Phantom Companies Got More Than $1 Billion in Coronavirus Aid

Phantom Companies Got More Than $1 Billion in Coronavirus Aid

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- A federal program meant to help small businesses hurt by the coronavirus pandemic may have sent more than $1 billion to places it shouldn’t have gone, according to a Bloomberg Businessweek analysis of Small Business Administration data.

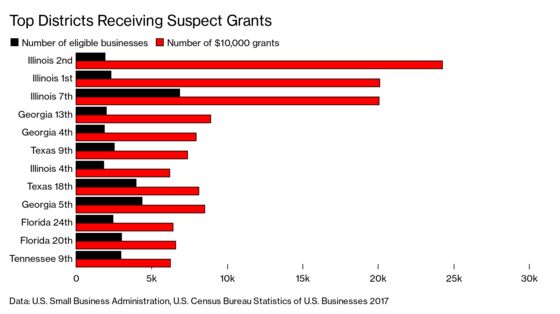

In some parts of the country the SBA approved far more $10,000 Economic Injury Disaster Loan (EIDL) grants than the number of eligible businesses, the analysis found. The epicenter was six adjacent congressional districts in the Chicago area, where 81,000 grants were approved even though there are only 19,000 eligible recipients. That’s more than $600 million going to phantom entrepreneurs.

The SBA declined to comment on the discrepancies, saying in a statement it had “stringent fraud-protection safeguards” and noting that it had been under pressure to move the money quickly.

Bloomberg identified 52 congressional districts across the nation where the number of $10,000 grants exceeded the number of eligible small businesses, for a total of $1.3 billion in suspect payments. Illinois’s 2nd District, which includes a swath of Chicago and its suburbs, had the greatest excess, with 24,278 grants going to businesses that listed addresses there. But the most recent U.S. Census Bureau data show that only 1,925 small businesses in the district have at least 10 employees, the number required to qualify for the maximum $10,000 grant. Districts in Georgia, Texas, Florida, and other states also showed payments to more than the number of eligible companies. The Census data are from 2017, and the number of businesses in each district may have changed since then. But the discrepancies uncovered in Bloomberg’s analysis are so large that potential increases in business activity alone can’t explain them.

The suspect payments far exceed the $47.8 million that SBA Inspector General Hannibal “Mike” Ware identified in a preliminary report in July that warned of “potentially rampant fraud” in the $20 billion grant program. Ware declined to comment on Bloomberg’s findings about the full program until his staff had a chance to review them. But in an interview, he didn’t sound surprised. “The level of fraud we’ve seen in this has been pretty pervasive,” he said.

The SBA said in its statement that its anti-fraud safeguards had “prevented the processing of thousands of invalid applications.” It also said it was “balancing the agency’s fiduciary duties against the urgent need to provide the small-business sector with more than $207 billion—including $20 billion in EIDL Advances—needed to weather the precipitous challenges created by this pandemic.”

The EIDL grant program inspired several types of scams, Ware said. In one, criminals recruit people by offering to help obtain a $10,000 government grant in exchange for a fee. Each recruit provides personal ID and bank account information, often without understanding that the arrangement is illegal. The scammers use the information to submit a phony application.

Ware said he and his law enforcement partners shut websites and call centers that were set up to troll for recruits. “It’s organized,” he said, “to the point where—you know what, I’ll leave it at that, because I don’t believe I can say it publicly at this point.” The FBI, the Secret Service, and other agencies are probing fraud across the SBA’s programs, Ware said.

The Washington Post, citing an unnamed source, reported in July that SBA officials had noticed so much fraud coming from Chicago that they asked front-line workers to subject those applications to extra scrutiny. Separately, the Illinois Credit Union League warned members in a notice on July 3 that it had received reports of “money-mule” fraud in the program. The SBA began dispensing grants in April and handed out the last of the $20 billion in July. Ware’s report says allegations of fraud skyrocketed around mid-June, when the SBA resumed processing applications after a two-month hiatus. The Bloomberg analysis shows a surge in grant approvals on June 15 in areas with the most fraud.

Created as part of the $2 trillion coronavirus stimulus bill passed in March, the grants are an add-on to the agency’s decades-old disaster-loan program, which distributed $184 billion through Aug. 15 to small businesses adversely affected by the coronavirus pandemic. The disaster loan and grant programs are separate from the SBA’s Paycheck Protection Program, which dispensed $525 billion in forgivable loans before it ended on Aug. 8.

It can take months to get approved for a disaster loan, and lawmakers conceived of the grant program as a way to get cash to businesses quickly while applications were pending. Barring fraud, the grants don’t have to be repaid, even if the loan application is rejected. To speed money to struggling businesses, lawmakers required the SBA to take applicants’ word that they were eligible for the money—a requirement that SBA Administrator Jovita Carranza has called “lowered guardrails” against fraud.

In a letter responding to Ware’s findings, Carranza said the SBA had caught billions of dollars of attempted fraud. An automated system rejected $8.8 billion in grants because they were identified as duplicates, and it denied an additional $9 billion because applicants’ identities didn’t check out or didn’t match bank information, Carranza wrote.

Those figures refer to rejected applications. But Ware was able to identify the $47.8 million in fraudulent grants approved through June 19 by examining the employer tax ID numbers on applications. Businesses are supposed to have been in operation as of Jan. 31 to qualify, yet Ware found that 20,962 successful recipients got ID numbers after that date. He used the same method to identify $208 million of loans that were wrongly disbursed.

In some cases, according to Ware, banks alerted the SBA to suspected fraud, and it’s unclear whether all of the dubious approved grants identified by Bloomberg were actually collected by applicants. But the number of suspect approvals may be even higher than Bloomberg estimates. It doesn’t include potential fraud involving grants of $1,000 to $9,000, which represent more than half the total. And it counts only $10,000 grants that exceed the number of eligible businesses in a congressional district, even though some legitimate businesses probably didn’t apply. Across the nation, about 57% of eligible small businesses got $10,000 grants.

Have a tip about how virus relief funds are used or misused? Write us at ppptips@bloomberg.net, or follow instructions to submit an anonymous tip at https://www.bloomberg.com/tips/

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.