Mars Mission Is Next Step in Intensifying Middle East Space Race

The Middle East’s Mission to Mars

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- On the afternoon of Sept. 25 last year, Hazza Al Mansouri walked a gantlet of camera phone-wielding well-wishers at Kazakhstan’s Baikonur Cosmodrome. In step to his left were Russian commander Oleg Skripochka, a veteran on his third mission, and American flight engineer Jessica Meir, a first-timer like Mansouri. Their white-and-blue Sokol spacesuits made them appear hunched and ungainly, the communication caps covering all but a patch of face—in Mansouri’s case, dark eyes, a close-cropped beard, and most of a prominent forehead. Ahead of the astronauts were 160 vertical feet of a Soyuz MS-15 spacecraft and the elevator that would take them to its very tip.

Mansouri waved to his wife and three children. They’d said goodbyes earlier that day through the glass of the quarantine complex where astronauts spend two weeks before launch. Not being able to hug had been difficult, given the risks of what Mansouri was about to do. The previous October, a booster for another Soyuz craft, MS-10, had failed a few minutes after liftoff, forcing the crew to eject and parachute back to Earth in a shower of debris.

The MS-15 crew had observed the same superstitious traditions as all the others who’d taken off from Baikonur since the early 1970s: planting saplings on the avenue of trees, autographing their bedroom doors, watching the Soviet action film White Sun of the Desert. As Mansouri walked, he realized he and his crewmates looked just like the astronauts in photos he’d pored over as a child, except this time one of their suits—his—had the United Arab Emirates flag on its arm.

Shortly before 5 they were strapped in and starting prelaunch prep for the six-hour journey to the International Space Station (ISS). A playlist they’d compiled began piping through their headsets—another tradition, begun in 1961 by Yuri Gagarin before he became the first human to go to outer space. Mansouri’s choices included the Swedish-Lebanese singer Maher Zain’s Ummi (Mother), in tribute to his own. As he waited, he tried to focus on his training, his country, and the 64 successful Soyuz launches prior to MS-10.

Night fell, and banks of floodlights lit up the launchpad. At 6:57:43 the first stages ignited. Smoke vented, and the rocket eased from the ground on a great flame. Two miles up, the strap-on boosters exhausted their liquid fuel and fell away. Inside the crew compartment, it was only noise, vibration, and intensifying G-force—topping out, as the craft reached almost 18,000 mph, at four times the astronauts’ body weight. Their breath came only in gasps. It was beyond anything Mansouri had experienced as an F-16 pilot with the Emirati air force.

Roughly 62 miles up, the nose fairing jettisoned, and the crew could see outside. Earth’s curve was stark against the black of space. Mansouri stared and stared, until Skripochka interrupted. “Hazza,” he said. “You have your checklist.” There was a huge kick when the third stage stopped firing and fell away, then gravity retreated and blood rushed to their heads. Mansouri and Meir took out their pens and laughed in delight as they floated away.

Down below in Dubai, the most populous of the U.A.E.’s seven emirates, Mansouri’s face was being projected onto the Burj Khalifa, the world’s tallest building. At age 35, he’d become the third Arab to reach orbit and made the U.A.E. the 40th spacefaring nation. As a designated “spaceflight participant,” though, he would stay on board for just eight days, then return aboard a different vessel, the MS-12, with its crew. His trip had been purchased by the U.A.E. from Roscosmos, Russia’s space agency, for an undisclosed sum.

Arrangements like this, along with cost-lowering technological advancements and new commercial ventures, have made space no longer the sole preserve of great powers. Countries as small as the U.A.E., with a population of just under 10 million, can participate, too, if they have the desire for prestige and the resources to acquire it. Mansouri’s flight was one step in an ambitious national program that’s scheduled to send a probe to Mars between mid-July and mid-August and that has designs on making the U.A.E. a hub for space tourism. The country has moved ahead of neighboring Saudi Arabia to lead a regional jostle that also includes their common rival, Iran.

