Brazil’s Central Bank Built a Mobile Payment System With 110 Million Users

Brazil’s Central Bank Built a Mobile Payment System With 110 Million Users

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- On a Sunday afternoon at a busy intersection in central Brasília, a woman asks passing motorists for money. Her cardboard sign, written in marker in Portuguese, reads: “Need help. Hungry. I accept Pix.”

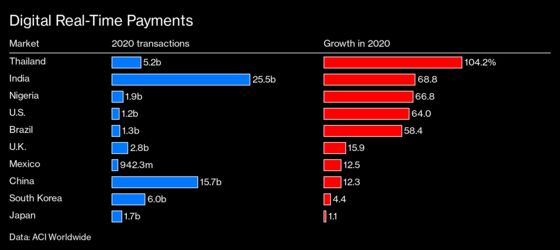

Pix, a system which allows fast money transfers over smartphones, has become ubiquitous in the 11 months since it was launched by Brazil’s central bank. All that’s needed to send cash to someone is a simple key they’ve set up, such as an email address or phone number. Similar to the privately owned Zelle in the U.S., Pix works through multiple apps from banks and other digital wallet services. It’s already been used at least once by 110 million Brazilians and about $89 billion has moved through the network. Brazil now registers more instant transfers than the U.S.

The launch of Pix turned out to be well-timed. With businesses closed during the pandemic, the use of cash at points of sale decreased by 25% in 2020, according to a report from technology consultant FIS. Informal work boomed, accounting for 80% of the new jobs added in Latin America’s largest economy in the first three months of 2021. Pix made paying people digitally almost as easy as using paper money. “We expected considerable acceptance from individuals, and we knew companies would come later on,” says Carlos Eduardo Brandt, the chief of management and operations for Pix. “But in terms of magnitude, it surprised us.”

Fast digital money has some of the risks associated with cash. A notorious crime in Brazil is “express kidnapping,” in which criminals grab victims, take them to an ATM, and force them at knifepoint or gunpoint to withdraw the maximum amount possible. Pix, it seems, is the new ATM: Muggers skip the trip to the cash machine and simply make people transfer their savings via an app. Although Pix transactions are traceable, in some cases criminals may be using accounts in others’ names. Speaking at an event in São Paulo, central bank President Roberto Campos Neto attributed the thefts to a general uptick in crime as the economy has reopened, adding that “our platform allows us to make adjustments very easily.” Policymakers in August added safeguards similar to those put on ATMs, such as limiting the amount one can transfer at night, when such assaults are most common.

In July, Pix broke its own record of 40 million payments in one day. Most of those were person-to-person transfers, which is how Renata da Silveira Pires, the owner of a small cat-sitting business in Águas Claras near Brasília uses it. “Before Pix existed, I had to have accounts in many different banks, so that my clients wouldn’t have to pay the fee to send money to another bank—which could be 30% of the cost of one of my visits and would weigh heavily on customers,” she says. “Now I just need to have one account. This helps me control my finances.” She often works on weekends and holidays, when pet owners are traveling, and she’s now able to receive payment immediately instead of having to wait for banks to open.

One of the goals of the Central Bank of Brazil in launching Pix is to get more people inside the formal financial system. “We want to offer an infrastructure able to meet all the needs of our society, especially in those sectors where needs are not currently met,” Brandt says. But Pix by itself won’t be enough. Brazilians still need a bank account or some kind of payment service to use it, and about 30% still don’t. Initiatives such as Pix “make payments more efficient, especially for those who already have bank accounts, but achieving financial inclusion is a whole different thing,” says Liliana Rojas-Suarez, director for Latin America at the Washington-based Center for Global Development. She says countries in the region also have to address costly regulations and low trust in the financial system.

The hope for Pix is that by speeding and simplifying payments, banks and financial technology companies will be goaded to innovate and provide new, more accessible services. The country is particularly fertile ground for digital payments: Brazilians spend more time on social media than people in any other country in the Western Hemisphere and have the fifth-largest online population, according to GlobalWebIndex. In recent years, fintechs such as the Warren Buffett-backed Nubank have drawn customers away from traditional Brazilian banks. Nubank is eyeing an initial public offering that could give it a market value of $55 billion.

Pix already faces competitors, such as a new payment service through the Facebook-owned messaging system WhatsApp. But the central bank aims to keep expanding Pix’s reach. It will soon offer ways for users to make payments when they aren’t connected to the Internet. Pix is also working on allowing international transfers as well as making it possible for users to get cash from retailers as an alternative to ATMs. “We haven’t even started yet,” said Campos Neto at an event hosted by the newspaper Folha de São Paulo in August. “I would say we have only used 5% of its potential.”

Read next: Afghanistan’s Economy Is Collapsing as Cash Disappears

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.