Rebooting Communist Kicks for Modern Sneakerheads

Rebooting Communist Kicks for Modern Sneakerheads

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- A dozen years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, Alexander Barré noticed a friend sporting shoes he recognized from his childhood in the former East. They were quirky and old-fashioned—and seemed ripe for revival as a brand aimed at urban hipsters. With no experience in the shoe business, Barré sought the advice of an 80-year-old cobbler who’d worked with Puma SE and Adidas AG. “If you had any idea what you’re getting yourself into,” the man told him, “there’s no way you’d do this.”

Barré pressed on with the blend of naive passion and raw excitement all entrepreneurs exhibit when faced with finger-wagging parents, partners, friends, and industry veterans such as the cobbler. Many—even most—end up in financial ruin. Some live to tell the tale of building a business, though typically after countless setbacks. Barré grappled with suppliers who failed to supply, materials of dubious origins, fickle business partners, overexpansion of the store network, and even a burglary at a shop. “We were absolutely clueless,” he says. “For 10 years, every time I opened my mouth I swallowed water, because we were drowning.”

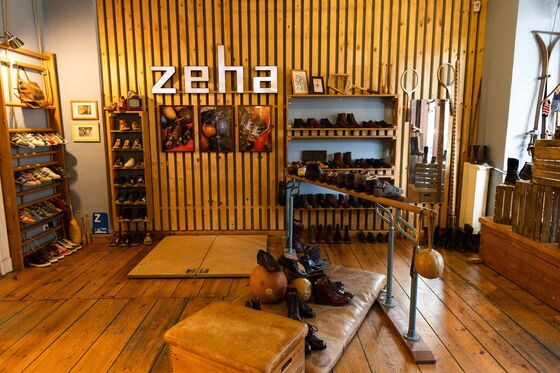

Today, Barré’s Zeha Berlin Schuh Design GmbH brand sells not only sneakers but also dress shoes, socks, bags, and wallets made from scrap leather. Last year, Zeha generated revenue of roughly €3 million ($3.4 million), employed about 20 people, and had a healthy online business that makes up some 40 percent of sales. He’s got a pop-up store in London; is planning to push into Italy, Scandinavia, and possibly Australia; and is working on cycling shoes in collaboration with the organizers of a vintage bike tour.

In East Germany, Zeha was pretty much the only sports shoe available, as the likes of Adidas, Puma, and Nike came from the other side of the Iron Curtain. The company traces its roots to 1897, when a young cobbler named Carl Häßner started making sturdy leather shoes he called Zeha—a riff on the German pronunciation of his initials. After World War II, Zeha’s factory in the small eastern town of Hohenleuben was partly nationalized and began to specialize in athletic shoes for schools, soccer clubs, and even Olympic hopefuls in places as far-flung as Canada, Cuba, and Iceland (which paid in herring). In the 1950s the company changed its logo—four parallel stripes—into two angled double lines when Adidas complained it was too similar to its three-stripe pattern. The state took full control of Zeha in 1972, forcing out the four owners as the Communist Party consolidated its grip on the economy.

After the collapse of communism, East Germans, long deprived of Western wares, had scant interest in owning a pair of Zehas. Demand imploded, the factory closed, and the remaining shoes found their way to vintage shops, flea markets, or the dumpster. But by 2002, when Barré saw his friend wearing a pair, the timing seemed right to bring Zeha back from the grave. Adidas and Puma had successfully reissued classic designs, and Puma had a line of made-in-Italy designer shoes that pushed the boundaries of what’s considered a sneaker. “People love brands with a history,” says Barré, clad in blue and white Zehas and worker jeans.

He discovered that no one had claimed the Zeha name, so he was able to buy the rights for a few hundred euros in administrative fees. He trekked to the derelict factory, interviewed former employees, and dug up old designs. For the first model he settled on a handball shoe with a distinctive rubber toecap and clean lines he thought would work for streetwear. A breakthrough came in 2006 when Germany hosted the soccer World Cup, and Zeha produced a sneaker that looks like a cross between a bowling shoe and a sturdy old-fashioned soccer boot. Called the Carl Häßner, it’s become the company’s best-seller, retailing for €229 a pair.

Although Barré sought to benefit from nostalgia for the brand and a guarantee of German craftsmanship, assembling the shoe in Germany proved impossible because the test models didn’t meet his quality standards. “The soles would literally fall off,” he recalls. “If you go to market with that kind of shoe, you’re toast.” After unsatisfactory attempts at production in Italy and Slovakia, Barré finally settled on Portugal, where Zeha has been making its shoes since 2010.

Barré, one of three owners, says he’s been approached by people eager to invest, which might let him escape the daily grind of running a small business. But he says he wants to keep growing on his own steam rather than selling to someone who might be too ambitious. “There’s interest, particularly from the U.S.,” Barré says. “But I’ve seen new owners push, push, push, and then the brand overstretches and fails.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Eric Gelman at egelman3@bloomberg.net, David Rocks

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.