The two Gulf kingdoms have made space part of far-reaching plans to modernize and diversify their economies. Their moves in this direction, though, haven’t prevented persistent accusations of human-rights abuses at home and criticism of their ongoing involvement in Yemen’s civil war. The question, for many, is whether there’s real substance to the drive for space, or if it’s intended mostly to revise global perceptions.

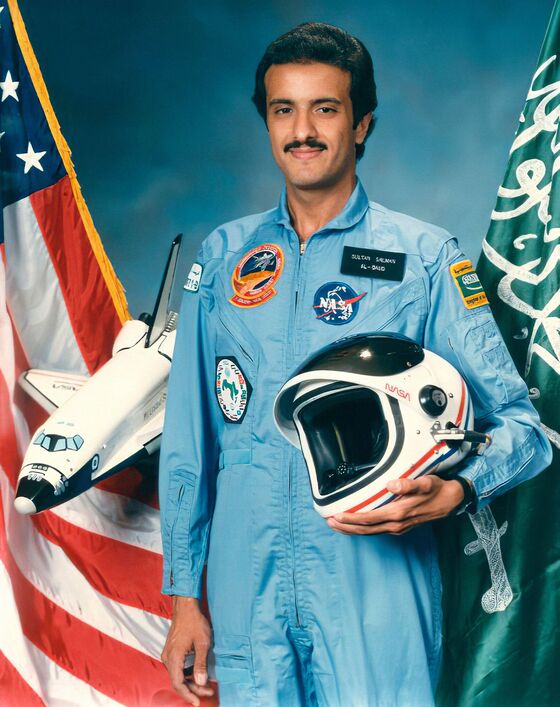

Saudi Arabia was the first Middle Eastern power to get an astronaut to space. In 1976 it took a leading role in the formation of multinational satellite communications company Arabsat, which put it in prime position the following decade when NASA’s space shuttle program started launching craft on behalf of private organizations and foreign states. The crew for these missions sometimes included a “payload specialist”—an astronaut not subject to the usual selection and training process. And so, in June 1985, when the Arabsat-1B satellite was scheduled for launch on the Discovery, one seat was allocated to Saudi Arabia.

The spot was filled by Sultan bin Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud. At 28 he was one of the youngest astronauts ever, and he lacked the advanced technical or scientific education NASA typically sought. He’d studied mass communications in the U.S., then worked at the Saudi Ministry of Information, where his duties had included accompanying athletes to the 1984 Summer Olympic Games in Los Angeles. He was a pilot, though, albeit a civilian one, and he spoke fluent English. He was also the second son of Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud, then governor of Riyadh and now Saudi Arabia’s king.

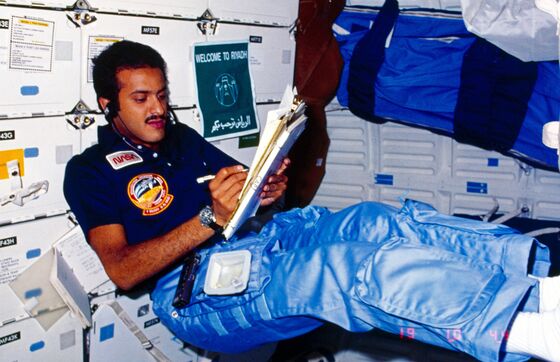

Sultan’s crewmates were five Americans and another payload specialist, from France. Publicity pictures show Sultan as thin and dashing, with blow-dried hair and a narrow mustache. As the first Muslim bound for space, he faced some unique theological challenges. How could he pray oriented toward Mecca, for example, if he was speeding over the planet at more than 17,000 mph? And the final weeks of training and first three mission days would fall during Ramadan. When should he fast if each 24-hour period contained 16 sunrises? After consulting with a religious scholar, he decided to wake up early during astronaut training for his predawn meal, then carry on as normal. In space he planned to fast on Florida time and pray facing Earth as best he could.

