Small-Business Owners Say PPP Isn’t the Solution They Need

Small-Business Owners Say PPP Isn’t the Solution They Need

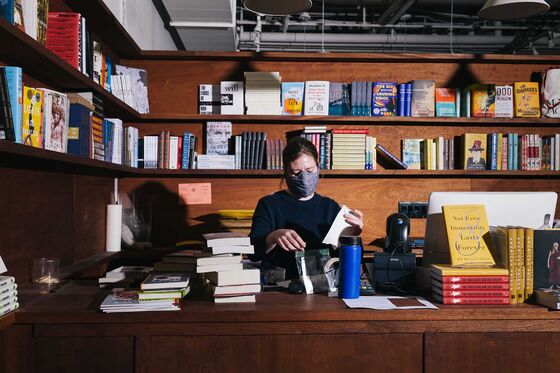

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- If anyone had mastered the art of running bookstores in the Amazon age, it was Sarah McNally. Her flagship McNally Jackson shop in SoHo and a second location in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, were filled on evenings and weekends with customers who appreciated her carefully chosen titles. Recently, she’d doubled the size of her company, opening two additional stores—just in time for the coronavirus pandemic. “It was terrible timing,” she says in early April.

McNally tried to figure out how to keep her shops open. Maybe people could still pick up preordered books? But on March 15, workers who were part of the Retail, Wholesale, and Department Store union representing most of her 115 employees staged a sickout and petitioned her to close the stores for safety reasons. She furloughed all but 20 workers with a week’s pay and shifted her business online. On Twitter, some customers vowed never to patronize the stores again; McNally, however, felt she had little choice if her company was to survive. It didn’t matter to detractors that she promised to pay health insurance through May and, depending on revenue, until the end of June.

Like almost every other small-business owner in the U.S., McNally read less than two weeks later about the passage of the $2.2 trillion Cares Act. It provided $349 billion in loans (at 1% interest) for small businesses through the new Paycheck Protection Program, which the Small Business Administration would oversee. The Department of the Treasury and the SBA promised that PPP loans would be forgiven as long as borrowers spent 75% on payroll within eight weeks of getting the money.

McNally had never had any dealings with the SBA, which has long been overlooked by many of the 30 million small businesses it’s supposed to help in normal times. Their largest advocacy group, the National Federation of Independent Business, surveyed members in 2006 and found that while almost all had heard of the SBA, only 17% were “very familiar” with it. Karen Harned, executive director of the NFIB Small Business Legal Center, says that was still the case until the announcement of the PPP. “Now everybody’s like, ‘Oh, I need to find out about these SBA loans,’ ” she says.

The PPP rolled out on April 3. It didn’t go well. The SBA’s computer system choked on the volume of applications; on Day 1, the administration processed 70,000 loans, more than it handled all of last year, according to an account from Marco Rubio, chairman of the Senate Committee on Small Business and Entrepreneurship. Three days after the launch, the overwhelmed system was inaccessible for hours. Then there were reports of PPP funds flowing to companies that strain definitions of “struggling” or “small,” which the SBA generally puts at fewer than 500 employees. Shake Shack Inc., which had almost $600 million in revenue last year, got $10 million. The Los Angeles Lakers, worth an estimated $4.4 billion, got $4.6 million. Both have said they’re returning the money.

Congress had been reluctant to grant the SBA responsibility for directly handing out PPP money. The agency has a history of being flat-footed; it was criticized for its glacial doling out of loans after Hurricane Katrina in 2005. Instead, the government charged the SBA only with guaranteeing loans that would be made by banks and other private lenders who were likely to get money out the door sooner. Even that would be a challenge for the SBA, given that $349 billion is 12 times the volume of loans it approved last year.

Banks say they were flooded with applications as well as frequently changing guidance from the SBA and Treasury. This was a departure from how lending institutions, which tend to favor existing clients, normally operate. The SBA’s largesse with burger chains—and the difficulty businesses without cozy lender relationships had getting help—ignited a populist backlash.

On April 16, thirteen days after the PPP began, the SBA reached the cap of loans it could guarantee and stopped taking applications. The program was rebooted with an additional $320 billion on April 27, and the SBA started processing applications again despite familiar technical difficulties.

