Some Fracking Sand Was ‘Revolutionary,’ or Maybe It Was Just Sand

Some Fracking Sand Was ‘Revolutionary,’ or Maybe It Was Just Sand

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- One by one, four employees of Fairmount Santrol were ushered into a cramped hotel conference room in Stafford, Texas, where they took turns explaining to their bosses why they thought the company was committing fraud. Some of the proprietary sand it was selling, they said, wasn’t so special.

Sand? During the shale boom, this simple-sounding stuff was a hot commodity. Drillers use sand and water deep underground to blast hydrocarbons from rocks in the process known as fracking, and Fairmount was selling specially manufactured sand, including one product that was touted as “revolutionary.” After the May 2017 meetings, nothing much changed in the way the business operated, attendees say. But others were watching, too. This summer the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission informed the company, now called Covia Holdings Corp., that it was considering enforcement action.

The company’s special sand was never a dominant product, but in a competitive industry its marketing campaign drew attention to Fairmount Santrol. The company merged with another to form Covia in June 2018. It became the biggest frack sand producer in the country. Houston investment bank Tudor Pickering Holt & Co. called the new company the “800-pound gorilla in the sand game.”

Some of its success, however, may have been based on a lie, according to interviews with former employees, multiple whistleblower complaints, and other court documents. They tell the story of Fairmount Santrol scientists running tests on the proprietary sand that found that some of the company’s most-hyped products didn’t perform all that much better than the stuff that came straight from the ground. But they saw a different story being pitched to customers.

“This fraud is particularly brazen because the company aggressively markets scientific testing to create the illusion of proven performance and reliability,” one whistleblower said in 2017 in a complaint to the SEC seen by Bloomberg. The next year another whistleblower blamed executives who “wholly adopted and reinforced a culture of covering up its lies without regard to who might suffer.”

Covia, which first disclosed the SEC’s inquiry in May 2019, says in a statement that Fairmount Santrol “fully investigated issues that were raised by employees” and determined there was no instance of fraud. It says it reported an employee complaint to the SEC in 2017 and has been cooperating with the regulator on its investigation into disclosures related to three products that have been discontinued.

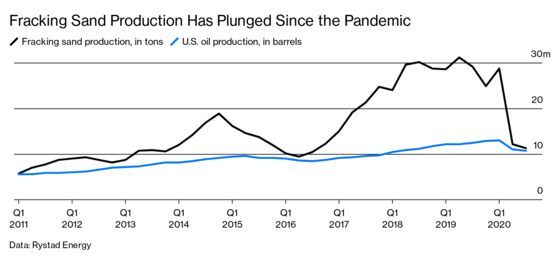

In the wake of the shale bust, many investors have discovered that some oil driller assets are not as valuable as they thought. The sand business has echoed that idea. For Covia, the SEC probe adds a layer of uncertainty on top of a broader economic drubbing. The sand industry peaked at about $4 billion in market value in 2018, according to researcher Rystad Energy, but it’s collapsed along with the 2010s fracking boom it fed. Next year the market for frack sand is expected to sink to half of what it was in 2019, Morgan Stanley says. The industry has suffered as the coronavirus continues to play havoc with oil consumption. Demand has plummeted, and Covia has suffered especially because many drillers grew tired of fancy sand and decided the cheaper, local type worked just fine. The company is one of four leading frack sand producers to seek bankruptcy protection this year, joining Vista Proppants & Logistics, Carbo Ceramics, and Hi-Crush.

In the 2010s, though, as fracking pushed the U.S. toward energy self-sufficiency, sand was a burgeoning business, and executives at Fairmount Santrol found a way to differentiate themselves. The company filed patents for products with names such as PowerProp. Its sales force went from company to company, hawking the new products to the biggest drillers. Drillers looking for a way to improve their output paid a premium at the time for specialized sand from Fairmount and other producers. At its peak price in the mid-2010s, a type of sand whose grains are coated with resin went for $250 a ton, a markup of $150 a ton over the cost of raw sand.

But inside Fairmount Santrol, scientists voiced their skepticism of some of the company’s products. By May 2017 it was enough of an issue that the company rented the hotel conference room a few miles from its suburban Houston offices and set up a folding table. According to attendees, who spoke on condition of anonymity because they didn’t want to jeopardize their job in the industry, four employees took turns speaking to a pair of executives.

The executives met with each employee for at least an hour, some for more than two. One of the people says it felt more like an interrogation than a fact-finding mission. A few weeks later, one employee, who’d received a negative work-performance evaluation two years before for questioning his bosses, says he received a message that the demerit would be removed from his file. Aside from that, Fairmount Santrol executives never talked about the meeting, he says.

The SEC issued a subpeona to Covia in March 2019, after an earlier informal inquiry in which the company voluntarily provided documents. Weeks later, Jenniffer Deckard, Covia’s chief executive officer, resigned. Covia says her departure was unrelated to the investigation. It said in a statement at the time that it was pursuing “a different direction” with its leadership. (Deckard was not one of the executives at the hotel meeting.) In June 2020, Covia filed for bankruptcy protection. Soon after, the SEC sent notice that its staff was recommending formal action against the company.

In a recent quarterly filing, Covia disclosed that the SEC had subpoenaed “certain former employees to testify regarding certain value-added proppants marketed and sold by Fairmount Santrol prior to the merger.” (Proppants are materials, including sand, that prop open rock fissures to keep oil flowing.) Agency staff have interviewed all four employees who filed complaints with the SEC, some more than once, according to a law firm representing the whistleblowers.

More often than not, notices such as the ones the SEC sent to Covia lead to formal action. Whatever happens, the company faces an uphill struggle. In its bankruptcy filing, Covia warned that after emerging from Chapter 11, it most likely won’t generate cash flow for the next two years unless creditors grant the company temporary relief from making interest payments. And sand, it turns out, isn’t such a precious commodity anymore: Drillers have plenty of places to get it. “Bankruptcies aren’t wiping out any capacity,” says Joseph Triepke, founder of Infill Thinking LLC and a former analyst at Citadel LLC’s Surveyor Capital. “It’s going to be a very miserable slog.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.