Rising Cape Town Gang Violence Is Yet Another Legacy of Apartheid

Rising Cape Town Gang Violence Is Yet Another Legacy of Apartheid

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- While Cape Town is South Africa’s top tourist attraction, few of its 1.7 million annual foreign visitors venture beyond the iconic areas around Table Mountain to the Cape Flats, a mishmash of sandy, windswept neighborhoods filled with low-rise apartment blocks and shacks designed by the apartheid regime to keep the city’s black and mixed-race residents out of view. Decades of government neglect and high unemployment have contributed to a proliferation in gang activity there. Police estimated in 2013 that there are 100,000 gang members in the city of 4 million people.

Just 12 miles from Cape Town’s beaches, five-star hotels, and internationally lauded restaurants, gangs fight for turf in the area’s rapidly expanding drug trade. The conflict has led to 900 murders in 2019, more than the annual total for 2018, in a country that already has one of the world’s highest murder rates. The root cause of the bloodshed lies in the five decades of apartheid social engineering, during which the Cape Flats were starved of funding, quality education, and police resources. Despite 25 years of democracy, that legacy has persisted.

On July 12, the government of President Cyril Ramaphosa said it would call in the army to quell the violence. “The deployment shows that there has been a failure on the part of the police to meet its constitutional mandate: to prevent, investigate, and combat crime,” says Dalli Weyers, head of policy and research at the nongovernmental Social Justice Coalition, which is based in the Cape Town township of Khayelitsha.

Ramaphosa was quick to emphasize that the deployment—which took place on July 18—was a “defense force of democratic South Africa.” But for many South Africans, the presence of troops in the Cape Flats evoked memories of the last years of apartheid, when townships were patrolled by government forces and protests were put down with a heavy hand. Since 1994, the army has only been deployed twice in major cities—Johannesburg, Durban, and Cape Town—to end bouts of xenophobic violence.

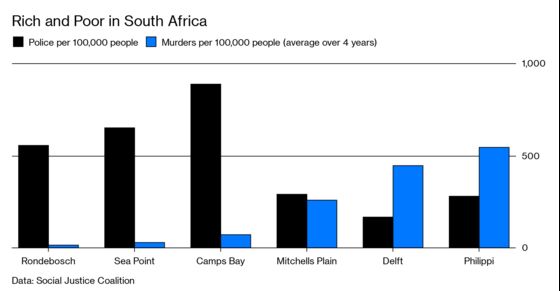

Inequities in policing have remained an issue, however. In December, the Western Cape Equality Court ruled the allocation of police resources in the province discriminates against black and poor people. “There’s really been a woeful underinvestment in neighborhoods like Nyanga, Manenberg, and Khayelitsha,” says Ziyanda Stuurman, an expert on policing strategies and a Fulbright scholar at Brandeis University. “From 2010 we’ve seen a huge rise in gang activity, organized crime, and drug trafficking.”

In Camps Bay, a popular beach strip that’s home to trendy bars and multimillion-dollar luxury apartments, the number of police per 100,000 residents averaged 887 from 2013 to 2017, while the murder rate averaged 72 per 100,000 people. In the Delft neighborhood, located in the Cape Flats, there were 168 police and 445 murders per 100,000 residents over the same time period. A study conducted by the government of Western Cape province in 2017 and 2018 found that 95% of people in the Cape Flats felt unsafe on the street at night. Daylight wasn’t safe, either: Children out playing have been the victims of stray bullets from shootouts.

South Africa has the world’s highest recorded youth unemployment, with 53% of people ages 15 to 24 jobless, according to the International Labour Organization. Cape Town is a conduit city for heroin trafficking—the country is one of three major routes for the drug out of Afghanistan. The trade in South Africa is worth at least $260 million, according to a conservative estimate by Simone Haysom, a senior analyst at the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime. Cape Town is the epicenter of gang activity, which also feeds off protection rackets and trade in other drugs including crystal meth.

Some analysts say the administration of ex-President Jacob Zuma is partly to blame for the spike in gang violence. During his nine-year rule, corruption, some of it linked to the state, rose significantly. “There has been massive and heavy-handed repression of drug users, but no attempt to undermine organized crime’s control of the drug market,” says Haysom. “The criminal justice system needs to reconstitute itself after a period of corrosion of the institutions under the Zuma administration. That’s really the legacy of the last 10 or so years.”

Those years have also been characterized by bickering between the national government of the ruling African National Congress, which controls the police, and the opposition Democratic Alliance party, which runs Cape Town and has regularly been accused of favoring the predominantly white residents of wealthier suburbs.

“I am a thug. What I do, selling drugs and other illegal things, is not good, but what am I supposed to do?” says Pretty Boy, a 46-year-old gangster in the Bonteheuwel neighborhood. He wore sweatpants and a beanie with a pompom as he stood in the street surrounded by younger gang members. “We read in the newspapers that government is spending 23 million rand ($1.7 million) for the army to come here. Why don’t they use that money to improve people’s lives instead?”

Wesgro, the tourism and trade promotion agency of the Western Cape and Cape Town, sees little impact on tourism from drug-related violence. The army deployment is in “specific, isolated areas” and will help increase the safety of tourists in the city, says Tim Harris, the agency’s chief executive officer.

For now, the military deployment is being hailed as a success. Over the weekend of July 19-21, there were 25 murders, compared with 55 over the weekend July 5-7, according to the Western Cape government.

“When you have such blatant gang activity that residents can’t go to work or children can’t even go to school, something is very wrong,” says Stuurman, the policing expert. “The army deployment is a symbolic move. Unless there’s a long-term plan to give the police the resources they need to take this on, you might see the army back again in a few years.” —With Rene Vollgraaff

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jillian Goodman at jgoodman74@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.