The question for many small-business owners, especially in places such as New York, is whether the cash is a blessing or a curse. Proprietors such as McNally, who run shuttered nonessential businesses with no reopening date in sight, have to adhere to SBA forgiveness conditions that stipulate they can spend only 25% on rent, mortgage interest, and utilities. Do they bring back employees while their stores are closed and risk exhausting the other 75% before they can open their doors again? Do they use the bulk of it to cover immediate expenses and possibly face unspecified penalties? Or do they not ignore free money for people who could desperately use it, accepting that while more help is needed than is being offered, the PPP does have the word “paycheck” right in the name?

The SBA has long struggled for respect. Started in 1953 during the Eisenhower administration, its mission is to nurture the small businesses that today employ 47% of the nation’s private sector. Along with nudging banks to extend more credit through loan guarantees, the agency runs advisory centers on college campuses to help aspiring entrepreneurs and tries to ensure that almost 25% of federal contracts go to mom and pop. There’s also the disaster-response operation.

Former officials defend the agency. “I have had countries including the U.K., Saudi Arabia, and Spain come to me and ask for the blueprint of the SBA, because they want to copy it,” says Karen Mills, who ran it during the Obama administration and is now a senior fellow at Harvard Business School.

Her boss, however, suggested merging the SBA, a freestanding agency, with the U.S. Department of Commerce to help streamline the government. Free-market purists would rather see the administration abolished; they argue its loan programs tip the scales in favor of some businesses rather than leaving matters to the market’s invisible hand. But the SBA carries on, because, even in a divided Washington, both parties want to be seen as small-business boosters. “If you come out against the SBA and question their programs, the response you get is, ‘Well, you don’t support small businesses?’ ” says longtime SBA critic Tad DeHaven, a research analyst at George Mason University’s Mercatus Center.

In December 2016, President-elect Trump nominated Linda McMahon, co-founder of World Wrestling Entertainment Inc., to be his first administrator. As a U.S. Senate candidate in Connecticut in 2012, McMahon supported Obama’s proposal to do away with the SBA as a stand-alone agency; at her confirmation hearing, she said she was against the plan. She went on to win over her new staff with feel-good campaigns such as the SBA Ignite Tour, in which she visited all 68 district offices. “She’s the best we ever had,” says Johnnie Green, president of the American Federation of Government Employees Local 228, which represents 1,000 SBA workers. McMahon was succeeded in January by Jovita Carranza, a former adviser to Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin and an SBA deputy administrator under President George W. Bush. Despite her experience, nothing could have prepared her for Covid-19.

As small businesses started closing, some Democrats wanted the SBA to make direct loans, like it does during hurricanes and forest fires. Senate Republicans who lead the small business committee preferred to move money more briskly, so it created the PPP. To hasten approvals, the program eliminated guardrails. Borrowers wouldn’t need to post collateral or provide personal guarantees; banks would take them at their word about head counts and claims that their operations were suffering because of Covid-19. The committee’s main concern was keeping people on payrolls. “At the end of the day, if there’s a way to keep people connected to employment, that’s what we wanted to do,” says a spokesman for Rubio, the Florida Republican.

As awkward as it was for McNally to reconstitute her company online, sales took off. Employees jazzed up the website, and she staffed each of the four stores with a worker to handle mail orders. That addressed social distancing concerns. When there were post office snafus, McNally tried making local deliveries herself, but that took a lot of time, and customers couldn’t track packages. Her staff got mad at her. “I’m like, Why is everyone always getting mad at me?” she says.

Online sales generated enough cash to pay her remaining employees and her health-care commitments, McNally says. She had nothing left for rent. She’d paid it for March, but now it was April. The two new outposts were in malls where rent was based on a percentage of sales—so no revenue, no payments, which was fortuitous. Her landlord in SoHo, who’d doubled her rent last year to $650,000 annually, didn’t ask her for it. “She was really nice, which surprised me,” McNally says. “She just called and said, ‘I’m checking on you and your family.’ ” The owners of two buildings where McNally runs stationery stores were also willing to be patient. But an attorney for her landlord in Williamsburg, where she pays $240,000 a year, prodded her with emails, threatening legal retribution if she didn’t pay. (The landlord didn’t respond to a request for comment.) The situation was only going to get worse with May approaching. Extra cash might have been handy, future penalties be damned.

McNally discovered quickly how arduous it would be to navigate the SBA loan process. She had a line of credit for her first two stores with Bank of America Corp. and was considering applying for an almost $900,000 PPP loan based on the formula—two months’ average payroll at all of her stores, plus 25% for expenses. But after a week of back-and-forth, she says, it looked like Bank of America would consider loans for only the first two stores and not the other four, which wouldn’t cover her rent obligations. She sought advice from other small-business owners including Adam Friedland, her eye doctor in Brooklyn. “I don’t know how I became friends with my eye doctor, but I did,” McNally says.

