Curt Schilling’s $150 Million Fail Shows What’s Broken in Video Games

Curt Schilling’s $150 Million Fail Shows What’s Broken in Video Games

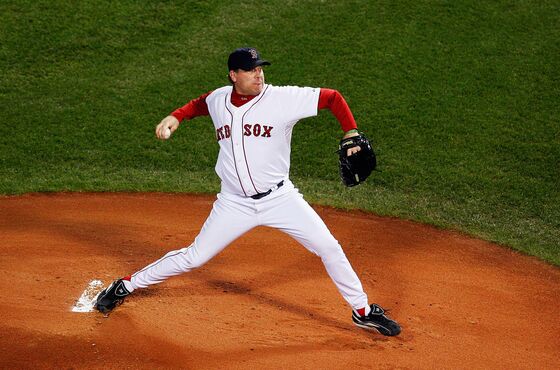

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- 38 Studios was the type of company a teenager might dream up when fantasizing about what it’d be like to make video games for a living. The company was building a wildly ambitious game to compete with the megahit World of Warcraft and appeared to be flush with cash. Employees received top-notch health benefits, gym memberships, and personalized high-end gaming laptops worth thousands of dollars. There were free meals, lavish travel expenses, and Timbuk2 bags customized with an illustration of the world map for their in-progress video game, code-named Copernicus. The man behind 38 Studios was Curt Schilling, the retired pitcher best known for his time with the Boston Red Sox. Schilling was a legend, famous for his performance on the field and his combativeness off it. In the 2004 playoffs, he’d pitched two games with an ankle that had been injured so badly it soaked his sock in blood. The performance helped the team win its first World Series in almost a century, and Schilling’s bloody socks earned a place in baseball lore.

During his playing career, Schilling had been a star, and he thought the people building Copernicus should be stars, too, says Thom Ang, an artist who’d done work for Disney on The Lion King and Toy Story, along with stints at big-name games companies such as Sony, Electronic Arts, and THQ. “He said, ‘That’s how I want my team to feel. I’m going to attract the best, and I’m going to treat them as if they’re the best.’ And he did.”

Ang was skeptical when he first got a call from a 38 Studios recruiter in 2008. But the role-playing game looked fantastic, and the company offered him a hefty relocation package, so he moved from Southern California to become its art director. Sure, the studio hadn’t made a lot of progress in the two years it had been operating, and its timeline to finish the game by the fall of 2011 did seem a little unrealistic, but Ang didn’t think that was a problem. He’d seen how slowly things could move at the beginning of a project. And Ang knew he didn’t have to worry about 38 Studios’ finances or wonder where the money was coming from. After all, Schilling had earned in excess of $114 million over his two decades in baseball.

Video games are big business, generating more than $150 billion in annual sales. The biggest hits account for a disproportionate amount of that revenue, which is why Schilling had said publicly he thought he could get “Bill Gates rich” by building his own blockbuster. But volatility is also the status quo in gaming. Too many companies struggle to provide stable, healthy environments for their workers. All it takes is one flop or sloppy business decision to lead a billion-dollar game publisher to enact a mass layoff or shut down a studio, no matter how much money it made in a given year.

In 2017 the nonprofit International Game Developers Association asked approximately 1,000 game workers how many employers they’d had in the previous five years. Among those who worked full time, the average was 2.2 employers; for freelancers it was 3.6. James Batchelor, a reporter at GamesIndustry.biz, counted up all the jobs lost to studio closures in the 12 months ended September 2018—a time when the industry was thriving—and found the number was over 1,000.

Job listings for big game publishers like Take-Two Interactive Software Inc. and EA advertise careers, not temporary gigs. But there’s actually a high level of instability. Developers who accept the pleasure of creating art for a living must also acknowledge that it might all fall apart without much notice. “With all the layoffs I’ve dealt with, I get a PTSD-type thing whenever there is an email for an all-hands meeting in an office,” says Sean McLaughlin, an artist who has worked in gaming since 2006. “I no longer put more things on my desk than I can carry out in one bag.”

Ang and others at 38 Studios thought this company would be different, and they were right in one sense. Video game studios collapse all the time, but rarely with the kind of star power and political controversy that surrounded its demise.

Schilling first grew obsessed with video games—especially massive multiplayer online role-playing games, where players interact freely in sprawling digital worlds—during long summers on the road as a pro athlete. As his playing career wound down, he decided he wanted to make a video game of his own. He started a company, named it after his jersey number, and seeded it with $5 million. He declared he was going to create a “utopian” office—a place where making video games felt not like a dreary nine-to-five job but like you’d just made it to the big leagues.

