The Billion-Dollar High-Speed Internet Scam

The Billion-Dollar High-Speed Internet Scam

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- When he discovered that the ship’s underwater plow was stuck at the bottom of the Arctic Ocean, 50 miles off Alaska’s coast, Frank Cuccio thought of Ernest Shackleton. In October 1915, the British explorer was forced to make a desperate escape from the Antarctic after pack ice and floes crushed his ship, the Endurance. The vessel Cuccio was aboard, the Ile de Batz, had been laying fiber-optic cable along the inhospitable route known as the Northwest Passage. But the Ile de Batz’s 55-ton excavator, which had been cutting a trench for the cable, had dug too deep in the hard-clay seabed. If they didn’t unclench it fast, the ocean surrounding them would soon freeze. “I realized we don’t have time to fool around, or we’re going to get trapped in a Shackleton situation,” Cuccio recalls. “The weather was getting uglier, and other ships had been gone for weeks.”

Cuccio worked for Quintillion Subsea Holdings LLC, a telecommunications startup in Anchorage that was trying to build a trans-Arctic data cable it said would improve web speeds for much of the planet. This idea captivated the public, but by the time the Ile de Batz’s plow got stuck, in September 2017, the company was struggling. Co-founder Elizabeth Pierce had resigned as chief executive officer a couple months earlier amid allegations of fraud.

Pierce had raised more than $270 million from investors, who had been impressed by her ability to rack up major telecom-services contracts. The problem was that the other people whose names were on those deals didn’t remember agreeing to pay so much—or, in some cases, agreeing to anything at all. An internal investigation and subsequent federal court case would eventually reveal forged signatures on contracts worth more than $1 billion. In a statement about the controversy, a Quintillion spokesman says, “The alleged actions of Ms. Pierce are not aligned with how Quintillion conducts business. Quintillion has been cooperating fully with the authorities.” Pierce, through her lawyer, declined to comment.

The company resolved the Ile de Batz crisis, coordinating with Cuccio and dozens of partner engineers and divers to hoist the plow from the depths. But it’s unclear whether Quintillion’s business will find momentum again. Last week, Pierce began serving a five-year prison sentence after pleading guilty to one count of wire fraud and eight counts of aggravated identity theft. The U.S. Department of Justice has said it believes nearly all the investment capital she secured was acquired fraudulently. The company is trying to repair its reputation while planning the extension of its internet pipeline from Asia to Europe. “I don’t care what Elizabeth’s original plan was,” says George Tronsrue, the company’s interim CEO. “Short of the headlines she grabbed with her bad behavior, she’s irrelevant to Quintillion’s future.”

Much of Pierce’s behavior, though, wasn’t so different from that of other tech founders and CEOs promising financiers vast rewards right over the horizon. A Bloomberg Businessweek review of hundreds of pages of court documents, as well as interviews with three dozen people familiar with Pierce’s Quintillion fraud, suggest that her ability to conjure up a Shackleton-esque vision of achieving the impossible proved as captivating as her forged signatures. “Elizabeth was so committed to making Quintillion successful that she just dreamt all this shit up,” says a former company executive, who, like many sources, spoke on the condition of anonymity for fear of retaliation. “The question is not why Elizabeth did it, but rather, how did she think she’d get away with it?”

