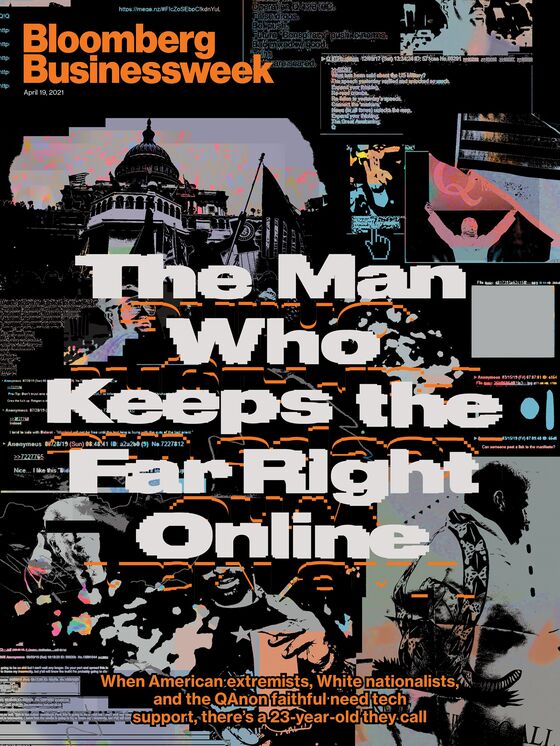

A 23-Year-Old Coder Kept QAnon Online When No One Else Would

A 23-Year-Old Coder Kept QAnon Online When No One Else Would

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Two and a half months before extremists invaded the U.S. Capitol, the far-right wing of the internet suffered a brief collapse. All at once, in the final weeks of the country’s presidential campaign, a handful of prominent sites catering to White supremacists and adherents of the QAnon conspiracy movement stopped functioning. To many of the forums’ most devoted participants, the outage seemed to prove the American political struggle was approaching its apocalyptic endgame. “Dems are making a concerted move across all platforms,” read one characteristic tweet. “The burning of the land foreshadows a massive imperial strike back in the next few days.”

In fact, there’d been no conspiracy to take down the sites; they’d crashed because of a technical glitch with VanwaTech, a tiny company in Vancouver, Wash., that they rely on for various kinds of network infrastructure. They went back online with a simple server reset about an hour later, after the proprietor, 23-year-old Nick Lim, woke up from a nap at his mom’s condo.

Lim founded VanwaTech in late 2019. He hosts some websites directly and provides others with technical services including protection against certain cyberattacks; his annual revenue, he says, is in the hundreds of thousands of dollars. Although small, the operation serves clients including the Daily Stormer, one of America’s most notorious online destinations for overt neo-Nazis, and 8kun, the message board at the center of the QAnon movement, whose adherents were heavily involved in the violence at the Capitol on Jan. 6.

Lim exists in a singularly odd corner of the business world. He says he’s not an extremist, just an entrepreneur with a maximalist view of free speech. “There needs to be a me, right?” he says, while eating pho at a Vietnamese restaurant near his headquarters. “Once you get to the point where you look at whether content is safe or unsafe, as soon as you do that, you’ve opened a can of worms.” At best, his apolitical framing comes across as naive; at worst, as preposterous gaslighting. In interviews with Bloomberg Businessweek early in 2020, Lim said he didn’t really know what QAnon was and had no opinion about Donald Trump.

What’s undeniable is the niche Lim is filling. His blip of a company is providing essential tech support for the kinds of violence-prone hate groups and conspiracists that tend to get banned by mainstream providers such as Amazon Web Services.

It’s almost impossible to run a real website without the support of invisible services such as web hosting, domain name registration, and protection against distributed denial of service (DDoS) attacks, which involve crashing a site by bombarding it with junk traffic. Getting banned by AWS, Cloudflare, or other infrastructure providers, as the Daily Stormer and 8kun have been, is a step beyond a ban from Facebook or Twitter. It puts the American far right on a short list that includes child pornographers and terrorist organizations such as Islamic State—groups that promote and incite violence and basically aren’t allowed to have websites. “Every time I see an article attacking social media companies—and they deserve it—I think it’s more important to go after the companies that are hosting terrorist material,” says Rita Katz, founder of SITE Intelligence Group, a nonprofit that tracks terrorist activity online. “There’s already a good recipe that was used for ISIS. Why don’t you use it on the far right?”

