The Four Biggest Ways That Robinhood Changed Investing

The Four Biggest Ways That Robinhood Changed Investing

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Not so long ago, before the pandemic took hold in the U.S., it seemed like standalone retail trading firms were a thing of the past. E*Trade, the brokerage that gained notoriety in the dot-com boom, sold itself off to Morgan Stanley. Charles Schwab Corp. and TD Ameritrade, two of the largest brokers, inked a deal to combine in November 2019, forming a single supermarket for everything from financial planning to exchange-traded funds.

But a new brokerage boom was just about to begin. Robinhood Markets Inc., the company that championed commission-free trading, is set to make its stock market debut on Thursday. The initial public offering puts an exclamation point on more than a year of flourishing retail trading action, which featured a series of unexpected antics: Ordinary investors charged in to buy shares of bankrupt companies such as Hertz Global Holdings Inc., banded together online to bid up the price of such “meme stocks” as GameStop Corp. and AMC Entertainment Holdings Inc., and piled into cryptocurrencies and options. Robinhood was far from the only forum for this kind of trading, but its colorful, easy-to-use mobile app, its success at drawing in young people, and its breakneck growth made it part of the lockdown-era zeitgeist.

To its critics, Robinhood helped make investing seem like a game, pushing novices to take risks. The company says it’s made investing available to more people and less forbidding, and that hyperactive traders are a small slice of its customer base.

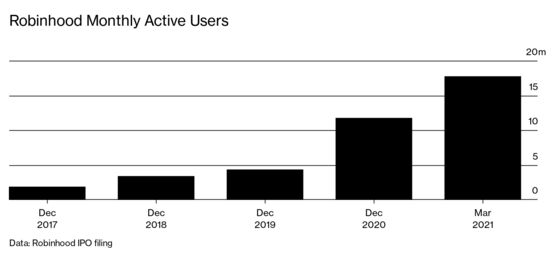

Robinhood’s IPO brings its story full circle. It had an estimated 22.5 million funded accounts at the end of June, more than double the level of a year earlier. For the IPO it set aside up to 35% of its shares for its own users, in an effort to convince customers of Robinhood, the app, that they can also share in the fortunes of Robinhood, the company. Whatever comes next for the stock, Robinhood has made an indelible print on its industry and on investors:

• Investing became free ...

To be clear, Robinhood wasn’t the first company to abandon commissions. Bygone broker Zecco.com offered customers 40 free stock trades per month when it was starting out in 2006, but it scaled that promise back the following year. Robinhood’s timing, in contrast, couldn’t have been better.

When Robinhood launched trading in 2015, other brokerages charged $5 to $10 for a single transaction. It charged nothing and carried no account minimums. Other Robinhood features, such as giving customers a free stock and showing them what their peers were buying, gave newbies an entry point. The popularity of Robinhood’s app helped push rivals to go to zero. At this point, retail investors don’t pay to place stock trades on any major platform.

Brokerages can still make money on free trades: Behind the scenes, they route orders to be executed by trading firms that earn money on tiny differences in market prices. These firms pay brokers for sending orders their way. Robinhood earned three-quarters of its revenue through such transaction-dependent payments in 2020.

• … and, more importantly, bite-sized.

Robinhood also popularized, but didn’t invent, the idea of fractional shares, which allow investors to buy just a piece of a stock with as little as $1, instead of having to shell out, say, increments of $3,626 for each share of Amazon.com Inc. Established brokers increasingly recognize the value of catering to traders without much to spend. Fidelity Investments Inc., for example, unveiled a program that allows teenagers to trade fractional shares.

Along the way, the industry has gone from being a battle between high-cost and low-cost providers to a duel between two kinds of low-cost models. Before the no-fee brokerage era, investing was already getting cheaper and easier. The Vanguard Group made a mission of lowering costs on its index-tracking funds, making it possible for anyone to buy the entire S&P 500 while paying a fraction of the fees money managers and old-fashioned stockbrokers used to charge. Robinhood’s low-cost model is something different. It doesn’t require diversification or indexing. It lets small, self-guided investors buy and sell single stocks all day.

• It helped make risky trading mainstream.

Robinhood doesn’t sell financial planning or retirement accounts or mutual funds, though it does offer the exchange-traded funds available at any broker. In an interview last year with Bloomberg Businessweek, Chief Executive Officer Vlad Tenev said that he sees plenty of Robinhood customers using fractional stock shares to make recurring investments in the market. Still, it’s an app built mainly for trading: stocks, cryptocurrencies, and options.

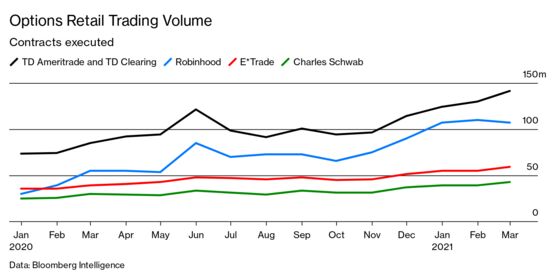

That last one is notable. Options are essentially a way to bet on a stock with leverage, amplifying both potential gains and losses. Again, almost every brokerage offers options—and the top options platform is TD Ameritrade. But Robinhood’s app helped make them more accessible. And the broker’s growth coincided with the boom in raucous online forums such as WallStreetBets, where users talked up their options strategies for GameStop and the like.

Josh White, an assistant professor of finance at Vanderbilt University, recalls what setting up options capabilities at some brokers was like before Robinhood existed. After you applied, a representative might call on the phone to follow up. Today, a few taps can lead to options trading approval on Robinhood. “That’s my biggest concern,” White says. “They certainly made it easy to become qualified.”

Regulators deemed it too easy at times. Robinhood agreed to pay a regulatory penalty of almost $70 million for a range of alleged infractions including lax oversight of options trading permissions, which were filtered through an automated system, according to the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority. A Robinhood spokeswoman said at the time the firm had invested in building its customer support and compliance teams. Separately, the company is still grappling with the fallout from the death by suicide of a customer who may have misunderstood what he owed in an options transaction. Tenev apologized to the man’s family and Robinhood made changes to its options platform, including introducing phone-based support for those products.

• It brought Silicon Valley to Wall Street.

Robinhood showed that with a well-designed app, you could sell investment products to the same young, not-necessarily-rich consumers tech companies have specialized in reaching. Other startups including brokerages EToro and Webull Financial LLC now have their sights set on a similar market. The median Robinhood investor is 31, and about 70% of the company’s assets under custody come from customers aged 18 to 40. Now Robinhood’s backers are counting on its ability to turn those customers into long-term investors.

Tenev said in the company’s roadshow that Robinhood is open to the idea of providing retirement accounts, for example. Whether investors want such products from their trading app is another question. “Robinhood created access to the category for a tremendous number of people,” says Hugh Tallents, senior partner at consultancy CG42. “But there’s a moment when you graduate from access to a true financial partner.”

Read next: Ten Company Stocks to Watch in Q3 2021

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.