t happen. Instead, the “off-budget” surplus in Social Security offset—or essentially hid—a growing “on-budget” deficit in the rest of government. “Competition between two political parties exploits the ignorance of voters” who don’t understand federal budgeting, Kent Smetters of the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School wrote in a 2004 paper, “Is the Social Security Trust Fund a Store Of Value?”

“Ignorance” is a bit strong, but it’s fair to say Social Security’s role in the federal budget balance is confusing. The trust fund isn’t invested in gold bars or ranchland. Its only holding is special securities issued by the Treasury. In other words, Social Security has lent $2.9 trillion to the Treasury, which spent it all. Now Social Security wants its money back to cover benefits. So starting this year, it’s redeeming some of those special Treasury securities. To raise the money to pay Social Security, the Treasury draws on general revenue. Ten years ago, Social Security Chief Actuary Stephen Goss correctly stated in the Social Security Bulletin that redemption of the trust fund would require the Treasury to “collect additional taxes, lower other federal spending, or borrow additionally from the public.”

What happens when the trust fund runs out will depend on Congress. If it does nothing, old age and survivor benefits will drop overnight by 24%. That’s unlikely. It’s more likely that sometime between now and then a blue-ribbon commission will recommend, and Congress will pass, some package of tax hikes and benefit cuts.

But Congress has another option. It could allow Social Security to issue bonds—in other words, to borrow from the Treasury. Over a period of decades, the borrowing would likely grow into the trillions of dollars. But this would be one arm of the federal government owing money to another, the equivalent of your left pocket owing money to your right. In other words, sustainable.

If Social Security borrowed from the Treasury, the Treasury would have to raise the money to lend to Social Security by raising taxes, cutting other spending, or borrowing. But of course, that’s what the Treasury is already doing as Social Security redeems some of the special Treasury securities in its trust fund. From the Treasury’s viewpoint, there is zero difference between giving cash to Social Security for new bonds it issues and giving cash to Social Security for old Treasury bonds that it redeems.

It’s not Plan A, but a solution along those lines is likely to become part of the conversation over the next decade as the Social Security trust fund plummets toward zero.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.