It’s tougher to keep a site such as the Daily Stormer offline as long as somebody like Lim is willing to support it. U.S. laws governing domestic extremism are less expansive than those focused on international terrorism, partly to protect the rights of U.S. citizens with unpopular political views. And even the big web-hosting companies have struggled to set consistent standards. While Cloudflare has refused to work with the Daily Stormer, it supports other sites peddling racism, including those for Stormfront and the Committee for Open Debate on the Holocaust. The overlap between Republican Party officials and the belief systems that sparked the Capitol attack, which started out as a Trump rally, can make it all the tougher to draw clear lines.

Voices from across the U.S. political spectrum have registered concerns about companies setting up litmus tests to ban groups from the internet. That said, the voices Lim supports tend to come from the same general neighborhood. He sought out Andrew Anglin, who runs the Daily Stormer, to offer the neo-Nazi free tech support. He says his largest customer is 8kun, and he has a personal relationship with Ron Watkins, the site’s former administrator and one of its key leaders since its inception.

Lim argues that the real political crisis facing the U.S. is not extremist violence but erosion of the First Amendment. He says that restrictions on online speech have already brought the U.S. to the verge of communist tyranny, that “we are one foot away from 1984.” After a moment, though, he offers a sizable qualifier: “I never actually read the book, so I don’t know all the themes of the book. But I have heard the concepts, and I’ve seen some things, and I thought, ‘Whoa! That’s sketchy as f---.’ ”

VanwaTech’s headquarters is a squat, one-story house in a sidewalkless subdivision that’s just over the state line from Portland, Ore. Lim inherited the place from his grandparents, according to state records. While he regularly talks about VanwaTech as a growing enterprise with a dedicated staff, he seems to be the only one around who’s working at the company. He rents rooms on the cheap to friends from high school who help keep the party going. The crew has nicknamed the house Vansterdam.

When Lim greets visitors, the front door swings open to a view of a coffee table covered in cold McDonald’s fries and a collection of half-smoked joints. The backyard is littered with weightlifting equipment and bongs, along with a shed full of computer servers for mining cryptocurrencies.

Lim attributes his entrepreneurial streak to a need to “put food on the table” during an underprivileged childhood, even though classmates remember him driving other kids around in his dad’s Lamborghini and posting videos of the rides to YouTube. High school peers say Lim was obsessed with ostentatious displays of wealth and talked constantly about Bitcoin and The Wolf of Wall Street, the movie starring Leonardo DiCaprio as a much more glamorous version of con man Jordan Belfort.

When he’s not doing wheelies on his bicycle, Lim now gets around in an Audi A6 with a Harvard Law School license plate holder, which he calls a gag. (He didn’t go to Harvard, or to law school.)

One of his early forays into entrepreneurship was OrcaTech, a service for website owners to test how well they could withstand DDoS attacks, essentially by launching simulated attacks at them. For a certain kind of customer, the tool could also help execute attacks on others. Lim says that he never looked into whether it was used for malicious purposes, but he adds that protecting against abuse is almost impossible, comparing himself to a locksmith who can’t be sure customers are bringing him their own keys. He eventually shut down the operation out of concern that he’d be implicated in illegal activities.

Lim says he “got famous” after reaching out to Anglin. He’d read about the difficulties the Daily Stormer was having staying online. He wrote to Anglin on Gab, a social network popular among the rightist fringe, and offered free use of BitMitigate, his latest DDoS protection product. When asked why he wanted to do business with one of the U.S.’s most notorious White supremacists, Lim shrugs: “They were censored, so that’s what was interesting about them.”

