On Diversity, Silicon Valley Failed to Think Different

On Diversity, Silicon Valley Failed to Think Different

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Quora Inc., which runs the eponymous questions and answers website, couldn’t figure this one out: Why were so many Black and Latinx college students rejecting its job offers or withdrawing from interviews? Last year, a recruiter suggested that the Silicon Valley company might seem more welcoming if it had dedicated groups of underrepresented employees for the candidates to consult. Higher-ups were initially skeptical, she says, whether the company even had enough diverse employees to do so. Quora says it’s in the process of creating such groups.

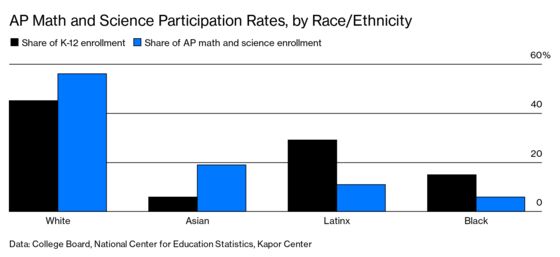

Silicon Valley’s predominantly White, male workforce didn’t have to be this way. The wave of national unrest around ingrained racism has called attention to the dearth of people of color across corporate America. Yet if there’s one industry that should have been able to avoid these problems, it’s technology. Many of today’s biggest tech companies, which frequently use their corporate mission statements to espouse utopian harmony, didn’t exist a few decades ago. They didn’t inherit the same racial disparities entrenched at banks and other centuries-old institutions. Yet they’ve replicated the same rot.

“Tech had started to take over our world, but as the industry added tens of thousands of jobs, it was ushering in the same systemic racism we’ve faced for 100 years,” says Joseph Bryant, who leads PushTech2020, an initiative of the Reverend Jesse Jackson. “It’s not just, ‘Don’t put your knee on my neck.’ It’s also, ‘Help me get a job and build wealth, because I’m qualified and you’re not even looking in my direction.’ ”

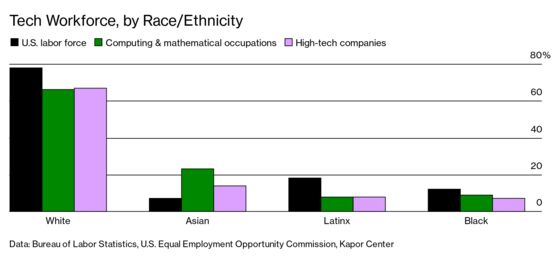

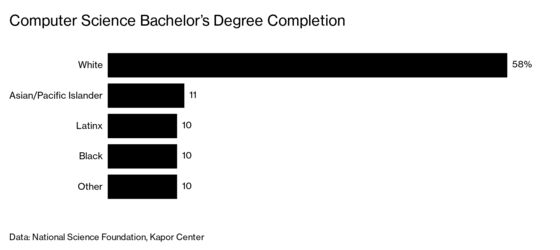

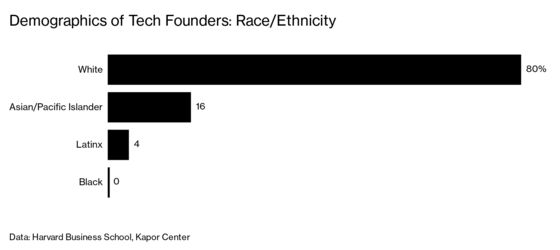

According to the Kapor Center for Social Impact, about 21% of computer science graduates are Black or Latinx, yet they represent only 10% of technical roles at the 20 top-grossing tech companies. More than 97% of tech startup founders and their venture capital backers are White or Asian.

Renewed vows in June by tech companies to diversify their workforces recall years of failure at Microsoft, Facebook, and Google. At those companies, Black employees make up 3.3%, 1.7%, and 2.4% of technical roles, respectively. Proxy statements show there was only one Black executive among the leadership teams at Microsoft, Facebook, Google, Apple, and Amazon.com last year. He was at Google, and he left in January.

To truly make good on all these years of promises, tech companies must start by puncturing two pervasive Silicon Valley myths: that they’re meritocracies where everyone gets a fair shot, and that diversity is a pipeline problem. The reality is that Black employees are leaving faster than they’re being hired because, for people of color, many tech companies can be painful places to work. Getting through the door is one thing; staying and progressing up the ranks to a position of influence is another.

