Section 230 Was Supposed to Make the Internet a Better Place. It Failed

Section 230 Was Supposed to Make the Internet a Better Place. It Failed

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- One afternoon in July, Ted Cruz banged a gavel on the dais, calling to order a hearing of the U.S. Senate Judiciary Subcommittee on the Constitution. The day’s first witness was Karan Bhatia, a top policy adviser for Google. He gazed up at the panel of senators, alarm creeping into his expression, like a 10-point buck hearing the sudden crack of gunfire.

When elected officials start appending the prefix “big” to the name of an industry, it’s never a good omen. Big Tobacco. Big Oil. Big Pharma. Big Soda. “Sometimes tech companies talk about their products and the effects of those products as though they are forces outside of Big Tech’s control,” Cruz said. “As we’ve heard time and time again, Big Tech’s favorite defense is, ‘It wasn’t me. The algorithm did it.’ ”

For the next couple hours, the senators took turns walloping the most despised industry of the moment. They knocked its carelessness with consumer data, its violations of individual privacy, its tolerance of harassment and misinformation, its censorship of political dissent, and its hospitality toward extremists. “It seems like the problems around Big Tech, as it has become a mature industry, are just mushrooming,” said Senator Marsha Blackburn, a Tennessee Republican. Perhaps it was time, Cruz rejoined, for Congress to revisit Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act—a slim and powerful law, cherished in Silicon Valley, that shields internet companies from liability for most of the material their users post.

Back in 1995, when the CDA was conceived, Section 230 enjoyed bipartisan support from members of Congress, who believed that tech companies would do a better job at moderating the internet than federal regulators. But a growing number of hostile lawmakers are now criticizing Big Tech’s safe harbor. Cruz, a Texas Republican, and other conservatives have accused major internet platforms of suppressing their viewpoints, arguing that the spirit of Section 230 is predicated on the companies remaining politically neutral. Democrats call that nonsense; still, liberals have found reasons to dislike the law, namely their belief that tech businesses have too often used it to ignore the collateral damage of their users’ bad behavior.

Senator Richard Blumenthal, a Connecticut Democrat, said during the hearing that patience with the industry’s careless approach to user safety had run out. “You can’t simply unleash the monster and say it’s too big to control,” he said. “You have a moral responsibility even if you have that legal protection.”

Silicon Valley is unlikely to give up its shield without a fight. Supporters credit Section 230 with helping transform the primordial net into a trillion-dollar industry and securing today’s vibrant culture of free expression. The most important piece of the law is just 26 words long, and yet it’s profoundly shaped American life. It’s no hyperbole to call Section 230 the foundation on which the modern internet was built, from social media to search engines to open source reference guides to the sharing economy. Getting rid of it, Big Tech warns, could jeopardize many of the things on the web we take for granted, from reading and writing product reviews to watching amateur how-to videos on YouTube.

Take it away, and the whole thing could come crumbling down.

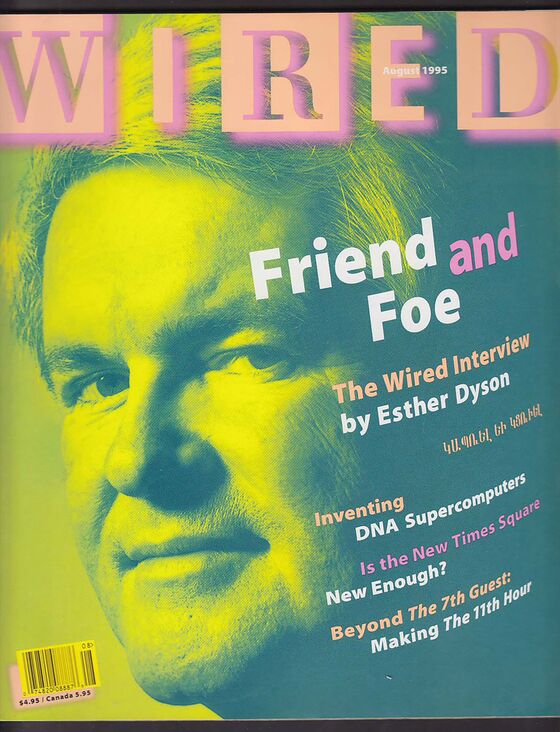

The internet’s right to self-governance wasn’t always universally recognized in Washington. It had to be wrested from lawmakers. In early 1995, Todd Lappin, a top editor at Wired magazine, set out on a mission to liberate the newly born net from the scaremongers in Congress. At the time, the Senate had just started considering the CDA, sponsored by Senator James Exon, a socially conservative Democrat from Nebraska. Under the bill’s provisions, knowingly making indecent material available to minors could lead to hefty fines and even prison time for a net operator. The editors at Wired believed Exon’s law would result in widespread censorship, stunting the web in its early days.

