California Is Stuck Fighting Climate Change With a Bankrupt, Distrusted Company

PG&E Fanned the Flames That Made California Burn

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Laine Mason arrived at work on Nov. 8 expecting a busy day: Strong winds were forecast, which meant falling branches and toppled trees, and with them the possibility of downed power lines. Mason, who lives in the Northern California town of Corning, works for Pacific Gas & Electric Co. as what’s known as a “troubleman.” A 50-year-old former logger, he drives a robin’s-egg-blue PG&E bucket truck and wields a chainsaw and a 6-foot-long fiberglass hot cutter that can sever live power lines. In his words, “If you call PG&E and say, ‘Hey, my lights are out,’ they send me out to figure out what’s going on.”

That morning, Mason and two fellow troublemen were waiting for assignments in the company’s yard in Chico. At around 6:45, the others were sent out to deal with an outage on nearby Flea Mountain. A little later, Mason’s boss called and told him to head to Paradise, a town in the Sierra Nevada foothills, where another of his co-workers needed help. Mason could already see smoke, and on the road he passed a steady stream of cars headed the other way. In the time it took to drive 15 miles, a small blaze that had been spotted a few miles from Paradise had exploded into a wind-whipped, galloping monster. He was just outside town when the inferno arrived. “I saw the treetops start swirling around,” Mason says, “and within five minutes it was like midnight—the fire was there, the smoke was there.”

Mason worked all that day in Paradise, clearing fallen poles and lines. For a while he partnered with a team from the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, or Cal Fire, opening paths through the downed debris so the firefighters could go house to house urging holdouts to evacuate. He stayed on the south side of town, where the blaze was less intense, moving downhill when it edged closer, watching houses around him combust and smolder. His co-worker, he later discovered, had been trapped in the gridlock created by panicked evacuees on the north side and had survived by moving to the center of a large parking lot. Mason worked until 10 that night, went to Chico to grab a bite, then drove back up. When he finally left, he’d been on the clock for more than 36 hours.

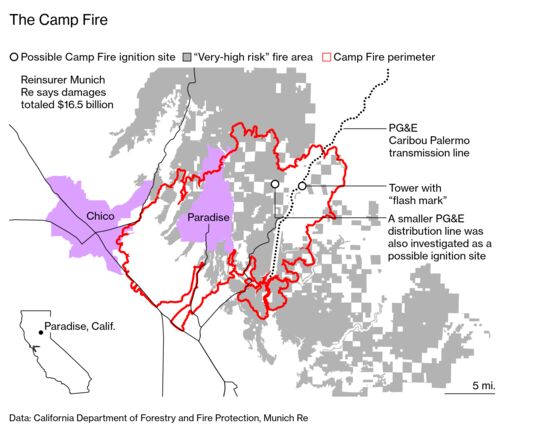

His cleanup assignment in Paradise lasted two and a half more weeks. For the most part, people were happy and grateful to see him. A few, though, seeing his truck, would yell profanities and flip him off. A PG&E mechanic he knew was spit on at a fast-food place. Others got called murderers. Mason knew why: The day the fire started, PG&E had filed a report with its regulator, the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC), raising the possibility that the utility itself had caused the inferno—at 6:15 that morning there had been an outage on a transmission line on the hillside east of Paradise where the fire was first reported. Later examination showed an insulator and jumper wire that had broken loose from the tower, and a “flash mark” where the damaged equipment, swinging free, could have created an electrical arc, sending sparks into the parched vegetation below. In a follow-up filing, the utility mentioned a second outage a few miles away from the first and a half-hour later—the Flea Mountain outage. It could have been a second ignition point.

