Trouble Brews for American Companies That Gorged on Cheap Credit

Trouble Brews for American Companies That Gorged on Cheap Credit

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- The collateralized loan obligation, or CLO, is one of those funky creations of Wall Street wizardry that have been around for decades. Just like its close cousin, the much-castigated collateralized debt obligation, it’s a tool used to package a bunch of high-risk debt together—mortgage bonds for CDOs, corporate loans for CLOs—so they can be easily sold to investors hungry for juicy returns.

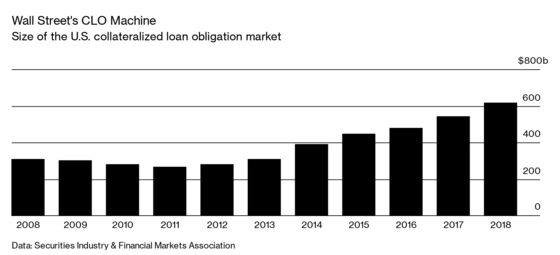

Unlike the CDO, the CLO made it through the financial crisis largely unscathed and has boomed in the decade since. Fueled by the unprecedented $3.5 trillion wave of private equity buyout deals during the past decade, and rock-bottom U.S. interest rates that only stoked investors’ willingness to gamble on riskier assets, the CLO market has more than doubled since 2010, to $660 billion. By providing abundant cheap funding to the less creditworthy end of the market, it’s helped grease the wheels of the longest economic expansion in U.S. history.

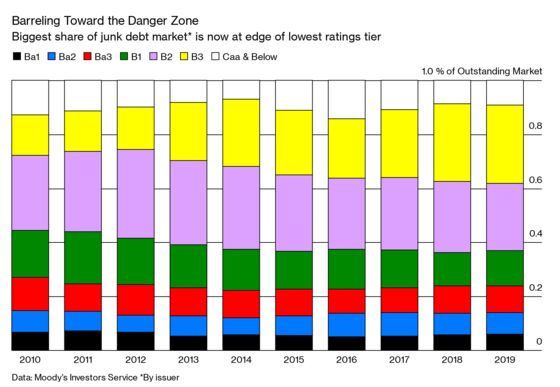

But as odds of a recession in 2020 grow, ratings downgrades could cause a stampede of selling by CLOs, potentially cutting off scores of companies from additional credit, preventing them from refinancing their debt, and threatening their survival. Almost 40% of issuers of junk-debt (which includes leveraged loans) are now rated B3 and lower, according to Moody’s, a record high..“If there’s no price support for lower-rated loans, that will be reflected over time in new issue and refinancing markets, which may mean the lowest-quality borrowers lose access to capital markets,” says Andrew Curtis, the head of Z Capital Group‘s credit arm, which manages CLOs and other funds. Volatility in the market could spill over into the high-yield bond market and even send ripples into the broader economy that could deepen or prolong any recession.

The heart of the problem is the very same phenomenon that fueled the growth in the market in the first place: those ultralow rates. A CLO begins with what Wall Street calls a leveraged loan—basically, a loan that piles more debt on a company’s balance sheet than most traditional lenders would tolerate. A few hundred of the loans can be packaged together into a CLO. The CLO then offers investors bonds with different levels of yield and risk, backed by the loans.

What makes it all work is investors hungry for yield in a world where interest rates have been at historic lows for 10 years and trillions of dollars of debt with negative yields. Now, the same low rates that have fueled the market are creating problems for it. The reach for yield has allowed private equity barons to load debt on the companies they acquire to boost returns on their buyouts. Corporate borrowers have loaded up on debt too. That’s left CLO managers with little choice but to buy riskier loans.

An alarming number of leveraged loans—29% by some estimates—are rated B- by S&P Global Ratings or B3 by Moody’s Investors Service. For both ratings companies, that’s just one rung above CCC, the very lowest tier before default. Most CLOs are contractually limited to keeping no more than 7.5% of their money in debt rated CCC or lower. So, should the economy slump, as a growing number of analysts fear, and more leveraged loans are downgraded, the CLO managers will be in a bind: either unload that debt, and fast, or risk tripping ratings triggers that prevent them from making some payments to their investors.

