How China's Appliance Giant Helped Wipe Out GE's Middle Managers

Six Sigma Gives Way to Rendanheyi at GE’s Appliance Business

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Weeks after sealing a $5.4 billion deal to buy General Electric Appliances (GEA) in 2016, Zhang Ruimin, chairman of China’s Haier Group, stood before 500 anxious GE white-collar workers who asked a barrage of questions about their futures. The irony wasn’t lost on Zhang, revered in China as a pioneering corporate titan but mostly anonymous to the outside world. When Zhang was struggling in the 1990s to transform Haier from a collective village enterprise into a world-class manufacturer, he idolized General Electric Co. because of its reputation for corporate excellence. “We went for courses at Crotonville, studying Six Sigma,” he says, referring to GE’s management training center in New York and the data-driven process-improvement strategy espoused by former Chief Executive Officer Jack Welch. “Now they were looking at me, asking: ‘What can you do for us?’ ”

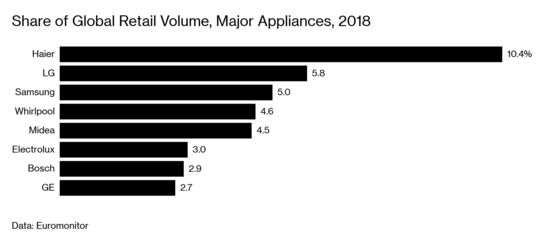

As it turned out, quite a lot. Zhang may have cut his teeth on Six Sigma, but as Haier became the biggest appliance maker in the world, he thought it needed a different playbook to eliminate the sluggish bureaucracy that comes with size. So he created a management philosophy he calls rendanheyi, which translates loosely to “employees and customers become one.”

The ideology seeks to make big companies operate like a collection of startups, emphasizing flexibility and risk-taking—and no middle managers. Zhang thought the approach would help revitalize a stagnant GEA, where sales growth was 1 percent in 2014 and only 4 percent the next year as once-mighty parent GE floundered.

The company says it’s working so far. GEA’s revenue in U.S. dollars grew 11 percent in the first half of last year with the help of new products such as front-control ranges with Wi-Fi connectivity and its Café brand, which features customizable knobs and handles. “We finally feel we have a parent who supports us and wants us to win,” says Kevin Nolan, CEO of Louisville-based GEA. “We view ourselves as part of the biggest appliance company in the world, and we are very proud of that.”

Haier declined to give additional financial details. But annual revenue from its two public entities—Shanghai-listed Qingdao Haier Co. and Hong Kong-listed Haier Electronics Group Co.—is about $40 billion, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

For Zhang, Haier’s remaking of GEA reverses the typical narrative that cash-rich Chinese companies fail when trying to assimilate Western acquisitions. That script was written by the implosion of such deals as TCL’s acquisition of France’s Thomson Electronics, SAIC Motors’ takeover of South Korea’s SsangYong Motor, and Ping Ang Insurance (Group)’s investment in Fortis, which was mostly written off after the Dutch-Belgian financial-services company collapsed during the financial crisis. “Seventy percent of acquisitions fail, and 70 percent of that is because of culture,” Zhang says. “What we are is an example to follow.”

The successful union comes amid increasing diplomatic and trade tensions between the U.S. and China. Zhang says he’s troubled by the disputes, but he’s not worried they’ll affect Haier’s work with GEA. Haier helped bring the company “back to life” and wants to contribute to the U.S., not harm it, he says: “Our GE Appliances employees are feeling fortunate that Haier acquired this company. If not, they might have been laid off.”

Zhang implemented rendanheyi in 2010 at Haier. It advocates dividing monolithic business units into microenterprises that essentially act as startups with quarterly targets. Base salaries are low, with performance-based bonuses added on.

The key tenet of the structure is that every microenterprise has “zero distance” to the customer, he says. Haier organizes business units around individual products instead of traditional functions such as supply chain, factory operations, and distribution. For example, everyone involved, start-to-finish, in the making of a washing machine—from sourcing materials to manufacturing to sales—works in the same microenterprise. “Thirty years ago the company was a struggling collective enterprise turning out products of dubious quality,” Gary Hamel and Michele Zanini wrote in the November-December 2018 issue of Harvard Business Review. “Today it’s a case study in what can be accomplished when an established company is willing to challenge bureaucracy’s authoritarian structures and rule-choked practices.”

GEA’s old management structure created risk-averse silos that crippled the company’s ability to launch products such as water heaters and packaged air conditioners, Nolan says. If a product wasn’t in one of the core businesses—cooking, laundry, refrigeration, and dishwashing—then it didn’t receive the company’s full attention or resources. “Before, every business unit was focused on optimizing themselves,” he says. “Now, everyone is focused on the outside marketplace and focused on how to get their products to win”—which can also mean taking risks on new types of products, he says. “It’s a huge culture difference.”

At Haier Group, where the phrase “middle manager” is almost an expletive, 10,000 people were dismissed after rendanheyi was implemented, even as the company created jobs in growing businesses such as internet-connected appliances, logistics, and delivery. But GEA’s job cuts have been modest, with only two middle managers let go so far. Others were redeployed and more workers were hired as sales increased, the company says. “Haier is well aware of other failed Chinese forays into the U.S. and is trying to avoid them,” says William Fischer, a professor of innovation management at Swiss business school IMD and co-author of a 2013 book about Haier. “Rendanheyi is aimed at proving that big, venerable, old organizations can also be revitalized.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Ellis at jellis27@bloomberg.net, Michael Tighe

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.

With assistance from Bloomberg