Philly Learned the Hard Way to Pick Its Vaccine Distributors Carefully

Philly Learned the Hard Way to Pick Its Vaccine Distributors Carefully

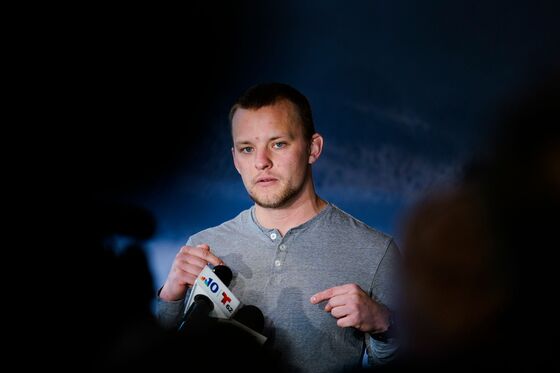

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- By the look of things, Andrei Doroshin, the 22-year-old grad student given the keys to Philadelphia’s vaccination program, really believed his own baloney. In the lobby of his apartment building in the gentrified neighborhood of Fishtown, Doroshin had called a press conference to address the failure of his nonprofit, Philly Fighting Covid Inc., to make much progress. Absent a strong, coordinated effort, the grad student’s team had fallen well behind the vaccination rates of New York City and others, but Doroshin seemed to think that was somebody else’s fault. “The city chose us because we were the only ones who had a plan,” he said, audibly seething. “I am here, forced to defend myself against another example of Philadelphia’s dirty power politics.” When a reporter asked for clarification on that, Doroshin—arms crossed—interrupted her: “I still also don’t understand.”

The press conference, held in late January, was a low moment for my hometown, close behind the Eagles’ 2005 Super Bowl loss to the Patriots and the time we had to abolish our traffic court after nine judges were charged with criminal conduct. Philly is a scrappy city whose residents are loyal to the end, but the PFC scandal left us feeling a bit exposed and, in some minds, validated Donald Trump’s statement during a presidential debate that only bad things happen here. When Philly makes the news, it’s for misdeeds real or imagined, not for triumphs like our plethora of pandemic-related mutual aid organizations, the founding of American democracy, or Jazmine Sullivan’s singing voice. Doroshin’s gambit added to the bad-news pile.

It made some sense, though, how we got here. When the city put Doroshin in charge of its vaccine rollout a month earlier, he’d looked much more capable, and Philly needed all the help it could get. Deep in the third Covid-19 surge, more than 2,500 new cases of the coronavirus were reported in the city during a typical day. Vaccines were just starting to arrive, and the logistical challenges for marginalized populations remained daunting. How could the poorest big city in America effectively vaccinate its 1.6 million citizens?

Philly has its strengths in that department. The city is home to a world-class med school as well as the first hospital in colonial America, founded by Benjamin Franklin himself. And yet, to get the job done, we entrusted an untrained young man whose Instagram account for his bulldog, Winston, was packed with jokes about the pandemic being a hoax.

Doroshin did have one thing going for him: His nonprofit had actually helped early on in the pandemic. PFC started out as a handful of Drexel University students who volunteered to make 3D-printed face shields for undersupplied hospital workers. By last summer it had grown into a team of volunteers conducting Covid tests in a parking lot outside a temporarily shuttered Fishtown music venue. City officials gave the nonprofit a grant of about $200,000 to expand the operation and add more testing sites, especially in neighborhoods where tests could be tough to get. These successes made PFC an attractive candidate when Doroshin applied to distribute the incoming vaccines, notwithstanding his otherwise total lack of medical experience. At Christmastime he was the city’s first vaccine provider.

Doroshin’s startup-bro vibe reinforced his bold promises, at least for a while. As he started signing up people to receive shots, he also began appearing on national television, vowing that his group would do its job better than formally trained medical professionals.

But within three brutal weeks, Doroshin’s volunteer-driven nonprofit made very clear that it wasn’t up to the task—and started to seem a lot more like a unique kind of pandemic grift. He quietly turned PFC into a for-profit company, made himself the highest-paid person on staff, abandoned his testing sites in needy neighborhoods, and sneaked vaccines to friends who wanted to jump the line, then flaunted it on social media. He derailed Philly’s vaccine rollout for most of a singularly bad month. By Jan. 5 the city had administered only about 28,000 doses. As Health Commissioner Thomas Farley put it at the time, “In a city of 1.6 million people, that is not enough.”

In a way, falling for someone like Andrei Doroshin was natural. “Our brains are really powerful at justifying things,” says Maria Konnikova, a psychologist and author of The Confidence Game: Why We Fall for It … Every Time. “You become more susceptible to being conned in moments of uncertainty and upheaval. No one knows what is going to happen. But the onus is on you to be even more diligent given what’s at stake.” Doroshin didn’t respond to requests for comment for this story.

Philly is a town that loves to make demigods of its singular figures, whether historical (Franklin), fictional (Rocky Balboa), or somewhere in between ( Gritty). At his apartment press conference, Doroshin firmly ended his bid to join that pantheon. In a gray henley and black mask, looking irritated by the reporters and camera crews he had arranged to be there, he seemed the spiritual opposite of those other Philly icons and their benevolent Philly-proud chill. “I’m hearing rumors in the city right now that certain people were not happy that we were the first to get the vaccine,” Doroshin said at the press conference. That’s one thing he got right, at least.