CLOs own about 54% of all leveraged loans outstanding. With so much debt at the cusp of the triple-C danger zone, CLOs have already started avoiding lower-rated debt and—in the case of such companies as LED lightbulb maker Lumileds, inkjet recycler Clover, and video production company Deluxe Entertainment—selling loans that appear to be headed into triple-C purgatory. “There is no natural place for B3-rated loans when they begin to struggle,” says TCW Group Inc. Managing Director Drew Sweeney. “If a company is downgraded from B3 to CCC, you do see the market immediately react because CLO managers want to sell.”

Lee Shaiman, executive director of the Loan Syndications and Trading Association, an industry trade group, isn’t concerned. “We do not see liquidity pressures emerging from CLOs,” he says. “They are not forced sellers of CCC loans. If CLOs choose to sell CCC assets, there is a large pool of willing buyers.”

Who are those buyers? It’s a short list. Money managers without the same constraints—such as leveraged loan mutual funds—might swoop in. But investors have withdrawn money from those funds for 47 of the last 48 weeks, largely eliminating what had been a reliable source of demand for corporate loans.

Even fund managers with cash to invest in distressed loans have been increasingly reluctant to step in, because an increasing share of corporate borrowers don’t disclose their financial performance publicly. In other words, when existing lenders catch wind of financial trouble at a leveraged loan issuer and move to sell the debt, the only potential buyers who can look under the hood to assess the condition of the company are their counterparts who already hold the debt. And they, of course, aren’t interested in buying more. “It’s like going online, trying to buy a car without being able to see if there’s rust in the undercarriage,” says Stephen Ketchum, chief investment officer of Sound Point Capital, an asset manager that sells CLOs.

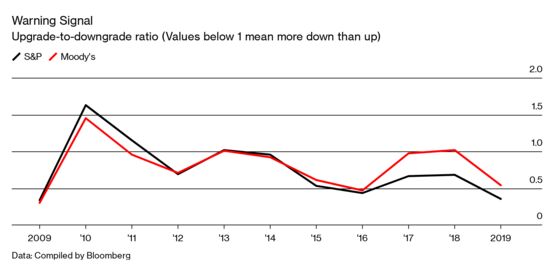

The situation’s only getting worse as downgrades by S&P outpace upgrades by the most since 2009. And the ratio for Moody’s isn’t far behind. Companies rated near or in the triple-C zone have $508 billion coming due in the next five years, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

Deluxe Entertainment Services Group Inc. shows just how quickly liquidity in the leveraged loan market can evaporate. A postproduction media services company for the film industry, Deluxe has struggled with a changing digital media landscape in Hollywood and an increasingly burdensome debt load. But with tens of billions pouring into the leveraged loan market and a CLO machine cranking out deal after deal, Deluxe and its owner, Ronald Perelman’s MacAndrews & Forbes, had little trouble in recent years raising new debt to keep the company afloat.

Deluxe refinanced its debt in 2014, getting enough demand from investors that it was able to upsize its loan by $35 million, to $605 million, and cut its interest rate by a full percentage point. Two years later, the company returned to the market for an additional $75 million, and it tacked on $200 million more in 2017 to refinance some of its other debt.

But as Deluxe’s problems mounted, its cash thinned. After an unsuccessful effort to sell its creative services unit, it turned to its existing lenders, who agreed to back a $73 million loan in July. That’s when it got ugly. The news of the abandoned sale and new debt caused the value of Deluxe’s loan—with $768 million still outstanding—to plunge from 89¢ on the dollar to less than 40¢ in some 24 hours. Within about a week, S&P downgraded its rating by three notches, to CCC-. The downgrade blocked some existing CLO lenders, bound by the 7.5% limit, from fronting additional cash. On Oct. 3, the company filed for Chapter 11. The existing loan now trades at less than 10¢ on the dollar. Deluxe said in a statement that “We appreciate the support we have received from our lenders throughout this process and look forward to completing the refinancing shortly.”

The world’s financial watchdogs are taking notice. The Financial Stability Board, set up in the aftermath of the financial crisis, is investigating. In an October letter to G-20 central bankers and finance ministers, it singled out CLOs and leveraged loans as an area for concern. The market’s heightened complexity and opacity, it said, make it “difficult to assess potential spillovers and risks.” —With Adam Tempkin

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Eric Gelman at egelman3@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.