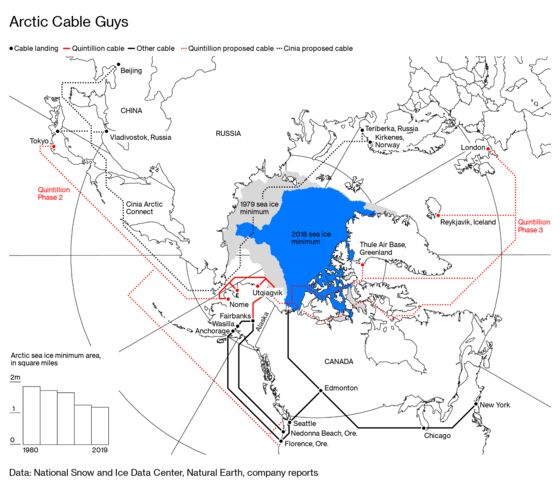

Arctic fiber has been an entrepreneurial fantasy for decades. Soaring demand for broadband helped drive companies, including Google, Facebook, and Amazon.com, to spend tons on high-speed underwater cables that keep customers watching Netflix and YouTube with minimal delay. But many of those lines run in parallel in the Atlantic and Pacific along well-established ocean routes, leaving the world’s internet vulnerable to earthquakes, sabotage, and other disasters both natural and human-made. A trans-Arctic route would help protect against that while offering a more direct path, potentially making internet speeds much faster.

From Quintillion’s inception in 2012, Pierce focused her ambitions on her home state of Alaska. The state’s satellite internet was slow and expensive. In the lower 48, connections approaching 1 gigabit per second hover around $70 a month. Rural Alaska customers could pay double that for dial-up speeds. “If you wanted to watch Game of Thrones, you’d be better off getting a friend to record it on a CD and mail it,” says Quintillion engineer Daniel Kerschbaum.

In theory, this meant a big opportunity, particularly as climate change warmed open more paths for construction in the Arctic. Pierce and her co-founders, who all had experience working at Alaskan telecom companies, figured they could develop faster, fiber-based broadband and then sell it wholesale to local internet service providers. The team spent most of 2013 conducting research, assessing environmental concerns, and negotiating cable routes with indigenous tribes. Even without completing any intercontinental routes, wiring Alaska for fiber would end up requiring 14 ships and 275 government permits and rights-of-way authorizations. “The dream of a Northwest Passage makes sense on paper,” says Tim Stronge, vice president of research at the consulting company TeleGeography. “But it’s so hard to get funding.”

After Pierce met Canadian father-son entrepreneur duo Doug and Mike Cunningham, who were pursuing a similar network with their startup, Arctic Fibre Inc. (AFI), they decided to form a partnership. The Cunninghams said they could raise $640 million, and committed to overseeing the international portion of the 9,500-mile cable that would run from Japan to England. Quintillion would be responsible for Alaska, arguably the most difficult segment.

Pierce, with her blonde bangs and Quintillion-branded puffer vests, looked like a friendly-yet-stern camp counselor. People close to the former CEO say she could be aggressive in business dealings, perhaps a result of her years working with Alaska labor unions on contract negotiations in the 1990s.

This style—my way or the Dalton Highway—extended outside the company, too. In 2014, Quintillion filed a defamation lawsuit against a telecom lobbyist in Juneau for allegedly calling the business a “big scam” in an email to a customer. At an industry conference, one attendee recalls making a joke to friends that Arctic cables felt as sci-fi as a Jules Verne novel. After she heard the comparison, Pierce confronted this attendee. “I’d never even met Elizabeth,” this person says. “My comment was so trivial, but she was really angry and defensive. She seemed under a great deal of stress.”

No major venture capital firms invested in the Quintillion-AFI project prior to 2015, according to court documents. The market of teeny Arctic communities didn’t seem to justify the huge upfront expense, one reason why Alaska rivals mostly used satellites and microwave antennas, rather than fiber lines, to reach low-population centers in a state more than twice the size of Texas.

At a crossroads, the Cunninghams proposed a merger. Pierce agreed but ultimately orchestrated an acquisition of AFI’s assets and cut the Cunninghams out of management, according to people familiar with the matter. She was willing to peddle promises grander than what she could deliver, these people say. At a meeting with investment bank Oppenheimer & Co., a relationship Pierce took over from the Cunninghams to seek financing, an Oppenheimer analyst predicted that Quintillion could squeeze only $30 million in annual contracts from its Alaskan cable. Pierce pounded the table and promised $75 million a year, says a person present at the meeting. “Whenever you challenged Elizabeth, she’d double down,” the person says. An Oppenheimer spokeswoman declined to comment.

