Putin’s Health-Care Cuts Spark Protests in Russian Heartland

Putin’s Health-Care Cuts Spark Protests in Russian Heartland

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Passengers on the sleek German-made trains racing through the Russian countryside between Moscow and St. Petersburg at 229 kilometers (137 miles) an hour can taste the high life. On the dining car’s menu is a half-bottle of French Champagne and a scoop of black caviar for 10,600 rubles ($163).

They probably don’t take much notice of Okulovka, just over halfway into the four-hour journey. It’s a town in Novgorod, a region where more than a third of people don’t have running water—and glaring economic disparities are hardly new in Russia. But pockets of disquiet rarely seen in the Vladimir Putin era are now putting Okulovka and similarly depressed towns in the Russian hinterland on the political radar.

The catalyst, familiar in countries from the U.S. to the U.K. and even Sweden, is health care. Doctors and other hospital staff in the region have been leading protests over the president’s broken promises of better pay and the threat of clinics closing. They’re being supported by a fledgling trade union backed by a leading Kremlin critic.

Nationwide support for Putin is stable after falling dramatically last year. His approval rating is above 60 percent, and to many in Novgorod he can still do no wrong. Concern, though, that traditionally loyal sections of the population are turning against the authorities raised an alarm in the government, two people close to the presidential administration say.

Protests used to be confined to the big cities. Now they’re in the Putin heartlands, often barren places where promises of a better life ring increasingly hollow. Federal statistics released in March showed that more than a third of Russians can’t afford to buy two pairs of shoes a year.

“We have everything in Russia—natural wealth, an educated population,” says Dmitry Sokolov, a 48-year-old activist who’s playing a key role in mobilizing disgruntled medical staff in the Novgorod region. “The problem is with our leadership—it’s rotten. And people are getting fed up.”

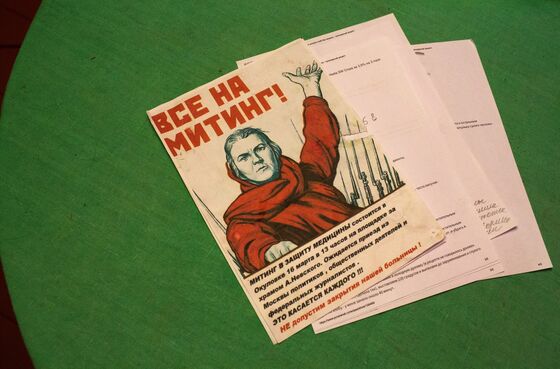

In Okulovka, a town of 10,000, about 500 people turned out for a March 16 rally denouncing the authorities’ policy of “optimizing” medical services, which is prompting cutbacks and suppressing wages for doctors and nurses. On a recent visit, payslips from an ambulance worker and nurse showed monthly income of as low as 10,000 rubles. While the protest in subzero temperatures lasted two hours, a concert held at the same time in the town’s House of Culture to commemorate the five-year anniversary of the annexation of Ukraine’s Crimea peninsula attracted a mere handful.

Yury Korovin, 60, is the only surgeon left in Okulovka hospital, where services are under threat as the authorities focus on medical care in the larger town of Borovichi. Until last year there were four surgeons, but three quit, including two in March who left for better pay in the neighboring Leningrad region.

“I come in and ask the nurse, ‘What medicines have we got?’ She says, ‘Nothing!’ ” Korovin said on April 5 in a hotel room in Okulovka where activists gather. “Patients have to bring their own sheets.” Late last year, because there’s no functioning endoscopic equipment, Korovin had to cut open a patient to stop bleeding in his stomach.

Okulovka wasn’t an isolated event. In January, 200 people protested over cuts to health services in Shimsk, a town of 3,500 also in the Novgorod region. In Saratov, a city in southwestern Russia, residents held a rally in February against the closing of a children’s hospital. Plans to ship Moscow’s trash to neighboring regions have also incited demonstrations.

Apart from Okulovka, the current focus of Sokolov’s work as an activist is a clinic at risk of shutting down in a small locality called Moshenskoye, almost 90 kilometers on dangerously potholed roads from Okulovka. Sokolov, who earns his living selling heating stoves, says his communications have been monitored by the authorities. On a visit to the clinic last month, a district health authority security official was waiting to prevent him from entering.

On March 1, the clinic’s 24-hour service ended, meaning patients could no longer stay overnight. It’s now open from 8:30 a.m. to 5 p.m. That’s left residents in Moshenskoye having to turn to Borovichi, the regional hub 50 kilometers away, in an emergency, says Elena Serebryakova. The 43-year-old is an electricity company employee who joined Sokolov in efforts to enlist medical workers in Moshenskoye into the “Alliance of Doctors.”

Public transport is sporadic. There’s only one bus a day between the two locations. And there’s just one ambulance left in Moshenskoye, covering an area with 6,500 inhabitants. There used to be four, according to the alliance.

