PredictIt Owns the Market for 2020 Presidential Election Betting

PredictIt Owns the Market for 2020 Presidential Election Betting

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Voting in the Democratic primaries doesn’t start for six months. Candidates have yet to trek to the Iowa State Fair for their obligatory deep-fried photo opportunities, and many voters are only just waking up to the election looming in the fall of 2020. But on PredictIt, a political-betting website built by a group of researchers in New Zealand, a shadow primary has already been raging for months.

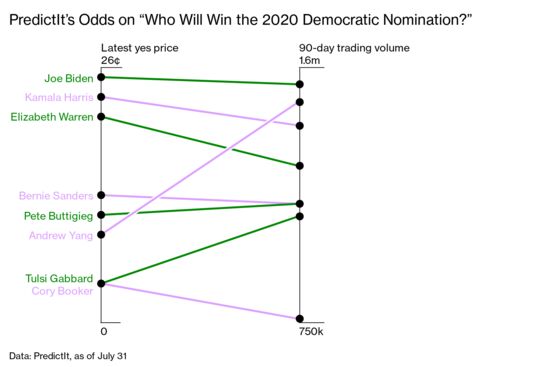

Former U.S. Representative Beto O’Rourke of Texas was the early front-runner, with traders giving him a 20% chance of winning as of January. California Senator Kamala Harris passed him later that month when she made her candidacy official, but by March, Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont was the leader. Harris moved back into the front after calling out former Vice President Joe Biden in their first debate for praising the genteel segregationist senators of the past, but after their second faceoff on July 31 Biden regained a decisive lead.

Since it went live in late 2014, PredictIt has become the go-to place to gamble on U.S. politics. The site makes it as easy to wager on how many tweets President Trump will send this week as it is to buy a stock on ETrade. Trading volume has been running at about 250 million shares per year, estimates Jon Hartley, an economics writer and researcher, with each share representing a potential payoff of $1. (PredictIt says that figure isn’t accurate and won’t share its own numbers, but Hartley says it’s derived from data provided by the site.) PredictIt’s markets are routinely cited by the press as evidence of whom the smart money favors.

Betting on politics is illegal in the U.S. PredictIt owes its existence to an exemption for academic research granted five years ago by the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) to Victoria University of Wellington in New Zealand. To get permission to operate the site, the school said professors would run it for free and the data would be used in academic studies.

PredictIt is similar to a stock market: Gamblers post offers to buy and sell “shares” in candidates at prices up to $1. If you wanted to bet that Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren would be the Democrats’ 2020 nominee after her second debate on July 30, you could have bought a share the next day for 21¢. If she wins, you’ll get $1. If she loses, her stock goes to $0, and you lose your money. The site collects a 10% fee on winnings and a 5% fee on withdrawals. Individual bets are limited to $850, per the agreement with the CFTC. But with so much politics to gamble on, that hasn’t put much of a damper on the action. Political day traders try to capitalize on swings in opinion long before votes get cast.

Aaron Reese, a 34-year-old MBA student at Rice University, says he often makes enough money on PredictIt to pay his rent. He says Trump’s surprise victory created a group of bettors who don’t trust polls, which means easy money for him. “People don’t believe reality anymore,” Reese says. “People think every poll is fake and nothing matters anymore.”

Victoria University owns a small percentage of PredictIt and collects a monthly administration fee, according to Anne Barnett, who runs a program at the school that helps professors turn research projects into businesses. The site’s operations have largely been farmed out to a political software company called Aristotle Inc. John Aristotle Phillips, its founder, says the school was already running a similar site and he helped it expand into the U.S. But don’t call it gambling, he says. He prefers the term “forecasting.” “It’s an antidote to fake news,” Phillips says. “If a trader makes a buying or selling decision on something that’s inaccurate or misleading, they’re going to lose their money.”

A century ago, bookies openly took illegal political bets at New York City’s stock exchanges and hotels. With no public polls to report on, newspapers wrote about big bets placed on candidates. Election wagering fell out of favor once Gallup introduced a poll that accurately predicted Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s 1936 presidential victory and New York legalized betting on horse races, according to economists Paul Rhode and Koleman Strumpf.

Chances are that at some point this election season someone will tell you that prediction markets are a better gauge than polls. They developed this reputation after bettors on a similar site called InTrade correctly called the presidential election in 49 of 50 states in 2012 and 47 states in 2008. But one 2012 analysis showed that the prediction market had done no better than pundits who relied on polling averages—unsurprising, given most traders lean on those indicators, too. InTrade was based in Ireland and took bets from Americans until it became too well-known during the 2012 election and U.S. regulators sued it. The site closed the next year. The Iowa Electronic Markets, another political-gambling site, got an exemption from antigambling laws in 1993, but its website is outdated and difficult to use. It offers just a couple of events to bet on and only allows gamblers to deposit $500.

To justify the academic exemption that allows it to ignore gambling laws, PredictIt provides its data at no cost to researchers. Phillips says they study the data “to understand why markets are as predictive as they are.” A spokesman for Aristotle declined to say how much the company has made from PredictIt, but he said that the site has yet to earn back its startup costs.

When Bloomberg Businessweek contacted dozens of the people listed on PredictIt’s site as “our research partners,” none said they had done any work of the sort Phillips described, though a handful had made use of the odds as a control variable in other studies. Several were surprised to see their names listed. “That is a bit misleading,” says Paul Armstrong-Taylor, an economics professor at the Hopkins-Nanjing Center in China, who says he asked for the data on behalf of a student who never used it. The Aristotle spokesman said Armstrong-Taylor’s name would be removed and provided a list of 15 papers and presentations that made use of PredictIt data over the past few years. (PredictIt says all the researchers listed signed an agreement to receive data.)

Reese, the trader, says the best bet on PredictIt has been selling shares of Andrew Yang, the long-shot candidate who’s an internet favorite. His fans are driving up his stock price to show their support—up to 8¢, double U.S. Senator Cory Booker’s—and there’s not enough smart money to balance them out. “When prices start moving, people will assume other people know something they don’t,” he says. “You have to figure out what you think the real probability is.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jillian Goodman at jgoodman74@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.