It’s tough to write a capsule summary of Doroshin’s pre-pandemic achievements, because his résumé is a series of evolving exaggerations. On his LinkedIn page he describes himself as an “entrepreneur, scientist, and philanthropist” whose primary work experience is as a researcher and scientist at Drexel’s neuroimaging lab. (Notable skills include Brazilian jiujitsu and “cooking good sourdough bread.”) But until shortly before this story was published, the LinkedIn page proudly reflected that Doroshin was the founder and chief executive officer of Philly Fighting Covid. “MSNBC called PFC the most innovative Company in Amierca [sic],” the page read last month. Also deleted: Doroshin’s role as CEO of Invisible Sea Inc., which he’d described as the “largest air-quality [nonprofit] in California that worked with the government to mitigate the looming air-quality epidemic.” Maybe he wasn’t especially proud that Invisible Sea had raised less than $700.

Philly, like many American cities, loves an underdog. And though no one could credibly describe Doroshin as an underdog, the sheer improbability of a grad student with no formal medical experience attempting to inoculate a whole city against an out-of-control virus made him seem like one anyway. How unlikely it would be for him to pull it off—that was the stuff we loved around here.

“Thinking outside the box is what it takes,” Deputy Health Commissioner Caroline Johnson told the Today show in early January, before PFC’s implosion. “For people who do have enthusiasm and ideas and can put them into action.” NBC News anchor Stephanie Gosk showed up at the Pennsylvania Convention Center to witness Doroshin’s first vaccination clinic. The center was lined with rows of distanced seats, many of them occupied by health-care workers who otherwise didn’t have access to the vaccine through their jobs. “They’re running a very orderly operation,” Johnson told Gosk.

Doroshin played the part of a Silicon Valley expat: buzzed hair, dressed in a midnight-blue tuxedo jacket over a dark-gray button-down and jeans. On the one hand, it’s not hard to see why the city trusted him. In an interview with Gosk, he spoke confidently and coolly and seemed at once casual and in control. On the other hand, it’s a wonder that anyone who heard any part of that nationally televised interview didn’t think something was extremely amiss. “We don’t think, like, institutional. You know, we’re engineers, scientists, computer scientists, cybersecurity nerds,” Doroshin said. “We think a little differently than people in health care do. We took the entire model and threw it out the window. We said to hell with all of that.”

Doroshin certainly wasn’t thinking institutional. As local news outlets would later report, PFC appeared to be motivated primarily by self-aggrandizement and cash. With the testing contract the company had been given through the city, Doroshin made himself one of its chief expenses as the staff “data logger.”

Yet Philly Fighting Covid had credibility because of its success with testing. “It seemed very organized,” says Rasheed Ajamu, who shares local news on Instagram and Twitter under the handle Phreedom Jawn, a play on Philly’s love for turning “f”s into “ph”s and calling everything a “jawn.” Doroshin has said the team tested about 20,000 people through the fall.

In administering the vaccine, the city intended to work with as many accredited organizations as necessary to distribute shots to the greatest number of people, without guidance or assistance from the federal government. Doroshin, meanwhile, had a 22-year-old’s unearned confidence on his side. With his newfound city government connections, he began pitching his organization as the one to lead the vaccination effort. He made it onto a special city-organized vaccination committee, and in late December, when Centers for Disease Control and Prevention paperwork was available to submit for prospective clinics, PFC was the first to apply. Within a week the city asked Doroshin to run a vaccination pilot program to demonstrate his team’s capabilities.

A few days before the first large-scale clinic was due to open at the convention center on Jan. 8, however, PFC’s chief medical officer (its only licensed doctor) quit and alerted the health department that the operation had quietly reincorporated itself as a for-profit called Vax Populi. The whistleblower also warned the department not to trust Doroshin or his ability to handle vaccinations. By the time Doroshin opened the clinic at the convention center, he’d abruptly backed out of testing sites in low-income neighborhoods.

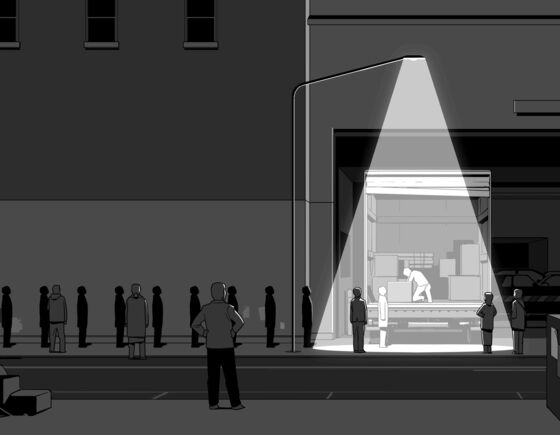

Almost immediately, Ajamu says, it was clear something else wasn’t right. He started receiving messages and comments from followers who’d gotten a first shot from Philly Fighting Covid, saying they hadn’t been given a second appointment or heard anything further. At the same time, Doroshin’s team ghosted on hosting a testing clinic in the Fairhill neighborhood, one of Philly’s poorest. “The Department of Public Health asked us to set up a mass vaccination clinic this week,” Victoria Milano, Doroshin’s site manager, told the community leader who was relying on the site’s testing capabilities. “Because of this, it will not be feasible to continue testing.”

