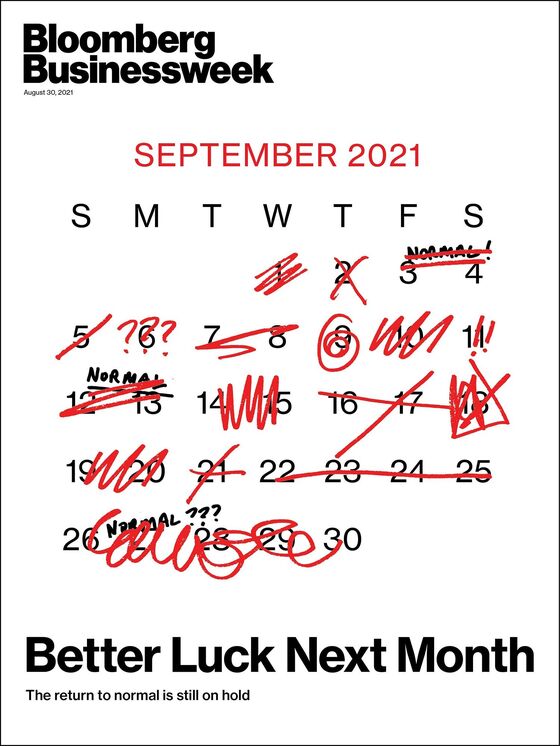

Remember When September Was Going to Be the Return to Normal in the U.S.?

Remember When September Was Going to Be the Return to Normal in the U.S.?

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- When President Joe Biden signed a $1.9 trillion U.S. stimulus package in March, dissolving most of the emergency pandemic safety net come September seemed to make sense. Vaccinations were rising rapidly, and schools were preparing to resume in-person learning in the fall, removing two main hurdles keeping people—especially parents—out of the workforce.

All spring long, that month was heralded as a symbolic turning point for the U.S. economy. With schools set to reopen, companies solidified September return-to-office dates. Virus fears were abating, with the country in May on track to have 75% of the population vaccinated in September. The shortage of workers—brought on by a mismatch between the robust snapback in consumer demand and the number of Americans willing and able to work—was expected to “fade in the coming months and disappear by the fall,” Goldman Sachs Group Inc. economists said in May. It “makes sense” to end the temporary boost in unemployment benefits in September as planned, Biden said in June, and about half the states announced plans to end the expanded jobless aid before the expiration date.

“If you took the data points that were available at that time, theoretically you would’ve said September, and that’s what everyone said,” says Joshua Barocas, associate professor of medicine at the University of Colorado School of Medicine. “There was actually agreement with the two ends of the spectrum that generally are pitted against each other—the economic sector and the public-health sector.”

But the month that originally seemed like a logical time to ease fiscal support is here, and it’s not proving to be the inflection point for normalcy that policymakers and business leaders had imagined. The delta variant of the coronavirus is ripping across a country with far lower vaccination rates than Congress had been modeling when it wrote the latest relief bill. With inoculation rates down from their spring pace, it will still take until almost 2022 to vaccinate 75% of the population, Bloomberg data show.

“If you could do the world where delta never showed up, then September wouldn’t have been so bad for a lot of the fiscal relief to start expiring,” says Claudia Sahm, a senior fellow at the Jain Family Institute and a former Federal Reserve economist. Now though, “there’s a lot of relief that shouldn’t be expiring.”

Several key federal aid programs related to the labor market are set to end on Sept. 6—Labor Day, of all days—including an extra $300 a week in unemployment benefits. Also ending is a program that provides support to those not traditionally eligible, such as self-employed and gig workers. A third provision about to end offers additional weeks of benefits, similar to a program implemented in the 2007-09 recession. Compounding the issue, an eviction moratorium renewed this summer—though also scaled back—is scheduled to end on Oct. 3.

The U.K.’s furlough program, which for more than a year paid 80% of wages for workers who lost their jobs during the pandemic, is also set to expire in September. The delta variant hit there earlier, lessening some of the concerns about returning to work and school, though infections are creeping up again.