Only two years old then, Wired was already an essential publication for anyone hoping to make sense of the incipient dot-com boom. Its thick monthly issues were jammed with profiles of digital visionaries, reviews of new-wave gadgets, and ads for computers, CD-ROMs, blank 3.5-inch disks, and bottles of cologne and tequila. Lappin got to work, commissioning influential writers to hammer technophobes on Capitol Hill, organizing protests, and working closely with the “netroots,” a decentralized community of activists united by their love of the unfettered web. Few lawmakers were using email yet, so the netizens targeted lawmakers’ offices with “fax bombs,” jamming their machines with mass outpourings of umbrage. They argued in the press that democracy, free speech, and education would suffer with the CDA. “Welcome to digital Singapore,” a critic told the Washington Post.

On June 9, 1995, Exon took to the Senate floor to rally support for the bill, crafted as an amendment to a massive telecommunications reform bill then wending its way through Congress. He brandished a blue three-ring binder containing printouts of explicit photos downloaded from the net, where, he said, any kid with a dial-up connection could find them. He opened the binder and began reading: “Erotica fetish. Nude celebrities. Erotica bondage. … Here’s a good one—erotica cartoons.” Exon shook his head.

The Senate passed his amendment by a vote of 86 to 14, and the netroots shifted their attention to the House of Representatives, which was working on its own version of the telecommunications bill. When Speaker Newt Gingrich went on TV and described Exon’s amendment as a clear “violation of free speech,” cyberactivists rejoiced. In August, Wired put Gingrich on its cover.

At the time, web lobbyists were still a rare breed in Washington, and the CDA wasn’t their only headache. The previous year, an anonymous user on a Prodigy bulletin board had accused a freewheeling investment firm called Stratton Oakmont (which was later the inspiration for The Wolf of Wall Street) of committing fraud. In response, the rowdy Long Island-based business filed a libel suit against the online service provider seeking $200 million in damages. In May 1995, Justice Stuart Ain of New York’s Supreme Court found that, because Prodigy was using screening software to filter out offensive language and moderators to enforce guidelines, it was acting not as a passive carrier but rather in a manner akin to a publisher. It could therefore be held liable for the defamatory language of its users.

A spasm of anxiety coursed through the web. Tech lobbyists huddled with their allies in the nonprofit advocacy world, who for months had been working with allies on the Hill to come up with a less draconian regulatory framework to challenge Exon’s proposal. An idea took hold.

On June 30, two members of the House—Ron Wyden, an Oregon Democrat, and Christopher Cox, a California Republican—introduced the Internet Freedom and Family Empowerment Act. At the heart of it was a stipulation that “no provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider.” The bill also contained a provision declaring that internet service providers couldn’t be held liable for “any action voluntarily taken in good faith” to remove materials from their platforms.

Cox and Wyden told the media that their “good Samaritan” amendment would give internet companies enough legal breathing room to regulate their own communities without fear of getting sued if something heinous inadvertently slipped through. It would be a much more cost-effective way of patrolling the net than the ham-fisted measures passed by the Senate, they said. “Clearly, to guard the portals of cyberspace, the private sector is in a far better position than the federal government,” Wyden told the Washington Post. On Aug. 4, the House passed the amendment by a vote of 420 to 4.

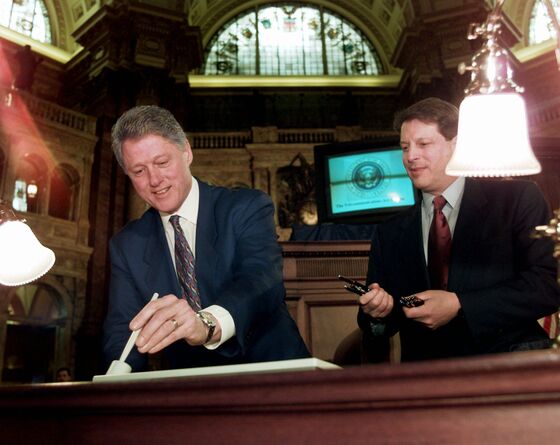

When, months later, members of the House and the Senate met to reconcile the differences between their bills, they jammed Exon’s penalties and Cox and Wyden’s immunity provisions into the final text, leaving it to the courts to sort out the contradictions. On Feb. 8, 1996, President Bill Clinton signed the whole package into law.