Oppenheimer set up talks with Cooper Investment Partners, or CIP, a private equity firm in New York founded by Stephen Cooper, the CEO of Warner Music Group. Leonard Blavatnik, a Soviet-born oil magnate who owns WMG, is CIP’s largest shareholder through a variety of holding companies, according to an FCC filing. At an introductory meeting, CIP representatives said the firm would invest only if Pierce could show them completed contracts that guaranteed a certain amount of revenue upfront. Although Quintillion had previously struggled to close such deals, Pierce convinced CIP managing director Adam Murphy she could do it, and by early 2015, the firm invested $10 million. (Blavatnik and Cooper declined to comment. Murphy declined interview requests and did not respond to a detailed list of questions by email. In a statement, he says, “We are focused on the future, not the past.”)

Pierce’s solution wasn’t complex. It was “so rudimentary,” she later submitted in court, that it’s shocking nobody caught the grift sooner.

Pierce scribbled her first forged signatures on contracts with the Matanuska Telephone Association, which services south-central Alaskan towns such as Wasilla, in May and June 2015. Although Matanuska CEO Greg Berberich had been reluctant to strike a deal, Pierce assured her investors in New York in an email that Berberich was “nervous but very committed.” The next day she uploaded a contract, worth hundreds of millions of dollars, with what looked like Berberich’s signature to a personal Google Drive account she shared with Murphy, the CIP managing director. Pierce also said she was close to locking in another gigantic sale with the nonprofit Arctic Slope Telephone Association Cooperative, whose customers include residents of remote Inupiat communities and the city of Utqiagvik. Soon she sent Murphy a contract with a phony version of the Arctic Slope CEO’s signature, too.

Pierce executed similar deceptions at least eight times, and the fraudulent contracts totaled more than $1 billion, according to court filings. Sometimes she completely fabricated deals; other times she negotiated real contracts, then changed key pages with more favorable terms. Quintillion’s other 10 or so employees were kept at arm’s length. “I am the only person at Quintillion to authorize or otherwise accommodate customer requests or alleged contract issues,” she wrote in an email to a customer. She solely controlled the password to her Google Drive and stored printed contracts in a private filing cabinet, which she once scolded a subordinate for opening, according to a former employee. On a team conference call with Murphy, this person remembers Pierce kicking a Quintillion executive under the table to stop his report of new accounting data.

Murphy, who became more involved with the business as Pierce’s apparent sales streak continued, spent time in Alaska meeting customers, several sources say. When he inquired about a $600 million contract that Pierce said she’d struck with another Alaskan telecom, Pierce admitted negotiations had soured but said she had more contracts coming that would offset the lost revenue. Over time, Pierce raised $270 million from CIP and French investment bank Natixis SA. “There were signs things were screwy,” says a Quintillion backer. “You wanted to believe in the good she was doing. How many people were putting together billion-dollar projects in Alaska?” A Natixis spokeswoman declined to comment.

This perception contributed to an aurora-like glow around Pierce, whose earnest-sounding pitch for closing the digital divide in Alaska made her a star of telecom conferences. In August 2016, Governor Bill Walker joined her at a media event in the Aleutian Islands. Federal Communications Commission member Ajit Pai, who has since become the FCC’s chairman, even flew to Alaska to tour Utqiagvik, where he met Pierce and later appointed her chair of an advisory committee on rural broadband. Pai declined to comment.

Still, the mounting pressures began to take a toll on Quintillion’s CEO. Friends assumed Pierce’s severe respiratory issues, which they say led to repeated cases of flu and other illnesses, were a result of the stresses of 14-hour days and frequent travel. Later they’d attribute these problems to crippling anxiety, which seemed to keep her forever on the brink of a crash.

During this time, Pierce’s income averaged at least $146,000 per year in salary and other benefits, according to public records. She and her husband, William, lived in a four-bedroom home. On the side, they ran a construction business out of a garage-turned-office near Quintillion’s Anchorage headquarters. Quintillion operated in the former garage, too, before moving into a brick building that could double as a rural post office, recall three people familiar with the matter. Elizabeth’s assistant sat in a hallway near Bill’s truck.