On launch day, he prayed on a plastic mat atop the steel launchpad gantry before boarding the shuttle. Alongside his regulation kit, he carried a Koran and an astrolabe—the early scientific instrument used to calculate the positions of celestial bodies—in recognition of the medieval Islamic astronomers who’d named many of the stars. In orbit he conducted experiments, handed out dates from Medina to his crewmates, and spoke with his father and King Fahd via video link for a Saudi TV broadcast. Upon return, he became an ambassador for his country and for spaceflight. He met President Reagan, gave lectures, and recorded a video message for the Live Aid concert. In space, Sultan told millions of viewers, “you see no wars, national boundaries vanish, and there are no famines.”

Saudi leaders discussed with NASA the possibility of placing an astronaut on the shuttle every two years, but those conversations ended after the Challenger disaster in January 1986. The shuttle program was grounded for almost three years, and the U.S. announced it would leave the business of launching commercial satellites to the private sector.

The Saudi space program carried on less obtrusively into the early 2000s. The country started building its own satellites at the King Abdulaziz City for Science and Technology (KACST), remaining the clear leader in space among the Gulf powers until 2004, when its main geopolitical rival, Iran, created its own space agency. Iran put a Russian-made satellite in orbit the following year, then followed it with a domestically built satellite, as well as mice, turtles, worms, and a couple of monkeys. The regional race was on.

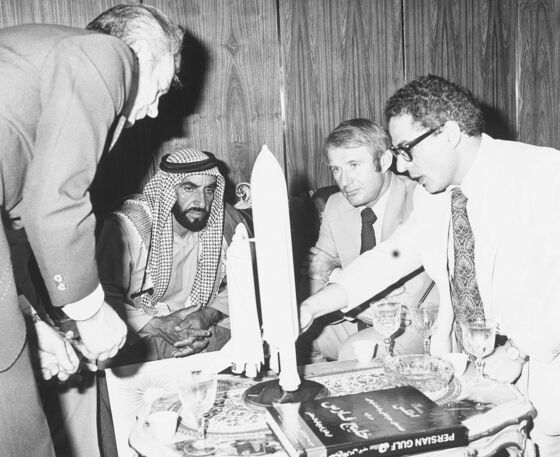

The U.A.E. has harbored space dreams almost since it was formed. In February 1976, five years after Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan united the Trucial States, he met the three crew members of Apollo 17. The astronauts presented Zayed, by then the U.A.E.’s president, with a fragment of moon rock and a model of the space shuttle. A monochrome photograph captured the astronauts sitting at an ornate coffee table with him, explaining the craft.

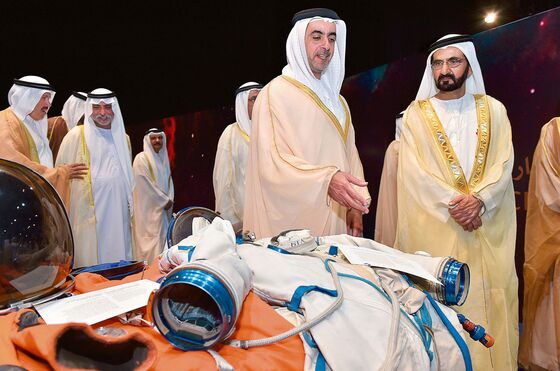

It wasn’t until after Zayed’s death in 2004 that the kingdom began pursuing his ideas in earnest. When billionaire Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum became the Emirates’ vice president and prime minister a few years later, Dubai was experiencing a building boom, drawing in foreign bankers and executives eager to take advantage of favorable tax and regulatory policies. Space technology, Emirati rulers noted, would help the U.A.E. decrease its reliance on oil and build its international standing. In 2006, Maktoum founded a space center, subsequently named after him. Three years later the facility unveiled DubaiSat-1, a largely Korean-made satellite. In 2013 came DubaiSat-2, this time with labor divided evenly between the two countries, and then, five years later, KhalifaSat, constructed entirely by Emiratis.

