The Past and Present of Black-Owned Businesses in Seattle

The Past and Present of Black-Owned Businesses in Seattle

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- The One Year, One Neighborhood series follows small businesses in the Pike/Pine corridor in Seattle, the first coronavirus hot spot in the U.S., to get a sense of what cities will look like as they reopen.

Black-owned businesses have been particularly hard hit by the Covid-19 crisis. The number of active business owners in the U.S. fell 22% from February to April; the drop for black businesses was 41%. Even before the pandemic, the yawning racial wealth gap and persistent disparities in lending created a situation whereby the median black business in America had one-fifth of the revenue of the median white-owned company. With Seattle’s Pike/Pine corridor having become a hub for demonstrations over police brutality and systemic racism, I reached out to two local experts on minority entrepreneurship about some of the causes of these disparities, as well as ways to address them.

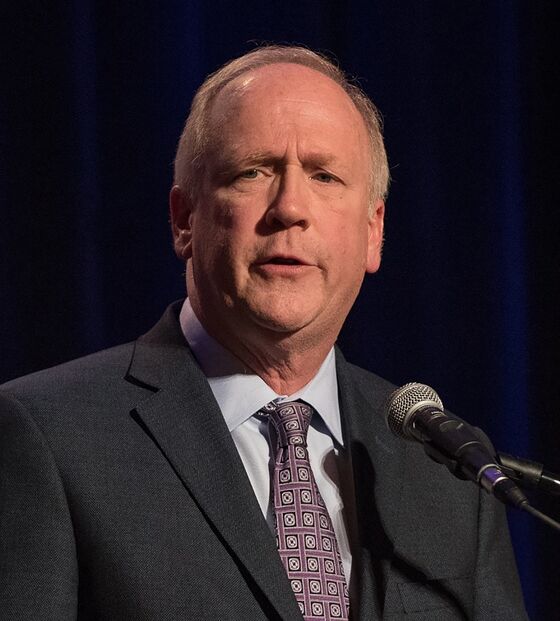

William Bradford recently retired from the University of Washington’s Foster School of Business, where he became the first black dean in 1994. A year later, he helped Michael Verchot start the school’s Consulting and Business Development Center, which supports businesses owned by people of color, women, and other underserved groups by helping entrepreneurs develop management skills, access capital, and exploit market opportunities through supply chain partnerships and contracts. The approach is the basis for the Ascend business-support network, a partnership with JPMorgan Chase & Co., that is present in 15 cities across the U.S.

I caught up with Bradford and Verchot earlier this week over Zoom. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

How has the history of racism affected the number, types, and success of black-owned businesses in the U.S.?

Bradford: Historically, black businesses were clustered in the black community, and they got their customers because those customers couldn’t get those same types of services outside of that community. The mom-and-pop stores, the barbershops, the beauty parlors, dry cleaners—the service group of black businesses—has really been the core from which the black business community has evolved. But from the ’50s, ’60s, ’70s and on, of course, black consumers have been able to buy from anywhere and everywhere, increasingly, so that competitive advantage of black businesses has been lost. But if you are competing in the general market, then you have to have the money, the management, and the markets in order to survive. So today, if we look at the black business community, in general, what we see is minority businesses have expanded their consumer base. But in just about every sector, they are in that weaker segment—less capital, fewer sales, less profits, fewer employees—though they have been growing in numbers.

In Seattle, a lot of those black-owned service businesses were historically in the Central District, a neighborhood just south of Pike/Pine. Why was that, and why have so many of them been getting displaced in recent years?

Verchot: It goes straight back to redlining. The official government policy [in Seattle and across the U.S.] restricted African Americans to living and buying property in certain neighborhoods. That was followed by an economic boom, with more people with significantly higher incomes moving in and displacing longtime residents, driving up property values, and driving up rents. African American businesses had their customer base being moved out because they could no longer afford to live in the Central District. That made it impossible to generate the revenue that was needed to stay viable. And so you’ve seen the migration to South King County [where the cost of living is lower]. This mirrors what’s happening in cities across the country.

What are some of the barriers that black entrepreneurs face that whites don’t?

Bradford: Well, we know that there’s an inheritance difference. There’s more wealth being passed down in white families than black families. The lower the wealth you have, the greater the barrier to business entry. At the same time, those who need additional wealth—and would ordinarily get the capital—there are biases in the financial system.

Verchot: There are real-life consequences here. Look at a company like Ezell’s Famous Chicken. They now have more than a dozen locations and are doing well. But they had a disproportionate challenge in getting loans approved and getting those loans disbursed. When they had a fire at their flagship store [in 1999], insurance companies took longer to reimburse them because they questioned the viability and the value of that company. Imagine if they didn’t have those hurdles—where they would be today.

Given everything we know about these disparities, do you think that black-owned businesses are going to fail at a higher rate than white-owned businesses during the pandemic?

Bradford: I do. A higher fraction of the minority businesses are in the sectors that are more heavily hit [such as restaurants, salons, and other consumer-facing industries]. But even in the other areas, minority business are the ones that are weaker from the start, in terms of having less capital and access to financing.

Verchot: We saw it in the dot-com bust. We saw it in the ’08-’09 financial crisis. You saw it after natural disasters in Houston and New Orleans. Right? I mean—again—if you if you start out smaller and weaker, and a storm comes, you get a bigger hit on you than others.

What’s going to change that pattern?

Verchot: We need corporations to step up and commit to more contracting opportunities with people of color. No. 2, we have to fix the education system. People of color still graduate high school at a lower rate, still go to universities—including ours—at a lower rate than the population as a whole. And then we’ve got to deal with access to capital. Less than 1% of venture capital dollars in the U.S. go to minority-owned businesses. Look at the Paycheck Protection Program— 150 or so publicly traded companies got PPP loans before minority businesses did. A lot of that is because minority businesses don't have relationships with banks. These are systemic issues that have been built over generations. These systems were created by humans, and humans can change those systems. It’s a question of: Do we have the will and desire to do so? I've been doing this work for 25 years. Bill’s been doing this research for a couple decades beyond that. I've yet to see any institution, whether it be private sector or public sector, set a goal for how we’re going to close the wealth gap. And so, if you're not setting goals, if you’re not measuring progress toward those goals, we are never going to make progress.

Bradford: I did a study for the National Urban League around the year 2000. It was about the state of the black economy. I said then that it was going to take—given the ratio and changes in black family wealth relative to white family wealth—over 100 years before there was parity. Over 100 years. The wealth gap has actually increased from 2000 to 2020. So my thinking is: We must come up with methods, processes, ways of thinking, to reduce the disparity. Entrepreneurship is one way. It’s not the only way, and it doesn't answer all the questions, but it can be one answer.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.