Unusual financing supported the family’s lifestyle. In 2013, Pierce mentioned an opportunity to invest in Quintillion to an old work acquaintance, Julian Jensen, who thought the project was “strategically viable.” In May that year, according to court documents, he wrote her the first of three checks totaling $325,000, a third of his savings.

Pierce deposited the initial check, for $100,000, into her personal bank account, court documents indicate. That same day, these documents show, she established her own retirement plan at Wells Fargo & Co. and transferred $30,500 into the account. She also used Jensen’s funds to pay off her and Bill’s credit-card bills and mortgage, cover household expenses, and invest $10,000 into their construction business. At one point, she cut their son a $500 check, jotting “just because” in the memo line. Pierce did allocate a portion of Jensen’s capital to Quintillion: Prosecutors later claimed she “loaned” $43,300 to the company and spent $28,000 to acquire shares in her own name. By the end, there was $49 left in her Wells Fargo account. (At her trial, Pierce denied opening a retirement account with Jensen’s investments, which she said she mostly used for Quintillion.)

In 2015, Pierce found another source of income after a Quintillion worker and former coffee shop barista, Erica Blair, inquired about investing. (Blair’s real name was redacted in court filings. She spoke to Bloomberg Businessweek on the condition that she be identified only by a pseudonym.) Pierce told her that if she could come up with $40,000, that would earn her 225 Quintillion shares. Blair cobbled together the cash from family, hoping it would turn into a nest egg for her kin. Pierce deposited those funds into her Wells Fargo account, according to court documents.

The following year, Quintillion kicked off construction of its subsea cable network, partnering with Alcatel Submarine Networks Ltd. But the seabed was stiffer than expected, and weather conditions quickly worsened. Pierce had to cease operations and delay the project a year.

The costly setback made investors skittish. But whenever Jensen and Blair would ask for shareholder documentation, Pierce convinced them their investments were solid. She provided Jensen a spreadsheet showing his shares had gained in value. Murphy and the CIP team also pressed for greater insight into Quintillion’s customer contacts, but Pierce insisted that Alaskans simply didn’t trust outsiders and that it would be better for her to keep managing everything alone.

In early 2017, a Quintillion employee prepared to send out invoices for Quintillion’s supposed megadeals, but Pierce came up with reasons to pause the process, likely to keep her forgeries from being discovered. Matanuska Telephone, she said, might break its purchase obligations for internet capacity on their land cable. According to court documents, Pierce advised CIP to avoid litigation because it might jeopardize a larger sales agreement she claimed to have struck with Matanuska for underwater cable usage. She vowed to supplement the disappearing revenue and continued to repeat this process as a similar pattern played out with another customer.

By mid-2017, Pierce had run out of excuses to delay sending out invoices. She could no longer hide her scheme after customers, who were still unaware she had entered them into massive revenue commitments, saw their bills. Berberich, who had retired two years earlier as Matanuska’s CEO, said the hundreds of millions of dollars he didn’t remember committing to Quintillion would bankrupt his old company. (A Matanuska spokesman says it has taken the necessary steps to safeguard its stakeholders.) Lawyers for Quintillion’s customers disputed the invoices, and one telecom contacted CIP. Disconcerted, a CIP employee logged into the Google account Pierce shared. Yet all the contract files were now missing. Two days earlier, on July 14, the Google log read, “Elizabeth Pierce moved 78 items to the trash.”

A week later, a CIP lawyer questioned Pierce. Pierce, who brought her own personal lawyer, said she was unable to recall the circumstances of every contract signature. After 30 minutes she stopped and left the interview, saying the inquiries felt so out of the blue. They rescheduled for the next day. But hours before that meeting, her attorney canceled and, the following day, submitted Pierce’s resignation.

Murphy scrambled to find a successor, especially because Quintillion had ships going back to work near Alaska to complete the fiber-optic network. CIP recruited George Tronsrue, a seasoned telecom executive and Army veteran, who joined in early August. Tronsrue focused on Quintillion’s operations aboard the Ile de Batz, where, over the course of 15 days the following month, Alcatel Submarine Networks repaired the 55-ton plow and finished the subsea cable as ice sheets bumped their boats. Meanwhile, Quintillion says, it reported Pierce’s actions to federal authorities in late September.

