Powell Speaks, Trump Tweets, China Reacts, Markets Freak. Repeat

Powell Speaks, Trump Tweets, China Reacts, Markets Freak. Repeat

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- The ups and downs of asset prices on any given day are being determined, more and more, by the words and actions of three men.

First, of course, is Donald Trump, who has rediscovered his power to send markets soaring—or into a tailspin—with less than 280 characters on Twitter. Then there’s U.S. Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell, who repeatedly finds himself on the receiving end of nasty Trump tweets for abiding by his mandate to do what’s best for the U.S. economy, which isn’t necessarily always the same thing as what’s best for the sitting president. And in Beijing, it’s Xi Jinping, the president of China who sits atop a Communist Party in which politicians and central bankers famously sing from the same hymnal, at least when the audience is outside observers.

The financial markets have been like a mosh pit where these three players bang against one another. Powell, under pressure from Trump to cut interest rates aggressively, sent markets reeling by signaling the central bank’s rate cut last month was a “mid-cycle adjustment” and not the start of an aggressive loosening of monetary policy. The very next day, Aug. 1, Trump exacerbated the sell-off by saying he would place tariffs on practically any U.S. imports from China that don’t already have them, starting in September. The response from Beijing on Aug. 5 caused the biggest waves in global markets, as the People’s Bank of China allowed its currency to depreciate by the most since 2015 and reach more than 7 per dollar, a threshold it had prevented the yuan from crossing in recent years. China also asked state-owned companies to suspend purchases of U.S. crops, renewing pressure on the beaten-down prices of American corn and soybeans.

With each of these collisions, the fragility of the global economy and markets is exposed. It seems increasingly possible that something big and important is broken. Investors who’d believed U.S.-China relations were stabilizing, if not improving, were caught on the wrong foot when tensions abruptly escalated. The prevailing assumption that President Trump won’t allow the trade war to continue through the 2020 presidential campaign season is being reconsidered, as the two sides appear further apart than ever. Economists at Goldman Sachs Group Inc., for example, no longer expect a trade agreement before the election and see the Fed cutting its benchmark interest rate two more times this year in an effort to counteract the economic damage that will be done by the impasse.

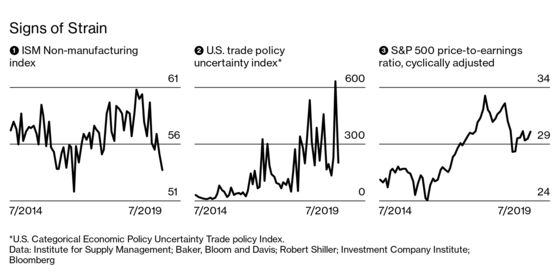

The constant whiplashes in expectations can be seen in an index that measures how often news stories mention uncertainty surrounding U.S. trade policy. It almost tripled in June to a 25-year high, before dropping by more than half in July after a comparatively uneventful stretch. The drama of August isn’t yet reflected in the index, which is calculated monthly.

As troubling economic data pile up, the question being openly debated on Wall Street is whether lower borrowing costs will be enough to fend off a recession. An Institute for Supply Management index for the U.S. manufacturing businesses that Trump’s policies were meant to support dropped to an almost three-year low of 51.2 in July. A similar gauge of the service industries had dropped from 60.8 in September to a three-year low of 53.7 in July. For both indexes, readings below 50 are a sign that economic activity is shrinking. In Europe, whose factories are caught in the crossfire between China and the U.S., manufacturing barometers already point toward recession. Growth in U.S. corporate profits, which the tax cuts put on steroids last year, has all but halted, and forecasts for the timing of a rebound keep getting deferred.

As the trade war morphs into a potential currency war—in which countries race to devalue to get a competitive edge for their exports—there are whispers about how and where the tensions could escalate further. Could the U.S. thumb its nose at China and sell F-16 fighter jets to Taiwan? Or could Washington signal support for the anti-Beijing protesters who’ve paralyzed Hong Kong this summer? And what could be at risk among more than a quarter of a trillion dollars of U.S. investments in China since 1990?

All these questions are arising in the dog days of summer, a time of year when Wall Street’s vacation calendars are jammed and markets seem especially easy to rattle. Measures of stock market volatility tend to rise on average in August, and some of the ugliest swoons in equities over the past decade have occurred in this month. The S&P 500 index has shed about 6% from its last record, in late July, leaving it below the peak it reached in January 2018 at the height of optimism surrounding Trump’s corporate tax cuts. Even the most reliable big spenders in the market these days—corporations themselves—have had trouble keeping share prices afloat. Shares of Google parent Alphabet Inc. surged almost 10% after the company announced a $25 billion share buyback plan on July 25. The stock proceeded to lose almost all of that gain in the following week.

Before the latest swoon, there were signs that some investors were getting nervous about the balance of risk and reward offered in the market. Some measures of valuation look high. Warren Buffett’s preferred metric, the ratio of the total market value of U.S. stocks to gross domestic product, is at about 1.49, higher than it was just prior to the financial crisis. The cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings ratio, based on the last 10 years of earnings, is about 30, well above the 50-year average of 20. Both measures capture roughly the same thing: how much it costs to buy a piece of the wealth that businesses are generating. Neither number can tell you when the market is about to turn, but they both suggest prices are high.

For Buffett, there doesn’t seem to be much worth buying at current valuations. The latest earnings report from his Berkshire Hathaway Inc. showed the holding company sold more stocks than it bought in the second quarter, and its pile of cash rose to a record $122 billion. He’s not the only one sitting on the sidelines: assets in money-market mutual funds—the mattresses investors tuck money under when other choices look too risky—have climbed to an almost 10-year high of $3.3 trillion.

The recent rush into safe havens sent gold to a five-year high and triggered a rally in Treasuries that pushed 10-year yields to their lowest since Trump was elected in 2016. (Yields drop when prices rise.) At the same time, rates on three-month Treasury bills were higher than those on 10-year bonds—a phenomenon known as a yield-curve inversion that’s widely considered a reliable warning of an impending recession. The lower long-term yields signal that markets expect interest rates to come down in response to weak economic growth.

“We may well be at the most dangerous financial moment since the 2009 Financial Crisis with current developments between the U.S. and China,” tweeted Larry Summers, Treasury secretary under Bill Clinton and economic adviser to Barack Obama. One might detect a partisan edge in that comment, but there’s no doubt markets are trying to see their way through a lot of potential chaos. Bulls may hope that Trump will tweet about a breakthrough with “his good friend Xi,” and stocks will be off to the races again. But for now the cacophony in the mosh pit just seems to get louder and louder.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Pat Regnier at pregnier3@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.