The losers are people like Valentin Fetodov, a 71-year-old who suffers from a rare skin disease. He must now spend 1,600 rubles of his 12,000-ruble monthly pension on taxi fares every time he has to visit a specialist in Veliky Novgorod, the region’s capital. Pulling up his trouser leg to show red and crusty skin, he says he also has to pay for his own medicine. Asked if he thought the protests could change things, he says: “There’s no point. I don’t believe in anything anymore.”

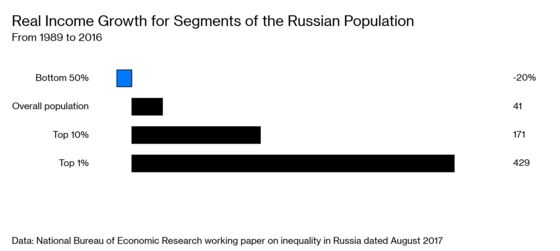

Russia is a country with 100 billionaires, and yet 13 percent of the population lives below the poverty line according to national standards, or twice that based on international norms. For all its military muscle and status as the world’s top energy exporter, Russia’s economy is still smaller than Italy’s or Canada’s.

Putin pledged to halve the poverty rate in the next six years when he campaigned for a second presidential term last year. But the Kremlin’s focus now is on salting away billions in oil profits for fear of new Western sanctions, so little is making its way to ordinary citizens. It doesn’t help that annual gross domestic product growth has barely topped 2 percent since 2013.

“For 15 years people’s incomes were rising, and now for five years things have been going in the opposite direction,” says Denis Volkov, an analyst at the independent Levada polling agency in Moscow. “Their life is getting worse, and they have no hope for the future. Are we going to end up like Venezuela? No. But more and more people are complaining.”

According to the Public Opinion Foundation, voting intentions for Putin fell to 45 percent by mid-2018, from 74 percent in 2015, and have remained at broadly the same level since. His term expires in 2024.

Novgorod’s governor, Andrei Nikitin, is part of a new crop of loyal Putin technocrats sent to the regions by the Kremlin to improve services and blunt discontent. He said the region’s problems with health care have been chronic.

“We understand this problem and we know it can’t be resolved without balancing the medical system’s budgets,” Nikitin said by telephone on May 7. “That’s what we are doing. It means we’re obligated to adopt not the most popular measures. But the final goal is to make medicine as accessible as possible.”

Russia spends about 3 percent of GDP on health, a third of the level of western European nations, and expenditure has been falling in inflation-adjusted terms over the last six years. In March, though, Nikitin announced 2 billion rubles of funding to upgrade a hospital in Valdai, the area in Novgorod where Putin and his associates have properties.

Meanwhile in Moshenskoye, pensioner Galina Emilianova said the quality of health care has steadily worsened. Her 73-year-old sister-in-law was operated on last September for appendicitis, but within a few days surgeons had to cut her open again, and recently once more for the third time in six months.

Emilianova, 65, who lives with her ailing husband in a municipal apartment, has no hot water, gas, or sewage connection. To get access to the mains for cold water a few years ago, she says, she had to take out a 30,000-ruble loan, equivalent to two months’ pension.

“The authorities don’t care,” she says. “They can go to elite hospitals, they have money and cars. They can go anywhere they want. Where can we ordinary people go?” Still, Emilianova doesn’t blame Putin for her predicament. “I like the president, of course. I voted for him. He just has bad people working for him, he can’t keep tabs on all of them.”

Opposition leader Alexey Navalny is hoping to gain political capital with his campaign to highlight Putin’s failed promises in 2012 to raise 8 million medical workers’ and teachers’ pay by 2018 in line with a formula linked to average regional incomes.

He’s teamed up with the Alliance of Doctors trade union, led by Anastasia Vasilieva, a Moscow ophthalmologist, which since last August has set up more than 20 regional branches. Some 10,000 people across Russia have registered online with Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Fund to ask for their case to be raised—most of them anonymously—with the authorities.

Fear is the main problem, according to Vasilieva. At a visit by local activist Sokolov to the Okulovka hospital, security arrived within 15 minutes and called the police. “The authorities are trying to stamp this out,” she says. “Medical workers are afraid they’ll fire them and take away their last means of subsistence.”

But more people are overcoming their apprehension. In December, when the hospital in Okulovka announced it was eliminating one of the three ambulance crews, Sokolov says he collected 400 signatures for a petition opposing the decision in less than a day.

Medical staff who belong to the union have been protesting on and off by working to rule, an alternative to strike action involving following contracts and hours to the letter.

Oleg Andrianov, 68, a former policeman and firefighter who’s been writing protest letters over the health-care cuts, supports the action. Underneath a political poster of a smiling young family dressed in traditional peasant costumes in a wheat field are the words: “United Russia Together with the President,” referring to the ruling party.

“United Russia Together with the President—against the people,” Andrianov says, pointing to it. “That’s how it really is.”

--With assistance from Gregory White.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Cristina Lindblad at mlindblad1@bloomberg.net, Rodney Jefferson

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.