Often, Black employees are the only minorities on their teams. They receive salary offers that average $10,000 less than offers to White peers, according to recruitment marketplace Hired Inc., and take longer to get promoted. Many also incur what’s referred to as a “Black tax”—additional work such as representing the company at career fairs or conducting new-hire interviews, implicitly distorting how diverse the company is. That takes them away from their day job for no extra pay. Small wonder, then, that many tech companies lose more Black employees through attrition in a given year than they manage to hire. To have any meaningful change, tech companies will have to spend as much time—or more—retaining and promoting Black employees as getting them in the door.

And if they want smart people to speak up, they can’t penalize outspoken Black workers. “One of my managers used to call all the things I was doing around diversity ‘extracurriculars,’ ” says Bari Williams, a former Facebook Inc. lawyer who now heads legal at Human Interest Inc., a fintech company. “Leadership can talk about diversity all day long, but if the managers and people who implement it don’t buy in, it’s not going to happen.”

Google came under fire in June after claims that its campus security policy, which encourages staffers to look at the ID badges of passersby to make sure they match the people’s faces, led to discrimination against Black and Latinx workers. Employees who said Black and Latinx workers were subject to disproportionately frequent checks complained to CEO Sundar Pichai, who committed to ending the practice. “It seems small, but over time it makes you feel like you don’t belong,” says one Black employee in the Bay Area, who spoke on condition of anonymity for fear of retribution. It’s a signal that “this space wasn’t built and isn’t intended for us.”

Black Googlers who speak out are criticized even as the company holds them up as examples of its commitment to diversity, according to Timnit Gebru, a Google researcher who uncovered how some facial-recognition programs mischaracterize darker-skinned women. She says co-workers and managers have tried to police her tone, make excuses for harassing or racist behavior, or ignore her concerns. When Google was considering having Gebru manage another employee, she says, her outspokenness on diversity issues was held against her, and concerns were raised about whether she could manage others if she was so unhappy. “People don’t know the extent of the issues that exist because you can’t talk about them, and the moment you do, you’re the problem,” she says.

Google says it began paying closer attention to attrition rates in 2018, when it saw Black and Latinx workers leaving the company at faster-than-average rates. The company says its response efforts included hiring case managers to focus on trying to retain the employees. “Only a holistic approach to diversity will produce meaningful, sustainable change,” the company said in a statement.

The focus on diverse hiring has overshadowed failures to retain new Black and Latinx employees, pay them equally, and promote them. Tech companies’ leaky bucket syndrome makes it look as if their overall workforce diversification efforts are stagnant. That discourages other diverse hires from seeking similar jobs and creates a difficult cycle to break, according to Charlene Delapena, a former recruiter at Quora who now works for another startup and also runs URx Inc., a talent development organization.

Quora says no Black students rejected job offers during last fall’s recruiting season. “It is important to our mission and also to me personally that we provide an environment where people from all kinds of backgrounds can do their best work,” CEO Adam D’Angelo said in a statement.

The push to diversify tech’s ranks can be traced to the 2013 disclosure by former Pinterest Inc. engineer Tracy Chou that women made up just 12% of the company’s engineering staff. Her declaration prompted women at other companies to speak out. “There’s no way we’d get systemic change if we weren’t even willing to release the basic numbers,” says Chou, who now runs Block Party, the maker of an anti-harassment app.

The next year, Reverend Jackson established PushTech2020 in San Francisco. He showed up at the annual shareholder meetings of Google, Microsoft, and Amazon and demanded they disclose their race and gender data. In 2015 members of the Congressional Black Caucus weighed in, meeting with Facebook Chief Operating Officer Sheryl Sandberg and Apple Inc. CEO Tim Cook.

PushTech2020 aimed for 20% of people of color in Silicon Valley by 2020. “We won’t say they totally failed because this story hasn’t reached its endpoint,” says Bryant. “But they haven’t come close.” Top tech companies did begin to disclose their diversity stats and hire chief diversity officers, but five years on, not one such company has anything close to a 13% Black workforce, which would match the Black proportion of the U.S. population. Some companies have even tried to fudge figures by including temporary contractors and cafeteria workers, Bryant says, declining to name names.

