The EU Bankrolled a Rebellion That Threatens to Tear It Apart

The EU Bankrolled a Rebellion That Threatens to Tear It Apart

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Governments across Europe are showcasing their plans to reinvigorate economies after the pandemic, and nowhere more so than in Poland. Ruling Law & Justice party officials have visited dozens of towns to hand out replica checks to local leaders displaying how much is headed their way. The slogan on billboards and buses declared the government had found “770 billion zloty for Poland.” That’s equivalent to $190 billion, a full one-third of the nation’s economic output.

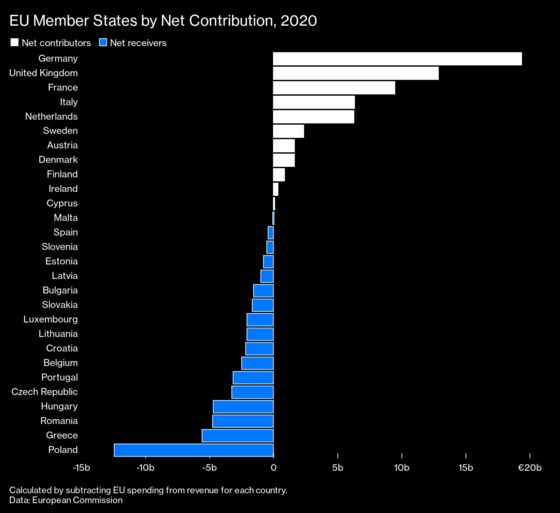

What the ads didn’t mention was the source of so much of the money: the European Union. Poland is the biggest net recipient of EU funding and yet—along with ally Hungary—has become its biggest problem. The flow of money is now the key battleground in a war with Brussels over issues including the rule of law, LGBTQ rights, and media freedom.

The EU threatened last month to withhold €36 billion ($41.2 billion) from its Covid-19 recovery fund unless Poland rows back on changes to its justice system that culminated with a unilateral decision to end the primacy of European law in the country. Hungary faces similar action over its erosion of what the EU says are the bloc’s core values. Both governments are outraged, with Poland most recently saying now is not the time to be making threats when it’s protecting Europe’s eastern flank from migrants coming illegally through Belarus.

But the awkward truth is that the populist leaderships of Jaroslaw Kaczynski in Warsaw and Viktor Orban in Budapest have been using European largesse for years to tighten their grip on power and undermine EU unity. Put bluntly, Brussels has bankrolled an insurrection it’s now trying to put down by making future cash transfers contingent on adhering to its model of democracy.

Hundreds of billions of euros of EU cash has gone toward everything from new hospitals and schools to highways and high-speed rail links, funds that are given to poorer regions to catch up with richer ones. It’s also been channeled into social programs and enabled “great possibilities of patronage” as leaders used funds and contracts to reward political allies, says Timothy Garton Ash, professor of European Studies at Oxford University.

“The EU has done more to sustain these governments than it has to constrain them,” he says. “There’s a growing understanding in the EU that something has gone wrong here and that the erosion of democracy and the rule of law in Hungary and in Poland is a threat to the entire legal order and indeed the democracy and legitimacy of the EU.”

The challenge is how to bring the countries into line without risking a Brexit-style fracture. The U.K.’s departure served as a warning about how messy—and damaging—a divorce might be, though it also emboldened the narrative in Hungary and Poland that the EU is a diminished power.

Weaponizing European financial support carries risks on both sides. Poles and Hungarians overwhelmingly support EU membership, for the freedom to travel and work denied during communism, as well as the money. Their governments, though, have assembled formidable state media machines that depict the EU as the bad guy even as ministers spend its money.

The mood in Germany, the largest contributor to European coffers, is that the EU must not back down, though German Chancellor Angela Merkel has expressed the need to tread carefully and warns against punishing populations for their governments’ misbehavior. Countries like the Netherlands want a tougher line on how rogue members are spending the money of Western European taxpayers, and the new German government being formed will be without Merkel.

The European Commission in Brussels had deployed its usual blend of threats, delay, and hope that domestic electoral forces will come to the rescue. What changed the calculus was the ruling on Oct. 7 by Poland’s top court that the country’s constitution overrides some EU laws, a no-no for member states. Poland is being fined €1 million a day by the EU Court of Justice until it rolls back the level of scrutiny that politicians have over judges.

Hungary also faces possible daily fines because of its non-compliance with an EU court ruling related to asylum law. The Orban government’s request to the country’s constitutional court to review the EU order was “unacceptable” because it challenged the primacy of EU law, Justice Commissioner Didier Reynders said in Budapest on Nov. 12.

The trouble for the EU is that it’s not set up to play the bad guy, says Marek Prawda, the veteran Polish diplomat who served as head of the European Commission’s representation in Poland from 2016 to March of this year. Most measures require consensus among member states, meaning Hungary can veto action against Poland and vice versa. They are also legally challenging the EU’s plan to attach strings to the pandemic recovery funds, with the EU’s advocate general in the case due to issue a nonbinding opinion on Dec. 2.

“All of the EU’s punishment mechanisms are only created so that they don’t have to be used,” says Prawda. “They should be visible and hang on the wall like the sword of Damocles, but the EU is completely hopeless if a member state isn’t afraid of these tools of torture.”

