How Unfair Property Taxes Keep Black Families From Gaining Wealth

How Unfair Property Taxes Keep Black Families From Gaining Wealth

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- It’s the last weekend of the month, so Di Leshea Scott’s Saturday begins with a long wait at the post office to get a money order for her rent. From there, she drives north to hand-deliver it at a drab office building just outside Detroit’s city limits. As always, this ritual leaves her angry and frustrated; her landlord refuses to give her a lease, she says, or to make basic repairs. When it rains, she needs three buckets upstairs to catch leaks. The back porch is collapsing before her eyes.

She stands outside the landlord’s empty office and sighs, then moves a welcome mat aside and flings an envelope with her money order under the door. Another $825 destined for someone else’s bank account.

Despite its flaws, Scott clings to her little two-story Tudor on Lawrence Street with a devotion that’s hard to fathom, until you know the house’s ownership history. She’s renting a home she used to own. Wayne County took it away from her in 2013, after she fell three years behind on her property tax payments. Her house, which she’d bought in 2005 for $63,800, was auctioned off by the county and snapped up by an investment company for less than $5,000. Scott lost every cent she’d put into it.

She shouldn’t have. For years the city of Detroit used inflated valuations of Scott’s house to calculate her property tax bills, charging her thousands of dollars more, cumulatively, than she should have paid, according to a Bloomberg Businessweek analysis of her tax records. Hers was among tens of thousands of homes in Detroit’s lower-income Black neighborhoods that the city’s assessors routinely overvalued. Meanwhile they systematically undervalued homes in affluent areas, reducing the taxes those homeowners paid.

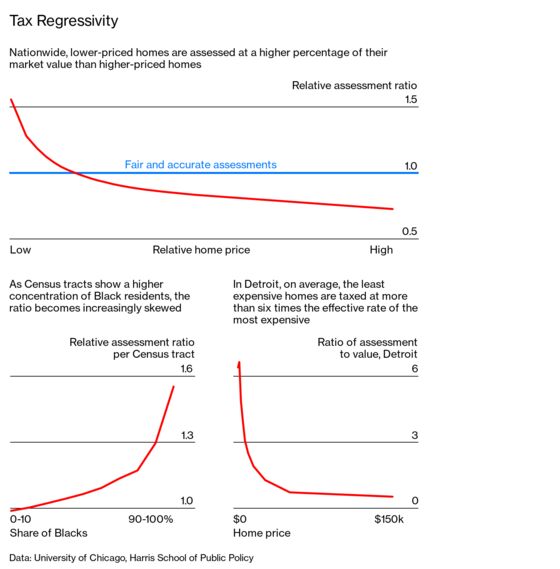

It’s not just Detroit. Local officials have overvalued the lowest-priced homes relative to the highest across the U.S., nationwide data show. From 2006 through 2016, inaccurate valuations gave the least expensive homes in St. Louis an effective tax rate almost four times higher than the most expensive. In Baltimore it was more than two times higher. In New York City it was three times higher.

These inequities are tucked deep inside America’s system for funding its local governments, tilting property taxes in favor of wealthy homeowners even before any exemptions or abatements. And they carry a jarring implication: The residential property tax, which raises more than $500 billion annually to pay for public schools, fire departments, and other local services, is, in effect, racist.