The Camp Fire, as it was named, proved the deadliest and most damaging blaze in California history—85 people were killed, most of them in Paradise, and 18,800 buildings were destroyed. Cal Fire won’t conclude its investigation into the cause for months, possibly years, but the realization that PG&E’s equipment might be the culprit led in short order to a collapse in the utility’s stock price, the resignation of its chief executive officer, and, on Jan. 29, a declaration of Chapter 11 bankruptcy. On Feb. 28 the company reported to the Securities and Exchange Commission that it is “probable” PG&E equipment will be found to have started the Camp Fire. Survivors of the disaster, along with insurers and the town of Paradise, have already brought more than 40 lawsuits against PG&E, adding to 700 suits already on the books for its role in deadly fires that ravaged the state’s wine country in 2017. The plaintiffs’ attorneys—and angry protesters at the utility’s regulatory hearings and its San Francisco headquarters—portray a company whose negligence led to death and disaster. PG&E’s defense is that, for reasons beyond its control, it’s become impossible to prevent these catastrophic fires, no matter how careful the company is.

In the coming months, judges, juries, regulators, and politicians, not to mention PG&E’s millions of customers, will be parsing the company’s culpability. The bankruptcy is an early test of the state’s new governor, Gavin Newsom. But this isn’t just a California story. It’s also a multibillion-dollar case study for a set of once-abstract questions about corporate responsibility, societal risk, and climate change. California’s political leaders have long seen the power grid as a vital tool for reducing carbon emissions to curb global warming. What’s become clear is that the grid is also dangerously vulnerable to the already palpable effects of climate change. The future that climate scientists have been warning of has arrived, and the system in place to power our wired world wasn’t built to withstand it.

The company that would become PG&E was founded in 1852, when gas was used not for heat but for light. A series of mergers moved the growing company into the new electricity business as well, culminating in the 1905 union of California Gas & Electric and San Francisco Gas & Electric. The resulting utility was a hydropower pioneer, generating electricity from the snow-fed rivers of the Sierra Nevada and bringing it down to San Francisco and the Sacramento Valley’s fertile farmland. In the years after World War II, the utility built a 500-mile pipeline to bring in natural gas from Texas. Like other utilities, PG&E was long seen as a reliable widows-and-orphans investment, a government-regulated monopoly whose dividend was supplied by the payments on gas and electricity bills.

In the mid-1990s, to combat high electricity prices, the California Legislature and the CPUC decided to break up the state’s three big utilities. PG&E, Southern California Edison, and San Diego Gas & Electric were required to sell most of their power plants to independent electricity providers, then begin buying electricity from these suppliers on a specially created exchange. They were also forbidden, for a few years, from raising the rates they charged their customers.

Then, in the summer of 2000, a combination of factors—among them a heat wave that caused air-conditioning usage to spike and a drought in the hydropower-reliant neighboring states from which California usually bought some of its power—created an electricity shortage, driving wholesale prices up. Thanks in part to the poor design of the state’s new electricity market, suppliers discovered they could make more money by withholding power, exacerbating the shortage and further increasing wholesale prices—energy traders at the soon-to-be notorious (and defunct) Enron Corp. proved particularly creative and unscrupulous in this regard. With retail prices capped, utilities began hemorrhaging money. There were statewide rolling blackouts, and the mess helped lead to an unprecedented recall of the state’s governor, Gray Davis, and the election of Arnold Schwarzenegger. PG&E declared bankruptcy in April 2001, claiming debts of $18.4 billion—money its customers helped pay off when, as part of its reorganization, the company was allowed to raise its rates.

Over the past decade, the utility has been shadowed by deadlier disasters. On Christmas Eve 2008, a PG&E gas line explosion outside Sacramento killed a man and injured five members of his family. The evening of Sept. 9, 2010, another PG&E pipeline exploded in San Bruno, 12 miles south of San Francisco. The blast sent a 28-foot section of pipe skyward, and the resulting fireball destroyed 38 homes and killed eight people. Gas continued to flow out of the crater and feed the fire for an hour and a half, until two off-duty PG&E mechanics who’d heard about it on the news arrived and manually closed the valves.