KhalifaSat, according to Omran Sharaf, a project manager at the Mohammed bin Rashid Space Centre, was the U.A.E.’s “final examination when it comes to Earth observation missions.” I met with Sharaf and Sarah Al Amiri, the U.A.E. minister for advanced sciences, on the 40th floor of a government office in Dubai. Both are in their mid-30s, charming, and staggeringly high-achieving—exactly the image the Emirates wishes to project. Sharaf recalled sitting at home in November 2013, the evening before DubaiSat-2 launched, when the space center’s director general called with an unexpected question: “Can you look into Mars?” Sharaf replied confidently: “Sure.” Seven weeks later, Maktoum told Sharaf and Amiri he wanted to celebrate the U.A.E.’s 50th anniversary with a major achievement. This time, Amiri said, the question was more direct: “Can we get to Mars?” The answer was “an informed yes.”

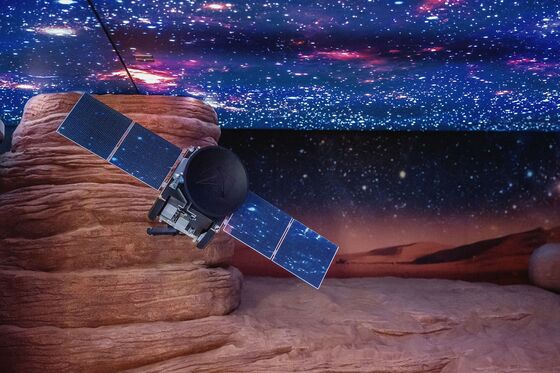

The Emirates didn’t even have a space agency yet, but it founded the UAESA in the summer of 2014, at the same time as it announced its intention to have a probe orbiting Mars by Dec. 2, 2021. The mission, Maktoum said, would herald a reprisal of the Arab world’s leading role in advancing human knowledge. Sharaf became the project manager and Amiri the science lead of a team of 200 Emirati academics and scientists. Their task was to build a craft, named Al Amal (“Hope”), that could study changes in the Martian atmosphere for at least two years. The deadline was already intimidatingly close. A mission so complex would normally take at least a decade to develop. Plus, the launch window during which Earth and Mars are most proximate comes only once every two years, and the journey required seven months, leaving several weeks beginning in mid-July 2020 as the only possible window.

In December 2017, with the Mars mission entering its manufacturing phase, Maktoum announced on Twitter that the U.A.E. would also begin an astronaut program. Mansouri started his application that day. He’d grown up a sci-fi-loving child in the remote deserts south of Abu Dhabi, where he could gaze up at a night sky clear enough to spot the occasional comet. In fourth grade, he’d seen a picture of Prince Sultan in a textbook. “It was amazing because he was Arabic,” Mansouri says. The only other Arab to have left Earth was a Syrian, Muhammed Faris, who flew on a Soviet mission in 1987.

As he got older, Mansouri dedicated his life to reaching space. Many early astronauts had been pilots, so Mansouri became one, too, attending military college and going to the U.S. to learn to fly F-16s, then qualifying as an instructor and an air show team member. The monochrome picture of Sheikh Zayed and the Apollo crew hung in his squadron house.

The first cut for the U.A.E. astronaut program brought the prospect pool down to 95, from 4,000. After a few more rounds, there were just nine—a mix of nuclear scientists, engineers, pilots, and doctors. One night in August 2018, Mansouri got a call from Salem Al Marri, the MBRSC’s deputy director general, who, after a preamble so long Mansouri thought he was being let down politely, gave him the good news. Sultan Al Neyadi, a military engineer, would join him as a reserve. Their training included a three-day survival exercise in the Kazakh wilderness. “I saw them afterwards,” Marri says with a laugh. “I mean, it was cold. They smelt like burnt firewood, they’re all black everywhere from the smoke.”

Three days before launch, Mansouri spoke with Sultan on the phone, thanking the prince for inspiring him. Mansouri’s flight cargo included 30 Al Ghaf seeds for planting back on Earth, jewelry and toys belonging to his family, and some freeze-dried Emirati meals. Just about every second of his time in space delighted him: the disruption to his perception of up and down, the view out the window by his berth, the behavior of water droplets in zero gravity. “Using the toilet is a different story,” he says, giggling. From orbit he conducted 16 experiments, gathering data on the effects of microgravity on genes, cell growth, and seed germination. He also gave the first Arabic-language tour of the ISS for later release online. On his last day aboard, he slept only the mandatory four-hour minimum so he’d miss as little as possible. He returned home a hero.