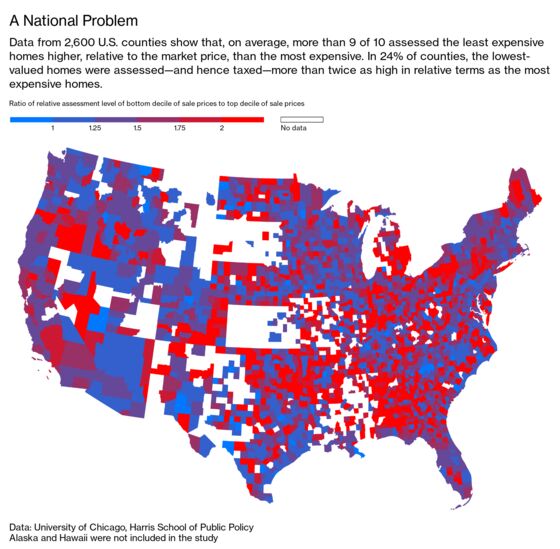

That conclusion carries far-reaching implications of its own—not only for municipalities’ day-to-day operations but also for roughly $331 billion in general-obligation bonds that cities, counties, and school districts have guaranteed with property tax revenue, according to data compiled by Bloomberg Businessweek. The evidence of systematic unfairness is mounting. Since at least the 1970s, piecemeal studies from Chicago, Detroit, New Orleans, and New York have concluded that property tax systems favor those who are better off. A 2020 study from the University of Chicago brings unprecedented scope to the question, covering 2,600 U.S. counties. It found that more than 9 out of every 10 reflected the same pattern of unfairness. “It’s a textbook example of institutional racism,” says Christopher Berry, a professor at the university’s Harris School of Public Policy who led the research effort.

The problem is rooted in American history. One legacy of racial discrimination, including the practice of redlining (the refusal of banks to make loans in Black communities), is that Black people own a disproportionate share of lower-valued real estate. Census data show that the median home value in predominantly Black tracts is roughly half the value in majority White and Hispanic tracts. That historical disparity has been aggravated by a flawed tax system built on incomplete data and outdated methods for estimating the value of residential properties. “There isn’t anybody making explicitly racial decisions to produce these outcomes,” Berry says. “Nevertheless, they are racially disproportionate.”

Wide variations in policies and rates among the many thousands of U.S. jurisdictions that levy property taxes make it difficult to quantify the aggregate size of the imbalances. But Berry found in 2018 that in Chicago alone, unfair assessments shifted $2.2 billion in property tax payments from those who owned the highest-valued homes to those who owned the lowest-valued homes—over only five years.

Unfairness doesn’t end there. While tax assessments tend to overvalue many Black homeowners’ property, private appraisals done for the purpose of securing mortgage approvals consistently undervalue them. The president of the Appraisal Institute, a professional organization, this year called it “an absolute priority” to work on addressing such issues, which experts say help widen the wealth gap between Black and White households.

In extreme cases, such as Scott’s, unfair tax burdens lead to unpaid bills and property seizures, destroying the best chance for families to build generational wealth. Meanwhile real estate and bond investors reap windfalls from a money machine that floods local markets with foreclosed homes and securitizes the tax debts into bonds with generous yields.

Scott says she began saving for a house while working in a corporate cafeteria for $6 an hour. Her income doubled when she got a job at a domestic-violence shelter, and during the mid-2000s housing bubble she qualified for a mortgage. Owning a home gave her three children the kind of stability she’d never known herself, and the house became home base for her family and friends. Her best friend helped scrub soot off the foyer’s marble tile. Her sister hung curtains in the living room. “For me, it’s not just a piece of property,” Scott says. “It’s where life has existed.”

Then, in 2011, she lost her job during the Great Recession and missed her annual tax payment, for $3,120.

Property tax bills are generally calculated based on two factors: the tax rate and the assessed value. The tax rate is straightforward; the same percentage will apply to every piece of residential property within the local taxing district. The assessed value is where things get funky. And even if you think your assessment is fair, you really can’t know that until you see how yours compares with everybody else’s.

A few years ago, Carmen Daniels, a retired public school assistant principal in New York, thought she was getting a decent deal. The city valued her home in East New York, Brooklyn, purchased for $93,000 in 1998, at $380,000 for the 2014-15 tax year—close to the market price, she figured, considering the brisk appreciation of New York real estate. Then, last year, she learned that a doctor in Clinton Hill, less than three miles away, had been taxed for the same period as if his home were worth only $1.2 million, less than half the $3 million he’d recently paid for it. That low valuation combined with additional quirks in the doctor’s case to set his tax bill only one-third higher than hers, though his place was worth eight times as much.