Friedland had closed his practice and laid off his five employees. He submitted an online PPP application at JPMorgan Chase & Co. and was told without explanation that he was ineligible, despite his revenue. “I do $1.8 million a year, and I’ve been with them for 25 years,” Friedland says.

He told McNally about a company he found on Long Island through his optometric trade association that specialized in small businesses. It was willing to work with him, he says, even though he decided to hold off because he didn’t want to have to start spending the money. “There’s no reason for me to hire my employees back,” Friedland says. “There’s nothing for them to do.” McNally contacted the company, National Business Capital & Services. A loan adviser looked over her numbers and told her she was likely to qualify for the full amount. “It was unbelievable,” she says.

National Business Capital matches clients such as doctors, lawyers, and pizzeria owners with its roster of 75 lenders. Its president, Joe Camberato, has a YouTube channel on which he posts upbeat tutorials with titles including “Take Your Business to the Next Level,” “Unleashing Your Financial Destiny,” and “Execute Your Business Growth Plan … NOW!”

Before the pandemic, Camberato says, his company, which he co-founded in 2007, was having its best year yet. He was so sure of forecasts for 2020 that he toured an office building in March with enough room to triple his staff of 100. The following Monday, however, he sent everybody home to work remotely and took up a command post in the office above his garage in Setauket, N.Y. For several days, National Business Capital’s lenders vowed to keep the money flowing. Then they had a change of heart, and Camberato laid off 80 of his team members. The PPP enabled him to quickly hire back 40 of them, and he put everybody to work processing applications. “We literally pivoted overnight,” he says.

National Business Capital usually got about 200 calls a day. Now it was fielding three to four times as many. It helped people such as McNally and Friedland pull together payroll records and IRS documents so lending partners could bless requests and get applications into the SBA system. Once the loans—maxing out at $10 million—were approved, lenders would close them. Depending on the size, they’d collect a fee of 1% to 5% from the SBA. National Business Capital got a sliver of that.

Camberato was on Zoom calls with as many as 100 people—employees, lenders, clients—to stay current on the SBA’s evolving rules. The agency initially didn’t provide lenders with much direction, he says. For example, they didn’t learn of the 1% interest rate on loans until the night before the program began. The SBA’s application form, which National Business Capital uploaded to its website, was replaced several days later by another, requiring the company to retrace its steps. (“I had my tech guys working 24 hours a day,” Camberato says.) The SBA posted a promissory note that mentioned collateral requirements. When banks pointed out that the PPP didn’t mandate this, the agency told them to come up with their own forms overnight. At the same time, the SBA’s computer system, the marvelously antiquated-sounding E-Tran, kept crashing, he says.

As Camberato talked to bankers and borrowers and realized that the volume of applications was overwhelming, it became clear to him that PPP funding would soon be gone. He pushed to get as many applications approved as possible. On April 17, McNally got a call from one of Camberato’s employees, who told her that her request had been approved by Fountainhead Commercial Capital in central Florida, which was being inundated with requests just as larger banks were. All she needed now was the SBA’s guarantee, and Fountainhead could release the funds. “He said I was the only happy call he was making all day,” McNally says. “His own mother didn’t get it. He applied for her, too.” (Fountainhead declined to comment for this story.)

That was the day after the PPP ran out of funds. It was too late for National Business Capital’s lenders to pay out their 2,000 approved loans, including McNally’s. Camberato says the lenders were too swamped to get his applications into E-Tran. He says it was devastating for his clients, and his company hadn’t seen a dime for its work. It stopped taking new applications and laid off almost everyone except for a skeleton crew to focus on ensuring that borrowers like McNally got their money when the SBA started the spigot flowing again.

Many people I talked to for this story who aren’t small-business owners had connections to ones who were struggling. Steve Preston, a former SBA administrator under George W. Bush and now chief executive officer of Goodwill Industries International Inc., was seeking PPP money for the nonprofit; he worried that many of its 157 local organizations have more than 500 employees, however, and might not qualify. John Irons, a macroeconomist and fellow at New America, a think tank in Washington, was studying the PPP in part because his father and two brothers are small-business owners and he wanted to help guide them through the approval gantlet. “It’s been hard for me to understand,” Irons says. “And I have a Ph.D. in economics.”

One of my brothers, who works for a tech startup in Philadelphia, was hoping it would get a PPP loan. My brother-in-law, a penile implant salesman who lives on Long Island, had applied for one as an independent contractor. His daughter, who’s training to be a financial adviser at a big bank, was working on weekends to approve PPP applications.