The Emirates’ focus is now on the Al Amal mission. The probe—a 3,300-pound, 2.9-meter-tall cuboid aluminum structure with three folding solar panels attached—shipped to its Japanese launch site in April, weeks earlier than planned because of the pandemic. If the mission succeeds, the UAESA will become just the fifth agency to reach Martian orbit. The probe will send back images and other data that will be made freely available to at least 200 research institutions around the world. From there, according to the agency’s director general, Mohammed Nasser Al Ahbabi, plans include a spaceport, tourism, and a Mars colony by 2117.

Critics of the U.A.E.’s space program point out that its technological achievements have helped gloss over the country’s dismal human-rights record. Emirati women still require permission from a male guardian to marry, for example, and stoning and flogging remain legal punishments. In March, a U.K. High Court ruled that Maktoum had orchestrated the kidnapping and forcible return of two of his daughters after they’d tried to escape him and that he’d conducted an intimidation campaign against his former wife. (In an appeal to keep the findings out of the public domain, the sheikh said he hadn’t been able to participate in the court’s fact-finding process and so the judgment “inevitably only tells one side of the story.”)

Devin Kenney, who researches the Gulf region for Amnesty International, describes aspects of the Emirates’ recent outward-facing initiatives as a “marketing strategy directed to the world.” He adds: “Any speech within the U.A.E. that’s directed to critical self-improvement instead of just lavishing praise on this very shiny, fancy, glitzy, rich, advanced moneydrawing technological image will get you in trouble, severe trouble—up to and including horrific torture.” (A press office for the U.A.E. Ministry of Foreign Affairs didn’t respond to emailed requests for comment.)

Since March 2015, the U.A.E. and Saudi Arabia have also been part of the coalition of Arab states, led by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, Sultan’s half-brother and the de facto ruler of the Saudi state, that’s intervening in a brutal civil war in Yemen. The conflict is one of the world’s worst humanitarian crises, with more than 100,000 people killed and millions in need of aid. Coalition airstrikes have hit weddings, hospitals, school buses, fishing boats, and mosques, causing more than 8,000 civilian deaths, according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project. Detainees of the coalition and allied Yemeni forces have been subjected to torture and sexual violence, according to the United Nations.

When Prince Mohammed, known as MBS, took over day-to-day leadership of Saudi Arabia in 2017, at age 31, he styled himself a reformer and modernizer. Central to his ambitions was his Vision 2030 plan, which sought to economically diversify and develop the kingdom. He ended a ban on women driving, weakened the male guardianship system, allowed gender-mixed public concerts, and embarked on a U.S. goodwill tour. At the same time, MBS jailed rivals, opponents, and activists, including some of those who’d campaigned for women’s right to drive, and carried on the campaign in Yemen. Then, in October 2018, a kill team asphyxiated and dismembered journalist and government critic Jamal Khashoggi inside Saudi Arabia’s Istanbul consulate. U.S. intelligence agencies concluded that the crown prince had ordered the hit. (MBS denied this but said he takes responsibility for the murder.)

Less than three months after Khashoggi’s assassination, a royal decree established the Saudi Space Agency. Prince Sultan became its head, after a decade atop the tourism ministry. His new role would include overseeing operations and coordinating MBS’s space initiatives with counterparts in the U.S., Russia, France, and elsewhere.

I met with Sultan in Riyadh in April. KACST had constructed a colossal and still-expanding facility on the city’s western outskirts, but the space agency hadn’t yet been assigned a headquarters, so the prince was working out of an unused section of the King Salman Center for Disability Research. A photo of the Earth, viewed over the lunar horizon with Saudi Arabia prominent, hung on the wall. It had been taken during China’s Chang'e-4 mission, to which KACST had contributed.