“It’s such a crock of nonsense,” says Daniels, who’s among a group of homeowners working with the community organization East Brooklyn Congregations to pressure New York politicians to fix the system. “It’s just the same set of racial injustices continuing.”

It’s no easy task to assign values to every home in a given city or county. Most assessments are based on recent sales, and because the vast majority of homes won’t have sold recently, assessors have to use data from those that did sell to estimate values for all. That process, known as mass appraisal, relies on computer models that calculate the average value of individual attributes—such as square footage of living space, number of bathrooms, and location—for the homes that have sold. Assessors then apply the resulting averages to the attributes found at each residence.

By definition the use of average values means that higher-priced homes will be undervalued and low-priced homes will be overvalued. More important, assessors are barred from entering houses without permission, so they have no real data on their relative quality, including individual improvements or maintenance issues that might affect value. Even if they could survey every home, most assessment offices lack the resources to do so. Such information gaps will prevent even the best assessors from fully eliminating inequities, Berry says.

It’s generally accepted that affluent homeowners are less likely to put off repairs, making high-priced housing stock more uniform and therefore easier to value. Experts say assessed values at the low end of the scale tend to vary more, adding difficulty that contributes to inflated assessments.

Alan Dornfest, an assessment expert in Idaho, doesn’t dispute the pervasive imbalances that Berry found, but he blames policies set by local governments, not the technical limitations of mass appraisals. For example, some jurisdictions impose caps that limit how much any home’s taxable value can increase in a year, distorting valuations. Studies have shown that the complex cap system in New York has benefited owners of high-priced homes disproportionately. “Assessors, however well-intentioned and professional, often are shackled by those policies,” Dornfest says.

Regardless of the causes, the effects can be devastating. Consider Scott’s history in Detroit: Six months after she bought her house in 2005 for $63,800, the city valued it at $72,292. By 2008 the housing market had begun to collapse, and Detroit’s housing prices were down more than 25%, according to the S&P CoreLogic Case-Shiller Index, which tracks home prices in major U.S. cities. Yet, because assessments often lag large market swings, the city’s market valuation of Scott’s home rose over that time, to $76,268. From 2005 to 2011, the city charged her at least $5,800 more than she would have paid if the assessment had been pegged to the market. That’s 80% more than the missed payment that triggered her foreclosure.

By 2013, Scott owed back taxes of almost $10,000, and her misfortune was fueling a money machine that benefited real estate firms, bond investors, and even, in the end, her local government. After foreclosing on her home that year, Wayne County officials used Scott’s delinquent property taxes, and those of thousands of other people, to back $267 million in municipal bonds. Even though Wayne County’s credit rating was among the worst in the U.S., investors bought up these delinquent tax anticipation notes, or DTANs, secure in the knowledge that their repayment was all but assured: The bond covenants spelled out that the county could seize the parcels on which the taxes were owed and sell them off. In the end, even the county itself got the benefit of a little arbitrage: Between fines, late fees, and proceeds from auctions, it pocketed $73 million more than it had to pay out in debt service that year. Since 2005 the county has issued more than $3.3 billion in DTANs.

The year after the county foreclosed on Scott’s home, a Utah company that buys low-priced rental housing picked it up at auction for $4,607. It sold the place roughly five years later for $32,500.

The house’s market value kept rising, partly because the landlords kept increasing Scott’s rent. But in a perverse twist, the city’s tax assessments on the house began falling. In February 2020, when a Michigan company bought the house for $84,000, its taxable value was listed at only $24,600. Scott says she now pays more to rent her home than she paid on her old mortgage, about $650.

Detroit officials have acknowledged overtaxing about 130,000 city residents from 2010 to 2013. That happens to be the period before Mike Duggan became mayor, in 2014, and ordered a reassessment of every residential property in the city.