He then launches into a rambling justification, questioning whether the Daily Stormer is actually serious about the racism that defines it. “They could be joking,” he says. Either way, he adds, “I just don’t care. To me, it’s not illegal speech.”

If it’s working right, infrastructure should be invisible. As with sewers and electrical grids, sturdy domain name servers and distributed hosting services allow the people who rely on them to focus on more pressing matters. It’s possible to run websites in the face of hostility from the huge companies that host most sites and protect them from attack. But it’s not easy, and the sites that do it tend not to work that well.

The Daily Stormer’s infrastructure troubles really began shortly after White supremacists rioted in Charlottesville, Va., in 2017. After the riot, Anglin posted an article mocking Heather Heyer—the counterprotester murdered by a neo-Nazi in attendance with his car—and a handful of tech companies pulled the support the site needed to stay online. This started with GoDaddy Inc., which had provided its domain name registration, the service that links the location of content on a server to a URL someone can type into a web browser. Cloudflare, which had protected the Daily Stormer against DDoS attacks, also banned it, as did a handful of other service providers. The site began bouncing around between permissive, offshore hosting providers, leading to periodic service outages and a general deterioration of its usability.

Over the past few years, several other sites have been similarly hobbled or taken offline after their users were implicated in racist massacres. In 2018, Gab went offline after a mass murder at a synagogue in Pittsburgh by a person who kept a profile marked by anti-Semitism on the social network. The people who ran Gab denied they were running an extremist website, describing theirs as an open forum for anyone seeking a less censorious alternative to Facebook. When Gab lost its domain name registration, a Seattle-based company named Epik made a show of taking it on.

At that point, Epik had spent years in the mundane business of nonideological domain registration, and Rob Monster, its awkwardly named chief executive officer, had a reputation for personally handling customer service calls and posting on arcane industry forums. But Monster had also been radicalized during the Trump years, subjecting his staff to florid conspiracy theories in staff meetings and spending more and more of his energy on politically charged work at Epik.

Around this time, Lim and Monster began collaborating. It’s not clear how they met, but they quickly grew close, with Monster becoming a kind of mentor to Lim, according to Joseph Peterson, then Epik’s director of operations. In 2019, the company bought BitMitigate, the Lim service that was supporting the Daily Stormer. As part of the deal, Lim became Epik’s chief technical officer.

By the time Lim arrived, Monster’s political fixation had come to dominate Epik, says Peterson, who describes himself as progressive. Peterson says he agreed with Monster’s view that domain registrars shouldn’t refuse clients based on their political views. He likens the business to the hospitality industry, arguing that a hotel shouldn’t kick out otherwise untroublesome guests whom the proprietor overhears saying racist things. It’s a different matter, he says, when a registrar becomes a beacon for racists urging violence. The blowback that followed Epik’s support of Gab led Monster to prioritize working with extremist sites such as Alex Jones’s InfoWars.com, according to Peterson. “Once a hotel invites the neo-Nazis, hosting their convention year after year, that’s no longer ethical,” he says. “That’s where I feared Epik was going.”

Rob Davis, Epik’s senior vice president for strategy and communications, said in an email that Peterson was biased and that the idea Epik would pursue extremist clients was “categorically nuts.” He said Epik cut ties with BitMitigate’s previous clients, including the Daily Stormer, and had no direct contact with Anglin.

Peterson says he quit the company soon after Monster began a staff meeting by telling attendees to watch a video of the 2019 mosque shootings in Christchurch, New Zealand. He says the CEO claimed the video would convince his employees that the massacre had been faked.

Before killing 51 people, the perpetrator of the New Zealand massacre had posted a manifesto to 8chan, the precursor to 8kun. That August, another young man followed the same pattern, crediting the site for radicalizing him before a mass murder in El Paso. “I’ve only been lurking here for a year and a half, yet, what I’ve learned here is priceless,” the shooter wrote of 8chan before killing 23 people. In the wake of the shooting, Epik declined to support the site, citing “inadequate enforcement and the elevated possibility of violent radicalization on the platform.”