Sultan arrived with a large entourage. Now in his mid-60s, he was still immediately recognizable, though his face is broader and his mustache grayer than in his 1980s NASA publicity pictures, and his hair was concealed beneath a traditional headdress. An aide cautioned that the interview was to be “only about space.” Khashoggi’s murder was still making headlines, and I’d picked up my visa from the consulate where he’d been killed.

The prince spoke like a man who’s rarely interrupted, listing the many merits of the Saudi people (“innovative,” “very modern,” and “open-minded, regardless of anything you see or hear”) and musing wistfully about spending a year in South America. He spoke of summer plans to join a bush pilot operation for 10 days and of his desire to track down Chuck Yeager, whose hand he’d once shaken. He told me about a blood feud in which he’d interceded 17 years ago and predicted that Saudi Arabia would one day win the World Cup.

When he spoke about the agency’s plans, he grew serious. There would be more Saudis in space, he said. Inspiring Saudi youth was important, but he wanted to see scientists flying, too. “What is the return for our country? It’s very critical that we don’t do anything just for flag-waving.” To that end, he planned to found a space business entity. “We are focusing on being an incubator. I think any country that’s going to go anywhere in the future has to really focus as much as possible on entrepreneurs.” It was the language of NewSpace, opportunity and startup culture in service of humankind—entirely consistent with MBS’s Vision 2030 rhetoric.

Saudi Arabia’s space program, like the U.A.E.’s, is sometimes viewed as having a whitewashing effect. Tamara Cofman Wittes, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and former U.S. deputy assistant secretary of state, says that, whether it’s moonshots or the planned coastal “smart city” of Neom, big technology projects are for the Saudi government partly “about creating an image of your country as forward-looking and progressive, and attracting investors.” She points out that a conference highlighting Neom took place in Riyadh soon after Khashoggi was murdered. (A foreign-media liaison office for the Saudi government didn’t reply to an emailed request for comment.)

There’s also growing evidence that space will play a role in the battle for military dominance in the Gulf. Iran’s satellite program has in recent years suffered a series of failures, including a launchpad rocket explosion, but in April, Tehran claimed to have put its first military satellite in orbit. The U.A.E., for its part, has purchased Thales-manufactured high-resolution military observation satellites ostensibly designed to monitor its borders. At one point during my interview with Ahbabi, the UAESA director general, he described space as “the fourth domain of power,” prompting two aides to shift uncomfortably in their seats and clear their throats in an apparent attempt to redirect the conversation.

As for Sultan, he refused to be drawn into a discussion of two imaging satellites Saudi Arabia is known to have launched in 2018 or on the potential military applications of space technology. A representative didn’t reply to subsequent requests for information.

Less than three weeks after I left Riyadh, authorities executed 37 people in a single day for “terrorism-related” offenses, following trials that lawyers and rights groups called deeply unfair. Most of the condemned were publicly beheaded, and the body of at least one was displayed afterward. In the ensuing months, the Saudi Space Agency signed a number of agreements to collaborate with its international counterparts, including the UAESA, and unveiled plans to establish a national training center. This March saw the war in Yemen enter its sixth year, with little sign of abating.

Despite the surrounding politics, those involved in the Saudi and Emirati space programs still see their work as a pursuit of scientific advancement and international cooperation. Nine days after Mansouri returned from the ISS, he was welcomed in Abu Dhabi by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, Sheikh Zayed’s son. Al Nahyan had a model Soyuz rocket and a request: Could Mansouri explain its operation and join him in re-creating the 1976 picture of his father with the U.S. astronauts?

They sat down at an ornate table for what Mansouri calls one of the most amazing moments of his life. He later posted the photo on Instagram, side by side with the old one. “Yesterday, we witnessed the achievement of the world … Today, the world celebrates our achievements,” he wrote. “Zayed’s ambition is creating a new history.”

Read next: Elon Musk Speaks Frankly on Coronavirus, SpaceX, and Rage Tweets

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.