This account is based on interviews with former executives and employees at 38 Studios. Schilling initially agreed to an interview but then stopped responding to requests. He had never run a business before, and that became clear with everything he said or did. Early on, he had suggested that everyone work the odd schedules common for professional baseball players, coming into the office for 14 straight days and then taking five days off—an idea that his executives quickly shot down. By the beginning of 2010, he had invested $30 million of his own money into 38 Studios, and although he’d taken other small investments from friends, he knew that 38 needed far more money to bring Copernicus to reality.

Schilling was, in addition to being a serious gamer, a World War II buff, maintaining a collection of historic memorabilia including, most controversially, Nazi uniforms. That March, he met Donald Carcieri, the Republican governor of Rhode Island, at a fundraiser the former pitcher was holding for a documentary on the war he hoped to support. The two started talking about 38 Studios, and the talks eventually developed into a plan for the Rhode Island Economic Development Corp. to create what they called the Job Creation Guaranty Program. Rhode Island would offer a $75 million loan guarantee to 38 Studios in exchange for a commitment from Schilling to relocate from Massachusetts and create 450 new jobs over three years.

For 38 Studios’ employees, the move to Rhode Island represented a potential hardship, so Schilling and his management team offered to pay for home closing costs. More remarkably, they said that anyone who owned a house in Massachusetts and couldn’t sell it would have the option to sell it to 38 Studios, which would take care of mortgage payments until a buyer came along. In the wake of the 2008 housing crash, Ang had a mortgage that was worth more than the value of his house. The deal with 38 Studios seemed like the perfect opportunity to get out of a bad spot.

The company expanded rapidly after the move, in no small part because the loan agreement had stipulated that 38 Studios create the first 125 new jobs in Rhode Island within 12 months of closing. The new employees settled in for the long haul. “The people were top-notch, top talent in the industry,” says Pete Paquette, an animator who joined the company in 2011. “And I was prepared to just live there the rest of my life, to work there the rest of my career.”

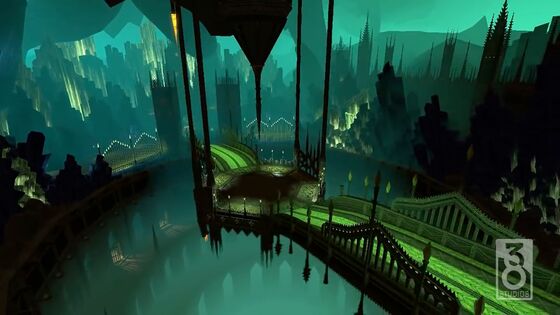

The game looked gorgeous, too. It was full of sleek medieval castles and vivid environments—humongous waterfalls, ancient statues, craggy mountains, menacing underground cities lit with sickly shades of neon green. But it was still years away from release, and 38 Studios had to start paying back the Rhode Island loan right away. Throughout 2011, reports later suggested, 38 Studios had a burn rate of more than $4 million a month. This would eat through most of the loan in a year, because 38 Studios only received about $49 million, with the banks keeping the rest. After the studio’s collapse, Schilling said the shortfall was partially to blame.

When Andy Johnson started working at 38 Studios in January 2012, he went around its headquarters at One Empire Plaza in Providence introducing himself to executives, designers, and developers. As part of his job, which was to facilitate the translation of the games into other languages, he put together an estimated release schedule. Even his most conservative estimate showed that there would be no way for Copernicus to come out that year.

The following week, Johnson brought the schedule to one of 38’s vice presidents, who shut the door and asked him who else had seen it. “Everything started cascading into lunacy,” he says. Word spread among the other vice presidents and executives, who would barge into Johnson’s office and interrogate him about the disappointing document. “I was like, ‘Oh crap.’ I had just done my due diligence of trying to figure out sizing, scope, estimate time for all this stuff,” he says. “I felt like I’d uncovered some big secret.”

Soon afterward the studio imposed a hiring freeze. This left Johnson unable to do his job, while colleagues had taken to locking themselves in their offices, working on spreadsheets or polishing their résumés. In March, 38 Studios stopped paying many of its external vendors. On May 1, it failed to make one of its bank loan repayments, putting the loan into default.

The studio was making progress on Copernicus, and some of the ideas it was exploring seemed groundbreaking by the standards of the day. Players could change the outcome of the world based on how well they performed. If one group of gamers defeated the evil dragon, their world would enter a celebratory state. Another group might fare worse, failing to beat the dragon and watching it destroy their cities with molten lava.