An investigation into the explosion by the National Transportation Safety Board, whose remit includes accidents involving the transport of hazardous materials, was damning. PG&E’s protocols for ensuring the mechanical integrity of its pipelines, the agency’s report read, were “deficient and ineffective”—the pipe that blew up had been misclassified for decades and, as a result, only cursorily inspected—as was its fumbling response to the disaster. The CPUC imposed a record $1.6 billion penalty, and in 2016 the jury in a federal criminal trial found PG&E guilty of six felony counts of violating pipeline safety regulations and obstructing the NTSB investigation. The judge fined the utility $3 million and sentenced it to probation, complete with community service for its executives and a requirement to pay for national media ads to “publicize its criminal conduct.” A monitor was assigned specifically to oversee the safety of the company’s gas system.

In the wake of the San Bruno fire, PG&E hired a new CEO, Tony Earley, a lawyer and onetime nuclear submarine officer who’d previously run the Detroit-based utility DTE Energy Co. PG&E tested and replaced hundreds of miles of pipelines, opened a gas-safety operation center, and installed more than 230 automatic or remote-controlled valves throughout its gas transmission network so workers wouldn’t need to manually shut off the flow in an emergency. The gas business, long a stepchild to the much larger electricity division, got its own dedicated management team.

Earley’s tenure coincided with a push by California’s government to deploy the state’s utilities to meet ambitious green energy goals. In 2011, California passed a law mandating that a third of its energy come from renewable sources by 2020. PG&E signed contracts to buy power from a giant wind farm at Altamont Pass and solar arrays in the Mojave Desert—and, increasingly, from the rooftop panels Californians were installing on their homes. It hit its renewables target three years early, in 2017 (as did Southern California Edison and San Diego Gas & Electric).

That year, Earley stepped aside for Geisha Williams, who as PG&E’s president had overseen the politically fraught process of decommissioning the company’s Diablo Canyon nuclear power plant. (It’s expected to be retired in 2025.) A daughter of Cuban dissidents, Williams became the first Latina to head a Fortune 500 corporation. “We at PG&E are deeply committed to the California vision of a sustainable energy future,” she announced from a conference stage in early 2018. “We see the electric grid as a climate solutions platform that offers the scale to support this transformation.”

Californians haven’t forgotten the San Bruno explosion and the lapses it revealed, however. “They have a rap sheet much longer than any other utility,” says Mindy Spatt, a spokeswoman for The Utility Reform Network (TURN), a ratepayer group. “I mean, the pattern is clearly there. It’s negligence, negligence, negligence, again and again.”

California has always burned. Flames drive its ecosystem; coastal chaparral and mountain pine alike depend on summer wildfires to clear the open spaces where they thrive. But in recent years, fires have grown more frequent—and more destructive. According to Cal Fire, 12 of the largest 15 fires in state history have occurred since 2000. It’s impossible to trace this change to any one cause. For decades, the owners and overseers of American forests suppressed the regular burns that clear out underbrush, ensuring that when fires do occur they have more fuel. A punishing drought and a bark beetle infestation in recent years have combined to leave hillsides dense with dead, dry trees. And more and more people, priced out of the state’s metropolises, are building homes in what was formerly wild land, in the path of blazes that once killed only wildlife.

In addition to these factors, and often exacerbating them, is climate change. Warmer winters have helped bark beetle populations explode, and hotter summer air sucks more moisture out of vegetation, priming it for combustion. There’s also growing evidence that warming is shifting California’s precipitation patterns, delaying the autumn rains that once brought a reliable end to fire season. “Part of it is the temperature,” says Daniel Swain, a climate scientist at the University of California at Los Angeles and the National Center for Atmospheric Research, “but it’s also a change in the seasonality of the rain.”

The past two years have been especially bad. The 2017 wine country fires burned more than 245,000 acres and killed 44 people; last year, even before the Camp Fire and the devastating Woolsey Fire in Southern California, an area about the size of Delaware had been scorched. Power lines are far from the only culprits—wildfires are more commonly sparked by untended campfires, cigarette butts, or the sparks thrown from the wheel rims of flat tires. Nevertheless, Cal Fire investigators have found PG&E equipment responsible for at least 17 of the 21 major 2017 fires and referred 12 for possible criminal prosecution. The utility’s critics charge that, as with its gas lines, PG&E failed to properly inspect and maintain its infrastructure. On Feb. 27, the Wall Street Journal reported that PG&E had for years been delaying planned safety upgrades along the nearly century-old transmission line where the first Paradise outage occurred. The many plaintiffs suing the company accuse it of habitually failing to protect its lines by trimming dead trees and other vegetation.