In Washington, even after the first round of funding dried up and headlines appeared about unintended beneficiaries, the Trump administration declared the PPP a success. Mnuchin and Carranza said the SBA had made 1.7 million loans in less than 14 days. When a reporter at a White House briefing asked how many jobs the PPP had saved, Mnuchin said 30 million. Treasury didn’t respond to requests for comment about how it arrived at this figure.

In reality, the PPP hadn’t done much for small-business owners. After the funding initially ran out, the National Federation of Independent Business found that 74% of small-business owners had applied for loans, but only 20% had gotten money from their lenders as of April 17. Most had no idea where they were in the process.

By late April, with the PPP funded again, Fountainhead had submitted McNally’s application. She wasn’t in a rush for it to be approved. The longer she waited, the more likely she’d be able to use the funds when her shops were open, though that could still be a while. It seemed weird to have some people being paid and not working and some people being paid and working, McNally says.

Even if the loan came through, she says, the 25% allotment for nonpayroll costs would cover only one month’s rent at her stores. Her landlord in Williamsburg was now willing to give her a month’s free rent, but that did little to solve her money problems. She was thinking about treating her PPP money as a low-interest loan, using it as she pleased. Still, she was worried because Mnuchin and the SBA had threatened to go after borrowers who use the money for “unauthorized purposes,” without spelling out what that meant.

I’d been trying to get her back on the phone. Let’s talk now, she said in an email. Her plan was to spend the remainder of this beautiful spring day trying to clear her head by—perhaps not surprisingly for a bookstore owner—reading. Of course, it was Boccaccio’s Decameron, a 14th century work about 10 young people who flee the Black Death and take refuge in the countryside outside Florence. But she was currently taking her dog for a walk and available. “It’s infuriating,” she said of the PPP.

Most aggravating to McNally and other small-business owners is that the SBA is forcing them to use PPP money on payroll. What’s in it for them? they ask. Critics, not to mention furloughed workers, argue that’s a callous calculation, especially when the money is potentially free: Suggesting employees collect unemployment benefits—which Congress made more generous in the Cares Act—might not be an enlightened position for people reading Italian Renaissance writers. Rubio has asked the SBA and the Treasury Department to let businesses use a greater portion of loans for nonpayroll needs, as long as they restore full head counts by June 30. Mnuchin has said that’s not the spirit of the law. The SBA didn’t respond to requests for comment.

“I’m just so pissed off about this whole thing,” says Friedland, the eye doctor. He fears it’s too late to submit an application for his practice, though he did fill one out as an independent contractor, because he owns racehorses. “It’s so unfair. It’s such a stupid, non-thought-out, extra-layer-of-bureaucracy program. They could have held everybody in place at 60% of their salaries. That would have been much better.”

Of course, it’s equally frustrating for employees. Rebecca Gans started working as a bookseller at McNally’s newest Manhattan store in August, making $15 an hour. After she was furloughed in March, it took her five weeks to get unemployment benefits. When she started getting checks, she did the math and found she’d gotten a raise to $21 an hour. Would Gans want to give that up to go on McNally’s PPP-funded payroll? “I honestly don’t know,” she says. “It’s a very strange question to even be thinking about. The goal through all this had been to get my job back, and now that I know that I’d have to take a pay cut, it’s hard to believe.” She says she finds the government’s claim that the PPP is pro-worker specious. “I don’t think this is designed to protect me at all,” Gans says. “There’s this huge incentive to get me off unemployment for the sake of getting me off unemployment. I don’t think that’s good for public health.”

On April 29, McNally’s loan came through. She won’t get money for her new Brooklyn store, she said in an email, because it’s “too new, so it doesn’t qualify (which doesn’t seem fair),” adding, “I have all this money to pay staff I don’t need, and no money to pay landlords! But I’ll make it work.” (Camberato, whose company got a PPP loan through his local bank, is in the similar “shitty situation,” he says.)

A day later, McNally was beside herself again when she learned the IRS isn’t allowing PPP recipients to deduct payroll expenses, meaning that even if she brings back her laid-off employees to have her loan forgiven, she’ll take a tax hit later. She says she feels like nobody’s looking out for people like her. “I’ve actually decided that when I’m done getting this company through the coronavirus, I think I want to get involved in small-business advocacy,” she says. “I’m just outraged. I’m just so outraged.” —With Mark Niquette and Mike Sasso

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.