Gwen Houston, Microsoft Corp.’s former head of diversity, says Black employees there would quickly become disillusioned by the “only-ness factor” that comes when few minorities are on a team. Promotion and hiring discussions regularly excluded Black employees under the banner of amorphous criteria, such as whether a candidate was considered a good “fit,” she says. When the employees leave, she says, Microsoft’s reputation among other Black job candidates naturally suffers. By the time Houston left Microsoft in late 2017, there had been some progress on increasing the number of women in leadership, but not much on the number of Black people. Twice-yearly talent reviews while she was at the company failed to elevate many Black executives because there were too few of them at a high enough level, she says.

A company the size of Microsoft would need to hire 9,000 Black workers in the U.S. alone to achieve population parity, so losing Black staff stung. “I always used to say we need to be just as invested on the retention as we are on the recruiting because we have to manage this hemorrhaging effect,” Houston says. “Microsoft wasn’t keen on talking about turnover costs.”

Pledges to double the number of Black employees in senior and leadership positions by 2025 will “hold us accountable for progress,” a Microsoft spokesperson said in a statement. “We need to ensure that our culture of inclusion is a top priority for everyone. We acknowledge that there is much more that we need to do to improve the lived experience of Black and African American employees at Microsoft and members of the community in society.”

The opportunity to build a diverse workforce perhaps seemed more promising at a younger company such as Facebook Inc., which has added 42,000 employees globally over the past eight years. Facebook was founded in 2004, Microsoft in 1975. But according to company filings with the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, there were only 260 Black employees in Facebook’s 11,200-strong U.S. workforce in 2016. That count increased to more than 1,000 in 2018, but only after Facebook’s total workforce roughly tripled.

Facebook has managed to increase the proportion of women among its technical employees to 24% in 2020, from 15% in 2014, the first year it published its diversity stats. In that time, however, it hasn’t managed to increase the share of Black U.S. employees in those roles by a single percentage point.

Chief Diversity Officer Maxine Williams, who joined Facebook in 2013, says that failure doesn’t have a simple answer—improving retention will require systemic changes beyond what the company has managed so far, rather than “leaving it up to chance whether someone has a good manager.” Each team will need its own goals, she says. “It’s bloody hard to keep doing this hard work every day.”

In July, Facebook was accused of systemic discrimination by a Black employee in a complaint to federal civil rights authorities. Oscar Veneszee Jr., a decorated former U.S. Navy veteran, said he was denied promotions and stalled by middling evaluations, despite being good at his job. He had three managers in three years and was often the lone Black employee on his team. Veneszee said he was forced to apologize to a White Facebook recruiter after questioning why a list of potential schools where Facebook was actively recruiting only had one historically Black college or university on it. “If someone is being silenced over raising diversity concerns in recruiting, it means next time, someone like Oscar feels like they can’t speak up,” says Peter Romer-Friedman, a principal at Gupta Wessler PLLC who is representing Veneszee. Facebook has said it’s investigating the allegations; Williams declined to comment further.

Facebook in 2013 found zero correlation between alma mater and performance, according to Adam Ward, a former recruiter for the company who now runs his own firm. Current and former Facebook staffers say that despite adding more schools to the recruiting lists, White managers continue to select from the same Ivy League and West Coast schools they’d attended. Many of these institutions act as another racial filter because Black students are often underrepresented. “Companies will give unfair weight to a school like Stanford, dipping down to the top 20% of students, but might pass on a student in the top 2% of their class at Penn State because of baked-in bias,” says Ward. Top roles are narrowly filled with people from other tech companies rather than Black or Latinx executives in more diverse sectors, he says.

Experts say the coronavirus pandemic and global economic slowdown are hurting diversity efforts, too. Businesses are looking for ways to cut costs, and diversity and inclusion teams can be low-hanging fruit. Companies give chief diversity officers “little to no budget,” says Aubrey Blanche, the former diversity head at Atlassian Corp. “They’re trying to solve 400 years of structural oppression and, ‘Oh, by the way, they need to hit their target at the end of the quarter.’ ” —With Alistair Barr

Read next: Social Media, Civil-Rights Groups Brace for Voter Disinformation

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.