In response, PG&E spokeswoman Lynsey Paulo pointed out in an email that the utility spent $2.3 billion on vegetation management from 2013 to 2018, patrols every mile of its 100,000 miles of overhead wires at least once a year, and prunes or removes 1.4 million trees annually. Among the employees and contractors tasked with this, she notes, “more than 300 have International Society of Arboriculture certifications.”

Compounding PG&E’s problem, however, is California law, which allows the company to be found liable even if it did nothing wrong, under what’s known as “inverse condemnation.” This concept grows out of the more familiar notion of eminent domain: If your home happens to be where the state plans to build a highway, the state can condemn it, pay you just compensation, and take it, all in the name of the public good. Now imagine the inverse: The state, or a utility acting on its behalf, irreparably damages your home in the process of performing a public purpose (such as providing everyone electric power). Your property has effectively been condemned, and you’re owed just compensation, whether or not anybody has been negligent. “If this is for a public purpose, then you shouldn’t put all of the burden on this one landowner,” says Shelley Ross Saxer, a Pepperdine University law professor. That’s the argument, at least, and California’s courts have found it convincing.

Despite intense lobbying by PG&E and the support of Newsom’s predecessor, Jerry Brown, the California Legislature has refused to pass laws that would weaken inverse condemnation. Last September, Brown did sign a measure that would allow PG&E to recoup the costs of its 2017 wildfire lawsuits by issuing bonds backed by customer bills, as long as the CPUC found that the utility hadn’t been negligent. That law, however, doesn’t cover the 2018 fires—legislators were reluctant to give utilities a free pass going forward.

Only three weeks after the Camp Fire was finally under control, the CPUC released a report accusing PG&E of falsifying pipeline location records from 2012 to 2017, increasing the odds that underground construction crews might accidentally crack the pipes. The news exhausted any sympathy that remained in the state legislature for the utility. On Jan. 30, William Alsup, the federal judge overseeing PG&E’s probation, ruled the utility had violated the terms of its supervision. He proposed that, as part of its probation, the company reinspect its entire grid, remove or trim all trees that could fall on its lines, and begin aggressively shutting off electricity to at-risk areas when conditions are ripe for fires, no matter the inconvenience to customers or the cost to the company.

In court filings, PG&E pushed back, saying those measures could cost as much as $150 billion. But changes were already under way. In mid-January, Williams stepped down. A little more than two weeks later, PG&E filed for bankruptcy protection, citing $30 billion in potential fire lawsuit liabilities (its Feb. 28 SEC filing took a $10.5 billion charge against earnings for Camp Fire-related lawsuits alone) and an insurance policy that would cover only $2.2 billion of that. On Feb. 11 the company announced that at least half of its board was leaving.

Even nonbankrupt utilities are rarely the masters of their fate. PG&E has always had to answer to state politicians and the CPUC. More recently, there’s Judge Alsup. Now a bankruptcy judge will oversee the utility’s finances. Already there’s been tension among the company’s different overlords, reflecting the different goals PG&E has been assigned. At issue are the utility’s contracts with solar and wind providers. The deals helped it surpass its green energy mandates, and they also boosted the then-nascent renewables industry, locking in prices, often for decades, as a guarantee of future income. With advances in technology, however, the cost per kilowatt of wind and solar has dropped precipitously: Were PG&E buying its renewable energy at today’s market rates, it could save about $1.1 billion total, estimates BloombergNEF.