There’s also little EU officialdom can do if the bloc’s funds are used to sustain a network of political patronage. Last month, European Parliament lawmakers called on Hungary and Poland to address rule-of-law concerns and corruption before accessing billions of euros in a recently set up Covid-19 recovery fund.

Deputy Justice Minister Sebastian Kaleta suggested in an interview with Bloomberg on Nov. 5 that the country may stop paying its membership fees to help mitigate any loss—especially, he said, given the cost of protecting the EU’s border with Belarus. “As a loyal EU member we pay a contribution to the budget, we make our market available to western companies and we are entitled to these funds,” Kaleta said.

The Hungarian government says any allegations of impropriety should be handled with “seriousness.” “Anyone aware of breaches of law (be it national or EU law) or corruption cases should refer them to the competent authorities,” Orban’s office said in a response to questions for this article.

It’s hard to overstate the symbolism of the EU’s expansion into the former Eastern Bloc in 2004. These were countries that spent four decades as communist satellite states of the Soviet Union and saw a series of uprisings in the name of democracy brutally crushed. Kaczynski, 72, was part of the Solidarity movement that topped the regime in 1989, while Orban, 58, made his name as a young pro-European, Western-leaning anti-communist.

The EU has plowed almost €200 billion into Poland alone since it joined the bloc and another €68 billion into Hungary, which is a quarter of Poland’s size. The EU has strict procurement rules when it comes to disbursing the money, though member states are relied upon to police them. In recent years, how the money was spent has become more political.

“Loyalty to the government is the most important factor in the distribution of EU funds,” says Jozsef Peter Martin, director of Transparency International in Hungary. “For a long time the EU didn’t do anything, it turned a blind eye. It’s unclear if it’s too late by now.”

There are myriad ways in which EU funding distorts the economic and political system, according to Istvan Janos Toth, director at the Corruption Research Center in Budapest, who has analyzed hundreds of thousands of public procurement contracts. Pro-government municipalities, for example, are much more likely to get EU funding, he says.

There’s also less competition. From 2016 to 2020, the proportion of EU funds spent on projects for which there was only a single bidder was highest in Poland and the Czech Republic at 51%, followed by Hungary at 40%, according to European Commission data.

One prominent beneficiary is Lorinc Meszaros, a childhood friend of Orban and Hungary’s richest man. Toth calculates that Meszaros’s companies have won $2.5 billion in EU funding since 2011, either alone or as part of a consortium, most of it while he was still a ruling party mayor of Orban’s hometown.

In 2017, more than 20% of the $5.5 billion in EU funding received by Hungary went to contracts won by bidders that included a Meszaros company, Toth says. A year later, Meszaros’s media empire backed Orban’s reelection bid, helping him win a fourth term, in part by disparaging the EU as a waning power.

Meszaros Group, in a written reply to Bloomberg questions, said there’s “no criteria relating to political connections” in the disbursement of EU funding and therefore allegations that the companies may have benefited from their owner’s relationship with the prime minister were “meaningless and irrelevant.”

“The EU’s money has been used to build and then sustain an illiberal state in Hungary,” says Agnes Urban, an economist at Mertek, a think tank that monitors media freedom in Budapest. “It’s the essence of Orban’s regime.”

The issue is that the EU was effectively built on trust. That was laid bare during Greece’s financial crisis, which was triggered by the government admitting it had cooked the books.

In Poland, ministers opening new roads and bridges boast the spending comes down to their prudent budgeting rather than EU transfers. The EU financing system has effectively enabled the government to promote party interests, says Piotr Buras, director of the Warsaw bureau of the European Council on Foreign Relations, a pro-EU think tank. “Poland has created a system where EU funds are also used to keep what is effectively an anti-EU regime in power,” says Buras.

While the EU repeatedly says that it’s not too late to salvage the countries as model members, it’s going to be down to the electorates in both to do the job.

Tens of thousands of people took to the streets of Polish cities in October to protest the move to dilute the status of EU law. Donald Tusk, the former European Council president who served as Polish premier from 2007 until 2014, is back on the front line of Polish politics to challenge his nemesis Kaczynski, the Law & Justice leader. Elections won’t take place until the year after next, though the governing coalition looks more fragile after one party opposed a controversial new media law that has angered the U.S.

In Hungary, opposition groups have united to take on the ruling Fidesz party in next spring’s election, where Orban will be gunning for a fourth-straight term and his fifth in total. The opposition’s candidate for prime minister, Peter Marki-Zay, will make the question of Hungary’s relations with the EU and how money is spent a key platform of the campaign. “If the economy doesn’t work then the regime fails,” says Marki-Zay. “The fact that Orban hasn’t and that he’s been economically successful is entirely down to EU money.”

Orban and Kaczynski themselves scoff at the idea of leaving the EU, and the status of both countries as member states is safe for now. Yet the game of chicken with Brussels has led to serious questions over what the future holds, and words carry more weight.

Hungarian Finance Minister Mihaly Varga, a moderate in Orban’s cabinet, said earlier this year the country’s membership may be reconsidered once it becomes a net contributor to the EU budget, possibly by the end of the decade. The word “Polexit” is now part of the political vernacular in Poland. Losing Hungary would be unfortunate for the EU. Losing Poland—its biggest investment in post-Cold War integration by far—would be a disaster. —With Alberto Nardelli, Stephanie Bodoni, Piotr Skolimowski, and Marton Kasnyik

Read next: Economic Recovery From Covid Shows Countries Need More Than Just Vaccines

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.