Most of the staff had no idea of the trouble they were in until later that spring. On May 14, Lincoln Chafee, who had succeeded Carcieri as governor, told reporters that his goal was “keeping 38 Studios solvent.” Those four words spooked potential investors that Schilling had been wooing, including gaming giants Tencent Holdings Ltd. and Nexon Co. “The conversations ended immediately,” Schilling later said on a Boston radio show. “I knew then that we were in a world of hurt.”

It became clear to most employees the following day, which was supposed to be payday. Heather Conover, a designer, remembers walking to the office when a colleague asked if she had been paid. When they arrived at the office, Conover logged in to her checking account. There was no deposit. “We all sort of had this sinking feeling as it started spreading,” she says.

The next few days were chaos—a blur of angry all-hands meetings and frazzled employees. Management asked them to keep coming in, while reporters with cameras and microphones camped outside the office. Some developers didn’t bother showing up. Others tried to bring home the office equipment. “People were picking up desktops and monitors, saying, ‘Screw this, I’m taking this, that’s my payment,’ ” Johnson says.

Chafee began publicly revealing what 38 Studios saw as proprietary information, like Copernicus’s projected release date (by now June 2013). A longtime critic of the loan guarantee deal, the governor blamed the company’s freewheeling spending. In a scathing newspaper editorial a few years later, Schilling called Chafee a “liar and a phony.”

Through the end of May, many workers kept showing up even though the paychecks never came. A few people put together a two-minute YouTube trailer showing off Copernicus, partly as a last-ditch effort to try to persuade some other video game publisher to hire them but also to ensure that their work would still be seen by the world even if no one ever played the game.

Some of 38 Studios’ employees still believed Schilling would find a way to keep the company afloat, just like he saved the 2004 Red Sox. “I kept thinking, ‘They’re going to pull a rabbit out of their hat,’ ” says Ang. “ ‘They’re going to work something out.’ ”

Instead, on May 24, an email went out to everyone who worked for 38 Studios, telling them it was their last day. The note came not from Schilling, but from Bill Thomas, the studio’s chief operating officer—and also the uncle of Schilling’s wife. The note, which was bizarrely cold for a company whose executives often talked about the organization as a “family,” cited an “economic downturn” within the company. “A company wide lay-off is absolutely necessary,” wrote Thomas. “These layoffs are non-voluntary and non-disciplinary. This is your official notice of lay off, effective today.” There was no more health care, no severance—employees wouldn’t even get the money they were owed from their final paychecks.

The collapse of 38 Studios devastated Schilling. Bankruptcy filings later showed that when the studio collapsed it was $150 million in debt, with millions owed to investors, vendors, and insurers. Schilling said he’d put $50 million of his own money into the company and was now “tapped out.” In the years following the studio’s closure, he became a right-wing provocateur, advocating for Donald Trump and sharing conservative memes on Facebook and Twitter, where he spent a great deal of time attacking liberal politicians, progressive causes such as Black Lives Matter, and just about every news organization that wasn’t named Fox. In 2015, Schilling was suspended from his job as an ESPN analyst for posting images comparing extremist Muslims to Nazis. A year later, ESPN fired him for sharing transphobic memes on social media.

As he attacked Democrats and made racist remarks in public, Schilling was giving depositions and watching his company’s assets sold off in a bankruptcy auction. But as with all studio closures—at least a dozen have shut down since 2018—perhaps the strongest burden fell on the employees.

Hundreds of former 38 Studios employees were left stranded in Rhode Island, where there were no other video game companies or jobs. Those who wanted to stay in the video game industry had to again uproot their lives and move to new cities. In the weeks following the shutdown, the video game industry came together to try to help out the displaced employees. Recruiters promoted social media hashtags like #38jobs and flew out to Providence for a job fair. Rhode Island sent representatives to One Empire Plaza so that people could file for unemployment at the office, while some staffers brought in canned food to help struggling co-workers.

For Ang, the kicker came in the form of a letter from MoveTrek Mobility, the company that 38 Studios had hired to sell his old lake house in Massachusetts. Turns out it hadn’t sold. And somewhere in the fine print of his contract, Ang had agreed that if 38 Studios ever faced financial trouble and stopped paying the mortgage, the obligation would fall back on him. Panicked, Ang called up MoveTrek and asked what was going on. “They said, ‘It means you have to pay the bank on the loan,’ ” he says.

Adapted from the book Press Reset: Ruin and Recovery in the Video Game Industry by Jason Schreier. Copyright 2021 by Jason Schreier. Reprinted with permission of Grand Central Publishing. All rights reserved.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.