Putin Sticks to ‘Russia First’ Even as Workforce Shrinks

Putin Sticks to ‘Russia First’ Even as Workforce Shrinks

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Vladimir Putin is taking a page from Donald Trump’s tough-on-immigration playbook. That’s bad for people like Umed and the millions of migrants from other former Soviet republics who have flocked to Russia in search of work. The 29-year-old Tajikistan native, who declined to give his full name, had been working as a delivery driver in Russia when he was deported in 2015. “They don’t want Muslims to live in the country,” says Umed, who now resides in Kazakhstan.

Immigrants are Russia’s best hope to replenish a 75-million-strong workforce that’s shrinking by 800,000 people a year. Yet their numbers are barely growing as Putin’s government has tightened regulations, largely in an attempt to curb the influx from Central Asia. This is a major headache for Russian companies, many of which are struggling to fill jobs even though the economy is stagnant.

“Business needs the extra manpower, but the authorities are desperate to avoid provoking voter anger,” says Alexei Makarkin, deputy director of the Center for Political Technologies, a Moscow-based research organization. “Times are hard, and that’s bolstering anti-immigrant sentiment.”

Just two years ago, Putin boasted at his annual end-of-year press conference that his government had managed to reverse the demographic slump triggered by the collapse of the Soviet Union. But in last month’s state-of-the-nation speech he warned of a fresh population crisis. “We have entered a very difficult demographic period,” he said, unveiling a series of new benefits for families to encourage them to have more children. “Russia’s future, her historical prospects, depend on how many of us there are.”

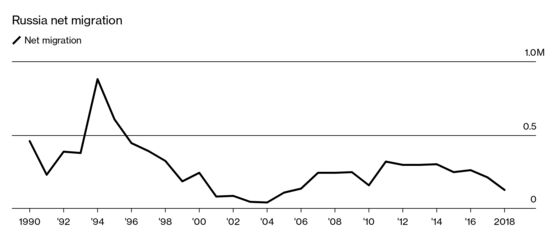

In 2018, as the flow of migrants fell to its lowest point in 13 years, Russia’s population recorded its first dip since 2008—a decline that continued last year. By 2050, according to Russian and United Nations forecasts, the nation will have 10 million fewer inhabitants than its current 146 million.

As part of Putin’s campaign to raise life expectancy to 80 years by 2030, Russia has made huge strides in tackling the causes of its high death rate. Sales restrictions slashed alcohol consumption by 43% from 2003 to 2016, while excise taxes and other measures have driven down tobacco use by more than 20% in just seven years. The measures have raised life expectancy to more than 73 years, from a low of 65 soon after Putin came to power.

The government has had less success in boosting the birthrate, which plunged to 1.2 births per woman at one point in the 1990s, which is why the country now suffers a shortage of women of childbearing age. At 1.5 births per woman, Russia’s fertility rate is now comparable to that of Western European nations, but remains below the so-called replacement rate needed to keep the population stable.

“Migration should be the top priority,” says Anatoly Vishnevsky, director of the Institute of Demography at the Higher School of Economics in Moscow. Yet the foreign-born population is barely growing: It was 12 million in 2019 (equal to 8% of the total), the same as in 2000, according to United Nations estimates. In the U.S. the foreign-born population rose from 35 million to 51 million over the same period.

The demographic situation could be “turned around if the authorities didn’t worry about a backlash,” Vishnevsky says. In an interview with the Financial Times last year, Putin slammed German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s decision to admit more than a million refugees in 2015, mostly from war-torn Syria, as a “cardinal mistake.” He also said he understood Trump’s campaign pledge to build a wall between Mexico and the U.S. The influx of migrants from Central Asia provokes “irritation among the local population” because of cultural differences, Putin said at a press conference in December.

During a meeting with human-rights activists in 2013, Putin bluntly stated his views on what kind of migrants he would like to see. Svetlana Gannushkina, a leading campaigner for immigrant rights, says Putin told her in a private exchange that Russia needs “people of Slavic appearance, of reproductive age, and with a good education.” That describes the people leaving, not those coming to Russia, says Gannushkina. Up to 2 million Russians have emigrated since 2000, according to a study released last year by the Washington-based Atlantic Council.

The government has tried to lure the 30 million native Russian speakers living outside the country’s borders with incentives that include fast-track citizenship approvals. Yet despite an influx of Ukrainians fleeing the conflict in 2014 between pro-Russian separatists and the Kiev government, less than a million so-called compatriots have accepted Moscow’s invitation of resettlement in the past dozen years. That number doesn’t include 227,000 inhabitants of eastern Ukraine who took up an offer of Russian citizenship in 2019 but may not actually move to Russia.

Vyacheslav Postavnin, a former deputy head of the Federal Migration Service, says the government should be doing more to ensure migrants from non-Slavic cultures integrate successfully. But nothing has been done despite a mass outbreak of nationalist riots targeting Muslim immigrants in Moscow six years ago. “Migrants still live in a parallel universe,” he says.

While nationals from Central Asia make up the bulk of migrant workers in Russia, strict controls block most from acquiring citizenship or even residency papers—and the rules have been tightening for the past five years. Regulations introduced in 2015 require those applying for long-term work permits to pass a Russian-language exam and obtain medical insurance. Fees for temporary working papers can total about 5,000 rubles ($80) per month.

Russia’s largest internet company, Yandex, whose food delivery service employs many migrants as couriers, is resorting to automation to cope with a shortage of prospective hires. It’s rolling out a suitcase-size robot that will be able to take orders to apartment building entrances.

The share of migrants in the workforce of X5 Retail Group, the biggest Russian grocery store chain, has dropped to 40% of the previous total in the past two years, the company says. Its rival Magnit is plastering flyers around apartment blocks and putting ads in local newspapers in hopes of luring stay-at-home mothers and students to take part-time shifts.

Shukhrat Yusupov, a Tajik taxi driver in Moscow who doesn’t have long-term residency papers even though he’s lived here since 1995, confronted the precarious nature of his life in Russia when three teenagers knifed him in mid-2018 outside his apartment building. The assailants were part of a group targeting non-ethnic Russians. Yusupov, 41, who has four children, spent two months in the hospital and only avoided potentially life-threatening injuries because passersby intervened. “They shouted, ‘Go back to where you came from,’ ” he says. “I had to move apartments for our safety. That’s how I live—for now.” —With Naubet Bisenov, Ilya Arkhipov, Stepan Kravchenko, and Zoya Shilova

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Craig Gordon at cgordon39@bloomberg.net, Cristina Lindblad

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.