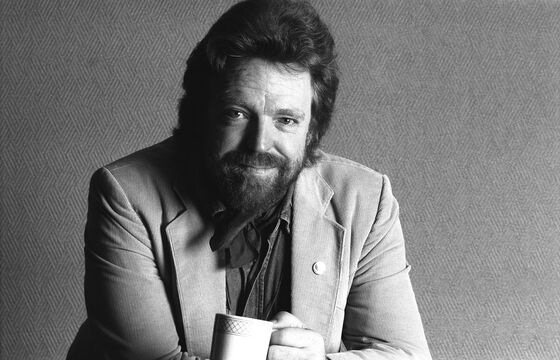

Despite Section 230, the net erupted in protest. For the next 48 hours, more than 1,500 websites, including Yahoo! and Netscape, switched to a black background screen as a warning that the CDA would censor free speech. John Perry Barlow—a netroots hero, who’d previously written lyrics for the Grateful Dead and co-founded the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF)—wrote a defiant email, widely circulated by activists and later republished in Wired, lambasting the law. “Governments of the Industrial World, you weary giants of flesh and steel, I come from Cyberspace, the new home of Mind,” Barlow wrote. “On behalf of the future, I ask you of the past to leave us alone.” He grandly titled his hot take “A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace.”

Opponents filed lawsuits. On June 26, 1997, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down the indecency provisions of the CDA—while all but ignoring Section 230. “In some ways, Section 230 was a kind of sheep in wolf’s clothing,” says Mike Godwin, a lawyer who helped lead the fight for the EFF. “It was basically something that was really good for the internet that was couched as something that would create more policing.”

It wasn’t long, however, before the internet’s preferred version of self-enforcement would get lots of unwanted attention. In the immediate aftermath of the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing, Kenneth Zeran, a Seattle real estate agent, started receiving threatening phone calls. He quickly learned that an anonymous user on AOL was posting his name and phone number alongside ads for fake souvenirs making fun of the tragedy.

Zeran tried frantically to get the company, America Online Inc., to remove his name and number, but it was slow to respond. He later sued, accusing the company of negligence. Lawyers for AOL responded by filing a motion to dismiss, invoking Section 230’s safe harbor. In March 1997, in a federal court in Virginia, Judge T.S. Ellis III ruled in AOL’s favor. Several months later, a panel of judges on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit upheld that ruling, advancing a strikingly broad interpretation of Section 230. They found that if an internet company was notified that its site was distributing something illegal from a third party—be it defamation or death threats—it would remain immune from civil or criminal liability, even if it continued to knowingly propagate the illicit material.

Critics of the law cite this ruling as ushering in a golden age of online harassment. In the years that followed, individuals who felt stung by the negligence of various web communities repeatedly filed suit for damages. Again and again, their cases were tossed out. “By the end of the summer of 2003, Section 230 appeared to be kryptonite to any plaintiffs who were considering a lawsuit against a website or internet service provider,” writes Jeff Kosseff, author of The Twenty-Six Words That Created the Internet. A law that had originally been envisioned as a way to keep the internet clean—or clean enough—instead made it safe for hatemongers, tormentors, and purveyors of misinformation.

Mary Anne Franks, a professor at the University of Miami School of Law, compares the behavior of internet companies under Section 230 to that of gunmakers under the Protection of Lawful Commerce in Arms Act, a 2005 law that provides extensive liability protection to firearm manufacturers and dealers. The freedom to self-regulate, she argues, allows internet companies to ignore public demands to make their products safer—and “we can now see what the industry has chosen to do with that freedom,” she says. “They have not only let a lot of bad stuff happen on their platforms, but they’ve actually decided to profit off of people’s bad behavior.”

In recent months, Wyden, the co-author of Section 230, has said that conservatives are misinterpreting the law’s intent. Rather than encouraging neutrality, the bill was designed to empower tech companies to proactively remove questionable material from their platforms.