Last November, Duggan proposed a resolution that would have admitted to the historical unfair taxes while setting aside $6 million to offer affected homeowners first dibs on affordable housing or half-price deals on vacant city land. His measure was expected to pass. Instead the city council voted it down after a contentious virtual meeting. Housing advocates and angry homeowners testified that the proposed remedy was inadequate, and they cited research that showed the city’s property taxes remained deeply unfair—even worse than before the reassessment. That research was part of the nationwide effort by Berry and his team of graduate students at the University of Chicago.

Experts evaluate property tax fairness with a straightforward process that’s based on actual sales. For each home that sold in a year, they calculate a ratio that puts the assessor’s estimated market value over the actual sale price. If the ratio equals 1, the assessor nailed the valuation. A ratio greater than 1 signals an overvalued property; less than 1, undervalued.

A full-on sales ratio study looks for patterns across all recent sales. Berry’s study found the same pattern repeatedly: overvaluations linked to lower sales prices, and undervaluations linked to higher sales prices. This is classic regressivity, an overburdening of those least able to pay.

It’s true that various factors can influence sale prices—some sellers are more motivated, some buyers more choosy. The International Association of Assessing Officers, which writes assessment standards, has suggested that any perceived regressivity in ratio studies such as Berry’s could result from that sort of “random noise” in prices. While the group didn’t answer detailed questions about Berry’s study, it cautioned that “ratio studies, like all statistics, are only tests. They can never confirm the presence of regressivity, only suggest it.” Still, the University of Chicago study found so much regressivity, in a dataset that was so large, the problem has to be systemic, Berry says. Seven economists and law professors who reviewed Berry’s findings told Bloomberg Businessweek they warrant major policy discussions and further research.

In Detroit, whose property tax system Berry identified as one of the most inaccurate in the U.S., city officials haven’t exactly embraced the findings. They’ve accused him of being a right-wing provocateur who’s shilling for low taxes. They’ve disputed his ability to judge the city’s work from Chicago. They’ve argued that his analysis was too broad; it compared fairness across all of Detroit’s neighborhoods, whereas Michigan law carves cities into smaller geographical areas for gauging assessors’ work. (Even within those smaller units, Berry’s analysis found the same inequities.) They implied he lacked an appreciation of creative approaches to valuation. “Valuation is an art, not a science,” says Alvin Horhn, Detroit’s assessor. “You have to know the neighborhoods. You have to know why people are making their decisions. You have to know the quality of the properties in those neighborhoods. It’s not just looking at numbers on a spreadsheet.”

This isn’t the first time Berry has been sucked into local politics. In 2017 I wrote a series of articles for the Chicago Tribune that showed Cook County’s residential property tax system was deeply unfair. During the reporting I took my findings to Berry, because years earlier he’d helped the county develop a model intended to reduce regressivity. My findings suggested that the county had never implemented his model.

Berry was incredulous at first. After all, Cook County officials had issued a press release claiming to have used his model to achieve more fairness. But he soon realized that his model had been ignored, and he spoke out about it. In response, Cook County officials attacked him personally. They claimed he was seeking to make money off the new model, even though the county owned the rights to it. They denied that the system, which they’d hired him to improve, had ever been unfair. It was only after an independent review corroborated the inequities that the county acknowledged them.

The Cook County experience motivated Berry to begin his national study. “I had been thinking of this as an only-in-Chicago sort of phenomenon,” he says. “But as that Chicago work began to get attention, I started to hear from people elsewhere. And every place I look, I’m finding something similar. The names change, and some of the details are different. But the overall pattern of inequity is repeated, place after place.”

Di Leshea Scott still hopes to buy back her house, more than six years after losing it. She’s saving as much as she can. In addition to her full-time job at the domestic violence shelter, she’s delivering food on nights and weekends, often to the suburbs and more affluent areas of Detroit—“to these fancy homes, and they are all lit up and beautiful.”

She longs to have something to leave her children. “I have to have a plan for them,” Scott says. “I can’t just say, ‘OK, this is it. See you guys later.’ ” But she says she hasn’t had the heart to tell them that she no longer owns the home they grew up in.

Read next: Southern Bancorp Is Bringing Equality to Banking With Loans for the Underserved

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.