Doroshin had hired his brother, Sergei, and a few of the college buddies he’d worked on the 3D‑printed masks with to help him handle the vaccination business, which Doroshin has variously claimed he funded with a $250,000 loan from a family friend or with profits he made by investing in cryptocurrencies. When details of the team’s fratty behavior came to the surface, some were pretty unambiguous: On his public Venmo feed, in between requests captioned “pfc payment,” Doroshin listed payments labeled “tits,” “boobs,” and “strippers n hoes.”

Behind the scenes, things had started to fall apart for Doroshin. After taking Philly Fighting Covid for-profit, he’d updated its website but left off a privacy policy. When reporters at local news outlet WHYY asked why, Doroshin added a line to the site that suggested people who signed up with sensitive medical information for their testing clinics could have their data sold. At the same time, one volunteer nurse at PFC’s vaccine clinic reported seeing Doroshin bringing shots home with him to administer to his friends, which several people reported to WHYY, saying they saw him bragging about it on Snapchat, where images disappear shortly after they’re read.

Only three weeks after his first interview with Gosk, the Today show reporter, Doroshin sat for a much more hostile follow-up. He acknowledged taking the doses but maintained that his team had called around to see if anyone wanted them first. Ultimately, he chose to give the vaccine to himself and his friends because “doses were about to expire.” When Gosk pressed Doroshin on the question, “Are you qualified to administer the vaccine?” Doroshin sheepishly responded no.

Within days the city closed Doroshin’s clinic and terminated PFC’s contract. At his press conference in January, Doroshin blamed Farley, the health commissioner. “I have yet to find out why they cut ties, but I strongly believe there should be an investigation,” he said. Doroshin emphasized several times that he believed Farley should resign. A few days after the fallout, Johnson, the deputy health commissioner who’d championed Doroshin’s effort, resigned. Farley did the same several months later after he admitted to an unrelated failure: He’d mishandled the remains of the victims of the 1985 MOVE bombing, during which the city of Philadelphia bombed a house belonging to Black activists, killing five children and six adults and allowing a subsequent fire to destroy 61 homes.

Doroshin’s bro-y clown show might have been amusing if it hadn’t distracted Philly from hiring real experts. While he received the go-ahead to start his first vaccination clinic, Ala Stanford, a veteran doctor in the city, was left waiting for her own approval. Stanford was also running testing clinics through her Black Doctors Consortium and had been on the same vaccination advisory committee as Doroshin. Her group received approval to begin giving out shots at Temple University shortly after the city terminated its contract with the grad student. “She’s been a doctor longer than he’s been a person,” Ajamu notes. “Dr. Stanford is so accomplished and has so many accolades and has a history of mobilizing health events. As a Black queer person, I feel like mediocre White folks get put over Black folks all the time. This was just a case study in that.”

Back in January, Doroshin offered his best defense for his debacle to date, which still wasn’t very good. “We’re a bunch of kids,” he told the New York Times. “I didn’t know anything about legal structure before this. I didn’t care. I’m not a lawyer, I’m a nerd. People are trying to make me out to be this nefarious thing. I’m like, ‘Dude, I didn’t know all the rules of a nonprofit organization until I did this.’ ”

Until May the last anyone heard from the former grad student—his LinkedIn page notwithstanding, Drexel University says he’s no longer enrolled there—was at the end of February, when he emailed what he called an apology to Philly Fighting Covid’s original donors. It was less an apology than a screed against his haters. After thanking his donors for “believing” in PFC, he wrote, “But first, there is an apology. There were some minor administrative decisions that were the fodder that was needed for competitors and other groups that did not share our interests to shut us down and personally discredit me and my team.” He said he would shift the operation’s focus to paying its debts and “recovering the good of our names.” He ended the email with the line “Thank you for your concern and your support,” suggesting unpersuasively that there had been some outpouring of interest in his well-being rather than his comeuppance.

In the meantime, though, Philly has largely recovered from its early stumbles. In March the city reopened the convention center as a mass vaccination site, now in partnership with the Federal Emergency Management Agency. Anyone who had received a first dose through PFC could also get a second dose there. By June more than 740,000 people, almost two-thirds of the city’s adult population, had been fully vaccinated. (It didn’t hurt that many local eateries and drinkeries were offering people with vaccination cards a free doughnut or beer.)

The Black Doctors Consortium was still running clinics aimed at disenfranchised people, now called Philly Vax-Jawn events, and tried to overcome vaccine resistance by offering lottery winnings of $10,000 to a random person receiving a second shot. Covid restrictions had been lifted entirely, and people were out and about in the sunny city, walking their dogs, drinking beers, and rooting for flailing sports teams—all of them proud, once again, to be here.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.