About the same time, Lim left Epik and announced he had started VanwaTech. The new service would prove critical to getting 8kun online and keeping it there. Lim was central enough to the effort that he flew to Japan to celebrate the site’s launch with Jim and Ron Watkins, the site’s owner and administrator, who are father and son. On Election Day, Ron announced that he’d stepped down as 8kun’s administrator. He was later banned from Twitter for promoting election-related conspiracy theories.

In October, Bloomberg Businessweek emailed Monster, requesting an interview to discuss Epik’s political philosophy and its relationship with Lim. Davis, the Epik executive, sent a nine-page response arguing that Epik had been demonized unfairly and had done a great job of combating extremism. Davis accused the news media of trying to destroy the lives of Epik employees and said the interview request itself was part of an attempt to manipulate the 2020 presidential election. “The long and short of it,” he wrote, “is that we don’t give interviews to traitors of our country that participate in attempted coups sponsored by offshore money.” He cc’d close to 100 other recipients, including the Republican chair of the Federal Communications Commission, the antitrust division of the Federal Trade Commission, and Fox News host Sean Hannity.

In response to follow-up questions about Lim’s connection to Epik, Davis wrote that Lim was just a short-term consultant. He described the line of questioning as a ploy to “cover the tracks of pedophiles and smash small businesses.”

Along with the vagaries of Lim’s napping schedule, the sites relying on VanwaTech might have to worry about its proprietor’s conflicts with the likes of SITE Intelligence; Fredrick Brennan, 8chan’s repentant founder, who occasionally sparred with Lim online; and Ron Guilmette, an internet researcher and activist.

For more than a decade, Guilmette has dedicated most of his time to chasing spammers and people who sell phony vitamins around the internet. He’s developed a deep knowledge of the architecture of the web, and his tactics include pressuring his targets’ tech-support partners to stop working with them. The Californian, whose political views are a hodgepodge of mostly liberal ideas, says he chased bad actors because he thought they were crooks, not for ideological reasons—until this summer, when he found himself increasingly agitated by QAnon’s influence on U.S. politics. Guilmette decided to try to take down 8kun. “I set myself the task of causing as much trouble as possible for this one particular website,” he says.

Guilmette decided the best way to get to 8kun was Lim. In October, he persuaded CNServers, the Oregon company that guarded VanwaTech’s 254 internet protocol addresses against DDoS attacks, to cut it off. When CNServers did so, 8kun went offline for about an hour before VanwaTech switched to another service provider. He now uses DDoS Guard, a Russian company less sensitive to pressure campaigns.

Web hosting for 8kun has since been spread over 11 IP addresses held by three different companies, all based in Moscow and in business with DDoS Guard, says Guilmette. Scattering the site across numerous servers appears to be a tactic designed to make it harder to take offline. “I feel like I’ve been chasing them, like the foxes and the hound,” Guilmette says, adding that the Daily Stormer and 8kun are being “kept alive and breathing on the internet only because Mr. Nick Lim is keeping them.”

The politics of web hosting rose to national prominence after the insurrection at the Capitol. Parler, which has replaced Gab as the buzziest right-wing social network, went offline after Amazon deprived it access to AWS. It stayed down for a month, increasing the conviction among many conservatives that the companies who run the internet are aligned against them. The site came back online in February and has been mostly stable since then.

Lim sees the rising concerns around high-tech censorship as a business opportunity. He had nothing to do with getting Parler back online, but the incident aggravated distrust in large tech companies in a way that could work to his benefit. He says he’s been furiously buying extra racks of computers on EBay to keep up with the increased business. Over the course of several conversations, Lim also repeatedly suggests he’s going to focus more on hosting pornographic websites, which aren’t exactly digital pariahs like some of his other clients but are controversial enough to face hostility from some service providers. “A lot of people will say, ‘Oh, that’s an abuse of free speech to post nude pictures,’” he says. “Some people won’t service a nude website. We don’t care.”

Read next: Facebook Built the Perfect Platform for Covid Vaccine Conspiracies

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.