Throughout 2017, Pierce behaved as if nothing were awry. She held a ribbon-cutting in April with Alaska Senator Lisa Murkowski at a cable-landing site in the oil town of Deadhorse and calmly delivered keynotes at conferences into the summer, months after her scams had been uncovered. “Elizabeth is a dreamer, an innovator, and a person who just likes to get things done,” said the host at a May event at the University of Alaska at Fairbanks. A grinning Pierce quipped, “Obviously, I didn’t write that bio.”

In early 2018, she met with Blair, the former Quintillion worker who invested $40,000. Over coffee they chitchatted about family. Pierce said she’d left Quintillion to spend more time at home. But, she said, there might be a problem honoring Blair’s shares in Quintillion. (In truth, the shares didn’t exist.) There was good news, though: She had decided to make Blair a beneficiary on her life insurance. “Why would you do that?” Blair asked, confused. Pierce responded cryptically: “You never know what can happen.”

In April 2018, the Department of Justice announced Pierce’s arrest. Shortly after, public records indicate, her family sold her Anchorage residence for $415,000 and purchased a home in Texas near Austin, which was put in Bill’s name. (Prosecutors argued this was an attempt to shield assets from forfeiture. Bill Pierce couldn’t be reached for comment.) Near the time of her arrest, Pierce phoned a longtime friend who was oblivious of her misdeeds, but the call went to voicemail. “ ‘Things are about to get crazy—we’ll talk later,’ ” she said, according to this friend. “That’s the last time I ever heard from her.”

On a freezing May afternoon, Tronsrue and Kerschbaum, the Quintillion engineer, are smashing along in a white van on the icy outskirts of Utqiagvik, the northernmost community in the U.S. Kerschbaum steers through ashen snowdrifts, and 20 minutes outside town, we stop at a nexus of Quintillion’s network, demarcated by posts poking out of snowbanks.

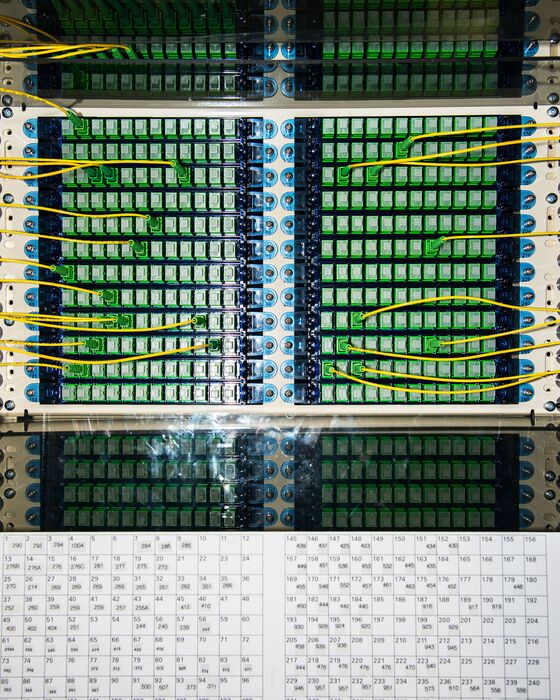

To link the subsea cable to its land fiber, Quintillion had to drill a mile-long channel 80 feet underground, from the ocean to this snow-buried manhole, and splice the cables. At a nearby cable-landing station, they show me the wires where data enters and exits through its underwater and terrestrial cables to Alaska customers.

Tronsrue, who has silvery hair and a Jeff Bridges drawl, tells me he spent months after the unraveling of Pierce’s scandal salvaging Quintillion’s relationships with customers. He was able to recover some agreements; others fell apart. In a sign of progress, Jens Laipenieks, CEO of Arctic Slope Telephone, joins us at the cable station to praise Quintillion. “We were at dial-up speeds years ago, but now our subscribers can do things like stream Netflix, play Xbox online, and process Square payments,” he says.