“There were two parts to the law,” Wyden says. “There was a shield, and there was a sword. The sword was the legal authority of the website owner to moderate content. It’s clear to me looking at the evolution of time that too many sites—particularly the big companies as they got so prosperous—enjoyed the shield, but weren’t willing to use the sword. I have told them that if they don’t clean up their act and use that authority to moderate content with the sword, people are going to constantly come after them and say, ‘We’re going to take your shield.’ ”

When Section 230 was passed, the leading internet companies were underdogs. Now they’re the overlords of the U.S. economy. The inversion of power means Section 230 cases frequently result in the spectacle of a tech giant squashing the complaints of the wee internet villagers. Section 230 has enabled Twitter Inc. to dismiss allegations that it spread Islamic State propaganda; it’s helped Yelp Inc. avoid having to take down defamatory reviews; and it’s allowed Google to swat away the outcry of neighborhood locksmiths who say that Google search results are overrun with fraudulent listings.

Somewhere along the way, Section 230 crossed over from the realm of law journals into a bankable, mainstream villain for conservative and liberal audiences. In December, Netflix Inc.’s topical comedy show Patriot Act with Hasan Minhaj, which had previously tackled progressive bugbears such as the hazards of U.S. oil dependency, did a lengthy segment lashing out at Section 230. “This is a very difficult issue, and the solutions here aren’t simple,” Minhaj said. “But relying on the good faith of tech companies to regulate themselves? That ain’t working.” Meanwhile, an article on Breitbart referred to Section 230 as “the golden government handout” that’s allowed Big Tech to flourish, recommending reform of the law as a way to “curb Google.”

Over the years there have been attempts to reform Section 230. In 2013, 47 state attorneys general signed a letter beseeching Congress to allow states to pass laws contradicting the provision. The effort failed. Last year federal lawmakers succeeded at exempting cases involving online sex trafficking. In June of this year, Josh Hawley, a Republican senator from Missouri, introduced a bill that would require big tech companies to get the Federal Trade Commission to certify their political neutrality to qualify for the liability protection.

Such efforts to trim Section 230’s powers are likely to proliferate in the current political environment, in which pillorying the excess of Big Tech is suddenly a la mode. They’ll be met with well-funded resistance. The internet’s version of self-regulation might be imperfect, supporters argue, but the government’s would be far worse.

David Greene, an attorney for the EFF, says Section 230 is a victim of its own success. People look at the biggest web companies, such as Facebook Inc., and think they have so much money they should no longer receive the liability shield, he says, but the statute is necessary to protect smaller web services that might otherwise get crushed by unfair litigation. Any resulting bad behavior is an unfortunate byproduct of an otherwise effective law. “Any time you have a legal immunity, you’re going to have some people abusing it,” he says. “Think of the spousal privilege or something like that. It’s not necessarily surprising that there have been some bad effects.” For now, tech executives will continue to moderate the internet as they see fit.

At some point, the accumulation of “bad effects” can start to look more like a national emergency. In early August, following a mass shooting at a Walmart in El Paso, much of the ensuing national outcry focused on the deadly assault weapons—and websites—favored by domestic terrorists. On Aug. 5, two days after the shooting, the chief executive officer of Cloudflare Inc., a major web security company, announced it would be cutting off service to 8Chan, an online forum popular with white nationalists, including the alleged El Paso shooter. But to date, such piecemeal efforts at self-policing by the tech industry have proven largely ineffective, while individual sites are all too happy to invoke Section 230 to deflect legal responsibility for the havoc caused by their sickest users. Consider Gab.

Three years ago, Andrew Torba, a conservative entrepreneur who’d grown annoyed with progressive politics in Silicon Valley, founded a social media site called Gab. He positioned the service as a less restrictive alternative to Twitter, which, due to intense public pressure, had started to ban some of its more troublesome users. Word got around that Gab had no policies prohibiting hate speech. Droves of white nationalists set up shop, according to the Anti-Defamation League. (Gab does forbid speech not protected by the First Amendment, including calls for acts of violence against others.)

Reached by email in late July, Torba said he supports the efforts in Washington to investigate Big Tech for antitrust violations, but he dislikes Senator Hawley’s proposal to alter the internet’s immunity protection, which he calls “a powerful shield that allows us to protect our users’ free speech rights.”

Those users include Robert Bowers, a middle-aged Pennsylvanian who joined the site in early 2018 and started stewing in the fire sauce of hateful misinformation. On Oct. 27, he wrote a status update: “Screw your optics, I’m going in.” He then allegedly drove to a synagogue in Pittsburgh and murdered 11 people.

In the aftermath of the shooting, Pennsylvania Attorney General Josh Shapiro said his office would be investigating Bowers’s social media activity. Gab responded on the company’s Twitter feed with a knowingly dismissive taunt: “Have you ever heard of CDA 230?”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jillian Goodman at jgoodman74@bloomberg.net, Max Chafkin

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.