Road Deaths Are Soaring Even as Americans Are Driving Less

Road Deaths Are Soaring Even as Americans Are Driving Less

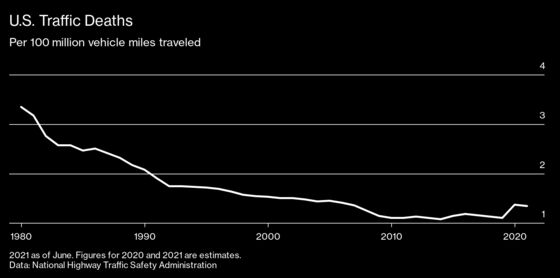

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Data on U.S. traffic fatalities in 2020 shocked safety advocates: At a time when people were driving less, deaths jumped. In fact, they were higher last year than in any year since 2007.

And 2021 could be even worse. The federal government estimates that 20,160 people died in motor vehicle crashes in the first half of this year. That’s an 18.4% increase from the same period in 2020.

“This is a crisis,” Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg said in a statement when the numbers were released on Oct. 28. “We cannot and should not accept these fatalities as simply a part of everyday life in America.” Buttigieg promised that by January, his department will come up with a “first-ever” federal strategy for improving road safety.

Initially safety experts blamed the rising deaths on reckless drivers speeding down empty roads, with most people at home because of the pandemic. It seemed that congestion, though annoying, was also a major road safety feature, forcing drivers to slow down. But when traffic started to return this year and more people were driving, deaths increased again. “This is our other national pandemic—traffic crashes,” says Pam Shadel Fischer, senior director for external engagement at the Governors Highway Safety Association.

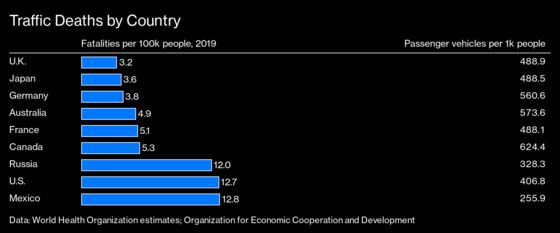

Experts don’t know what’s causing the surge, but there are plenty of candidates. Since the pandemic began, people are speeding more and wearing seat belts less, according to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA). Vehicles are getting bigger. State lawmakers are making it legal to go faster. U.S. regulators have been less aggressive than those in other countries on vehicle safety requirements.

The spike has undermined two long-held assumptions in the transportation industry, says Beth Osborne, director of the advocacy group Transportation for America. First, it was believed that more driving would mean more fatalities, and if driving went down, road deaths would decline, too. Second, the conventional wisdom has been that almost all crashes are the result of human error, so the solution is improving drivers’ behavior. “At least one of our assumptions has been proven wildly wrong,” she says.

That’s bolstering the case Osborne and other safety advocates have been making for years: that changing street design is at least as important as educating drivers. “If I see a very wide-open road, my natural inclination is to drive fast,” Osborne says. “Highways are designed specifically to allow for fast driving. What we’ve done is take that highway design and apply it to roadways that serve local developments, where there are lots of conflicts.”

A growing number of cities, including Austin, Fort Lauderdale, and New York, are redesigning their streets. They’re narrowing vehicle lanes, adding features that force drivers to reduce speed for turns, and protecting pedestrians with “bulbed out” sidewalks at intersections and islands in crosswalks.

Another major concern is the vehicles themselves. For a half-century, the federal government’s main safety focus has been protecting the driver and other passengers inside the vehicle when it crashes. But that focus ignores the safety of whomever the vehicle is running into, such as passengers in another car or pedestrians, and that’s worrisome as the size of vehicles increases. Americans now buy about twice as many SUVs as sedans, a remarkable development considering that SUVs first outsold sedans in 2015. High school physics shows why that can be a problem: A vehicle’s force is its mass times its acceleration.

Both are increasing for new cars. The average weight of new vehicles hit 4,156 pounds in the 2019 model year, a record. The average power of vehicles set an all-time high that year (the most recent for which data are available) as well, climbing to 245 horsepower. Those trends are only going to increase as automakers roll out more electric vehicles, which are heavier and more powerful.

“We know from research we’ve done that a greater amount of horsepower equals higher speeds traveled, and we know higher speeds traveled leads to a higher number of crashes with higher severity,” says David Harkey, president of the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety.

The NHTSA, the federal agency in charge of vehicle safety, has faced plenty of heat from critics including researchers, consumer groups, safety advocates, and members of Congress. They say the agency uses outdated and easy-to-pass crash ratings, hasn’t adequately regulated infotainment systems or Tesla Inc.’s autonomous driving features, has been too reluctant to issue recalls, and has failed to issue 13 safety rules required by Congress.

Even the auto industry is fed up. The Alliance for Automotive Innovation, which represents major automakers, wants the agency to update its new-car rating system for the first time in a decade. To start it wants the feds to incorporate new technology—lane departure warnings, automated braking, pedestrian detectors, automatic high beams—into the ratings.

Adding to the frustration is that the NHTSA hasn’t had a permanent leader for almost five years. President Joe Biden has called for safer infrastructure but took until mid-October to nominate Steven Cliff to head the agency. Cliff, a former environmental regulator in California, is the current deputy administrator. Former agency officials have complained that the agency has long been understaffed, particularly as measured against the deep-pocketed automakers it regulates. The NHTSA and the U.S. Department of Transportation didn’t respond to requests for comment.

The infrastructure bill that passed Congress requires the NHTSA to test cars for their risk to pedestrians. It also requires states to do road safety assessments. A multipronged strategy is needed to make U.S. roads less deadly, one that looks at vehicles, road design, speed limits, and behavior, as well as education and enforcement, says Jennifer Homendy, chair of the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB). Currently many pieces of the system work against one another, she says.

The NTSB, an independent government agency, is perhaps best known for taking over investigations to determine why planes crash. The U.S. commercial aviation industry has become the gold standard in safety: It hasn’t had a fatal crash in 12 years. Many of the lessons that helped improve safety in that industry could also apply to roads, Homendy says.

In aviation “they looked at where our risks were and how to address them,” she says. “Is it the plane? Is it the environment it’s operating in? Is it the pilots? Is it [the government’s] operations? It was looking at the whole picture to see where the investments in safety needed to occur.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.