A bankruptcy judge interested primarily in putting PG&E on sounder financial footing might allow it to break those contracts. The victims in that case would be not only PG&E’s renewables suppliers, but also all green energy companies, which would likely find investors leery of being similarly kneecapped by a bankruptcy judge. Climate change, like a science fiction villain with a time machine, would have managed to undermine today’s efforts to combat its future effects.

Meanwhile, the June start of the 2019 fire season grows closer. PG&E is stepping up tree trimming in high-risk areas, increasing inspections of power lines, and installing more sensors and cameras to detect shorts and spot fires once they start. The utility also plans to replace wooden poles with fire-resistant composite ones, install insulated power lines, and expand its network of weather stations. All of that costs money, of course, money that can’t go toward subsidizing clean energy (a law passed in September requires California utilities to be 50 percent green by 2026 and entirely carbon-free by 2045) or reimbursing wildfire victims. Days before filing for bankruptcy, PG&E told a judge it could no longer afford settlement payments it owed victims of a 2015 fire traced to its equipment.And it’s pledged to be more aggressive in cutting off power to parts of its grid when the fire risk spikes, meaning preemptive blackouts may become a fact of life during the state’s lengthening fire season.

PG&E has been understandably eager to stress the role climate change plays in California’s fire-plagued “new normal.” Williams, before her departure, repeatedly emphasized the link. To the utility’s many critics, this sounds like a tactic to minimize its own accountability. “PG&E blames Northern California’s wildfires on climate change,” says California State Senator Jerry Hill, a longtime critic whose district includes San Bruno. “But that didn’t ignite the fires. PG&E’s equipment did.” On Feb. 6 another PG&E gas main exploded in San Francisco, igniting a fire that burned five buildings. It is said that generals always fight the last war, but PG&E seems unable to do even that.

In response to criticism such as Hill’s, the company sent a statement acknowledging that “while we have made progress, we have more work to do. … PG&E is committed to working cooperatively with regulators, policymakers, and other stakeholders to continue to provide PG&E customers the safe gas and electric services they expect and need.” The company declined to make any executives available for this story.

To the extent that California’s heightened flammability is related to climate change, it’s not just PG&E’s problem. A Feb. 19 report from S&P Global found it “entirely possible” that the 2019 fire season would force one of California’s other investor-owned utilities into bankruptcy. Because of rising temperatures and the ways they’ve begun to perturb the dynamics of Earth’s atmosphere, extreme weather outliers—fire seasons that stretch through November, polar vortexes, 100-year floods—are becoming commonplace. Replacing wooden posts will probably help prevent wildfires, but it’s not only physical structures that need updating. Electricity infrastructure safety regulations are products of a time when fires were less common and less disastrous. The job of inspecting power lines, for example, is largely left up to the utilities themselves. “The way we do grid safety is not the way we do food safety or airline safety,” says Severin Borenstein, director of the Energy Institute at the Haas School of Business at the University of California at Berkeley. He argues that some sort of change is inevitable: “It’s clear that when we have these really serious risks, we move to a different model.” That model entails, at a minimum, oversight bodies with the money and manpower to carry out their own inspections, as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and the Federal Aviation Administration do.

Investor-owned utilities such as PG&E have always been odd beasts: private companies providing public services. Much of the argument so far has been over who will have to shoulder the costs of hardening the grid and compensating fire victims. Should it be the shareholders or ratepayers? Nobody wants to bail out a negligent company. On the other hand, it’s foolish to think that all of us won’t bear the costs of adjusting to and, if possible, mitigating climate change. Those costs could take the form of bigger electricity bills. They could mean higher insurance premiums for those who live in the widening path of floods and fires—an expense often passed along to fellow policyholders and taxpayers by public insurance programs. (California legislators are discussing a state-run wildfire insurance fund modeled on one in Florida for hurricanes.) In a world ruled by economist-kings, the costs might take the form of a carbon tax.

“This is going to be happening everywhere,” says Pepperdine’s Saxer. “It’s not just the fires, it’s the floods with sea level rise. We just keep tossing back and forth who’s going to pay for it, but we’re all going to have to pay for it. It’s just a question of how.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Ferrara at dferrara5@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.