In the U.S. the delta variant has already disrupted the back-to-school season, including delayed start dates and the reinstatement of virtual learning, threatening many parents’ return-to-work plans. Within two weeks of opening, a high school in Mississippi temporarily transitioned to virtual learning after 20% of students and staff were either infected or quarantined. Companies such as Alphabet Inc.’s Google and BlackRock Inc. have pushed return-to-office dates to October. Delta has also disrupted already strained supply chains. China temporarily closed a terminal at one of the world’s busiest ports to quarantine dockworkers, delaying shipments of materials that businesses and factories need.

“I viewed September as an inflection point particularly with regard to addressing some of the supply-side problems the economy’s been struggling with,” says Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody’s Analytics. But if schools don’t reopen, it will significantly delay “the ability of parents to get back to work, and for people to get back in their seats, and for the labor supply issues to iron themselves out.”

Delta’s spread is beginning to show up in economic data. The University of Michigan’s Consumer Sentiment Index plunged in early August to its lowest since 2011. Spending on Bank of America cards is moderating, and Southwest Airlines Co. just reported an increase in trip cancellations. On Aug. 18, Goldman economists lowered their growth forecasts for the current quarter, citing a “somewhat larger” than expected impact from the delta variant. The group now expects inflation-adjusted consumer spending to decline in August before bouncing back.

The variant’s emergence has challenged a host of assumptions, including the idea that the pandemic was nearing an end in the U.S. Improved health conditions were expected to help normalize global trading backlogs, revive some overseas travel, and allow the world’s largest economy to refocus some of its efforts on stemming the virus abroad, rather than prioritizing booster shots internally.

The more contagious variant may start to slow its spread, based on what transpired in the U.K. But “if we get into September and infections and hospitalizations are still increasing, then I think forecasts are going to start to change at that point and financial markets are going to react,” says Zandi of Moody’s.

The official indicators illustrating the variant’s impact in August won’t start trickling out until September, when the unemployment insurance extensions expire, says Sahm, the former Fed economist. The jobs report will land on the final workday before the expanded benefits end, and August’s retail sales won’t hit until Sept. 16.

Even if the indicators do signal a contraction in consumer sentiment or spending in August, there’s no provision in the relief bill to extend the programs. Allowing the safety net to expire come September is “much harsher than in recent recessions given the number of continued unemployment claims, the state of the recovery, and ongoing uncertainty due to the spread of the delta variant,” according to Annelies Goger, a fellow at the Brookings Institution, a think tank in Washington, D.C.

Some pandemic-era protections have already been extended, including a pause on student loan payments. The U.S. program previously known as food stamps, which would have seen a temporary benefit boost end on Sept. 30, recently was permanently expanded the most it’s ever been in the program’s history. Still, the Biden administration said in a letter to lawmakers on Aug. 19 that conditions exist in many states to end the supplemental unemployment programs as scheduled. State and local governments can choose to use pandemic-relief funds for added help beyond the deadline. Some states have seen their unemployment rates fall to near or even below pre-pandemic levels, but others—Nevada and California among them—remain extremely elevated.

If it “gets to that point where people are just afraid to go outside their front door, like we were in the beginning of the pandemic, then there’s going to have to be a safety net there for the families that can’t go to work because their industry shut down,” says U.S. Secretary of Labor Marty Walsh.

Progressive think tank the Century Foundation estimates 7.5 million workers will lose all unemployment benefits on Sept. 6 when the main pandemic programs end.

“There are still thousands to millions of households that are behind on their rent payments who have lost significant amounts of income due to the pandemic,” says Carolina Reid, associate professor of city and regional planning at the University of California at Berkeley.

One key deficiency of the U.S. safety net is that it’s largely not tied to circumstances on the ground, says David Wilcox, director of U.S. economic research at Bloomberg Economics and a former Fed economist. “Regardless of what the forecast was at the time that the bill was enacted, the real world wasn’t going to unfold that way,” he says. “For the labor market to heal entirely, a lot of things have to come in place. It’s not enough for just a couple things to fall in place correctly.” —With Katia Dmitrieva, Josh Eidelson, and Benjamin Penn

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.