Private Equity Won Big on Lululemon, and It’s Not Done Yet

Private Equity Won Big on Lululemon, and It’s Not Done Yet

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Shares in Lululemon Athletica Inc. have almost doubled in the past year, part of a remarkable turnaround that’s also a win for the private equity investor that set out to repeat one of its most successful bets. Boston-based Advent International Corp. first made a minority investment of $74 million in the activewear retailer in 2005, then rode a wave of popularity as consumers, led by affluent women, embraced the notion of athleisure. The retailer went public, and by 2009, Advent had sold all its shares, pocketing eight times its investment, according to people familiar with the situation. Then it came back with another investment in 2014.

The $845 million deal happened after Lululemon founder Dennis “Chip” Wilson called Advent managing partner David Mussafer in 2013 looking for advice. The company’s growth was slumping, and the retailer was still trying to recover from an embarrassing recall of some of its popular black yoga pants that turned out to be a little too see-through. Mussafer and Wilson convened at Shutters, a beachside hotel in Santa Monica, Calif., and some months and several more meetings later, Advent agreed to buy half of Wilson’s stake in Lululemon, giving Advent two seats on the board of directors. Although the company stayed public, and Advent was never a controlling shareholder, the transaction was a turning point. Private equity firms have a reputation for stripping companies for parts, but Advent helped reassemble and redirect the company into one that’s quintupled its total market value in a little over five years, to more than $30 billion.

Not that the story was entirely happy. Shortly after the deal, Wilson fell out with Mussafer and Advent, agitating unsuccessfully for a board overhaul. Advent and Lululemon hired an independent consultant to assess the board; Wilson hired one, too. Lululemon went with its consultant’s recommendation. Wilson left the board, but didn’t go quietly, agitating for change at a subsequent annual shareholder meeting. “The two of us together could have been brilliant,” he says, referring to Advent. “And I think they were the first time they came in.”

One thing Wilson and Mussafer agreed on was that Lululemon was something of a mess. Advent and the directors identified three ways to turn things around: The brand should appeal to men as well as women, it should be global and not just North American, and it should pursue a much more aggressive online strategy.

All of that falls squarely into the private equity playbook and this may be a model for future investments, Mussafer says. “The idea of applying a private equity approach is what a lot of public companies need.” But it requires commitment. The quarter-to-quarter pressures applied by Wall Street remain. “If we had gotten it wrong or misjudged, I’m not sure Lululemon would’ve continued as an independent company,” Lululemon Chief Operating Officer Stuart Haselden says. “We would’ve gotten swallowed up.”

Haselden, who joined in 2015, knows a lot about the intersection of private equity and retail; he worked at J.Crew Group Inc. when TPG Capital did its own, so far less successful, reinvestment in that retailer. At Lululemon, Haselden moved aggressively to eliminate “pockets of profound dysfunction” in the supply chain. Ultimately, the team widened gross margins, a measure of profitability, by 8 percentage points. Similarly, the management team gutted and rebuilt its digital infrastructure to enable online selling. (On Dec. 9, Lululemon announced Haselden is leaving the company early next year; he’s becoming the chief executive officer of Away, an online luggage retailer.)

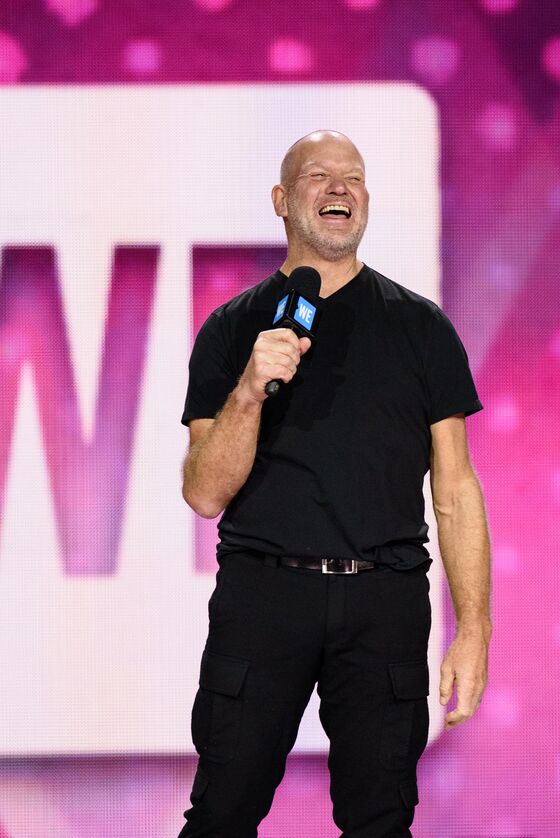

Even as the Advent-led board pulled all those levers, the drama wasn’t quite over. Laurent Potdevin stepped down as CEO in early 2018 in part because of a consensual relationship with a subordinate. His departure led the board to hire current CEO Calvin McDonald, who was running Sephora when Lululemon tapped him. His chemistry with Mussafer was on display this fall during an interview before regular hours at a store in Manhattan. “The balance of the conversation is usually a little bit on growth and very much on the financial metrics,” McDonald says. “Most of our conversation was dreaming the dream of what could be and what will be, and what the potential is for the brand.”

Wilson, despite his misgivings about the aftermath of the 2014 transaction, is a fan of McDonald and says the company has “an incredible future.” He’s still the fifth-biggest owner of the stock.

Mussafer remains on the board as Lululemon’s lead director, and while the firm has sold down its position since the 2014 deal, it remains a top-10 holder, with a roughly 2% stake. He takes a long view, all the way back to growing up in Alabama with a father who had his own store, a catalog showroom. In a world where affluent shoppers who comprise the majority of Lululemon’s customers are rejecting fast fashion in favor of fewer, higher-quality (and higher-priced) pieces, Mussafer likes Lululemon’s chances. The company just opened a flagship store in Chicago and is taking a page from Amazon Prime in experimenting with a membership program. “One of the first lessons I learned in retail is that it’s on the front lines of any disruption,” he says. “We complained about the emergence of Walmart 20 years ago and, today, Amazon. You’re going to have to change and evolve.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Pat Regnier at pregnier3@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.