Ultimately, Alaska got its subsea cable network, stretching around the tips of its coast. Quintillion estimates it’s connecting some 10,000 residents to a usable contemporary internet, in addition to local schools, hospitals, and other business customers. Crawford Patkotak, a whaleboat captain and chairman of the Arctic Slope Regional Corporation, a native-owned business group and a minority shareholder in Quintillion, similarly credits the cable company with bringing Utqiagvik into the digital age. “There’s even ocean service now,” he says over reindeer Bolognese at the Top of the World Hotel restaurant. “My friend gets mad at his crew: ‘Get off your damn phone! We’re out here whaling!’ ”

Later we drive past the kinds of places that Tronsrue says represents the future of Quintillion’s business, including Cold War-era military installations and fields sprinkled with mammoth satellite dishes. He says the company is considering building a data center and also sees potential in government contracts.

During my Alaska visit, Quintillion execs never mention Pierce, but that doesn’t stop her name from coming up. At Utqiagvik’s Arctic Research Center, which many government agencies use for climate-change studies, our guide grumbles that the internet hasn’t improved. “We were promised all this stuff by that lady, Elizabeth,” he says. At the town’s Ilisaġvik College, Chief Operating Officer Brian Plessinger complains to Tronsrue that, since switching to Quintillion fiber, the new service “hasn’t made a difference. We pay $9,500 per month for just 10 megabits, but with 2,000 students, it slows to a halt.”

Immediately after, Tronsrue is on his phone figuring out if there’s a way to help Plessinger. It turns out that the college’s bandwidth had improved over its old internet connection, while its cost per megabit fell roughly 70%. But there’s no doubt the service had not lived up to what Pierce pledged. In the ensuing months, Tronsrue worked to quintuple the college’s speed at no extra cost. “Nothing changes overnight,” Tronsrue says. “You either adapt or you get kicked in the teeth.”

It’s unclear whether Quintillion will complete its loftier goal of constructing an Asia-to-Europe internet cable via the Northwest Passage. Tronsrue insists that objective hasn’t changed, though he acknowledges it will take $800 million to fund. Meanwhile, the Matanuska Telephone Association recently announced a cable from the North Pole to the contiguous U.S., and a Finnish company is developing its own $600 million Arctic fiber. Pierce appears to have proved there’s potential in this market, even if her vision of a Northwest Passage for the internet remains a dream.

On Sept. 30, after more than a year of court proceedings, Pierce surrendered to a federal penitentiary in Texas. Prosecutors from the Southern District of New York, which handled the case because Quintillion’s majority investor CIP is based in Manhattan, argued that she acted alone. They claimed Pierce placed her “ruthless ambition and greed” above the law. Yet the judge expressed confusion. Given Pierce’s successful career and lack of criminal history, he said, the former CEO’s motivations remained a “mystery.”

During her sentencing, Pierce and her lawyer said she didn’t gain much personally from the scam and otherwise spent CIP’s funds on Quintillion. “I am financially, professionally, and socially ruined,” Pierce said in a plea to the judge to reduce her jail time. She stressed she’s not an “evil manipulator.”

It’s true that CIP didn’t lose everything. Court documents indicate that while Quintillion’s telecom contracts will generate $480 million less than what Pierce projected, annual earnings could reach their promised 2018 numbers by 2023.

Other Quintillion backers weren’t so fortunate. Blair has struggled to make up with her family over her lost $40,000 investment. “I was devastated, crushed—to this day, it’s still mind-numbing what Elizabeth did,” Blair says. “Alaska really needed this system, and I worked really hard for Elizabeth.”

And yet, Pierce somehow still has fans. Desiree Pfeffer was Quintillion’s chief business relations officer and says she is now a board member. She was close with Pierce—never catching a whiff of her duplicity, she swears—and mostly remembers the ex-CEO for her tenacity. “This is going to sound weird. Elizabeth gave everything to this project,” Pfeffer says. “I got burned like everyone, but frankly, I would work with her again.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jeff Muskus at jmuskus@bloomberg.net, Max Chafkin

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.